In a no holds barred interview with critic, translator and former publisher Chandana Dutta, Dibyajyoti Sarma of Delhi-based Red River spills the beans about poetry publishing in India, and what it means to be a small publisher.

Chandana Dutta: Poetry conventionally has been seen as a difficult genre to publish in. But with the growing number of publishers dedicated exclusively to poetry – although this is still a small number, and we hope it will expand constantly – would you consider that there is a real change in the market for poetry in India today? I’m using the word market deliberately to distinguish between those who enjoy reading poetry but may not buy poetry books and those who would spend money on buying poetry books. What is the economics of poetry publishing in India today?

Dibyajyoti Sarma: There are two questions here—the market for poetry, and the economics of poetry publishing. At some level, both are related, yet, we need to tackle them individually.

The answer to your first question would be—maybe—perhaps. In the last decade or so, social media has profoundly changed the way we read and appreciate poetry. Now, more and more people are reading poetry online, and in turn, are sharing their own poetry online. So, online is a vibrant place for poetry. So, for the majority of readers, the question of buying a book doesn’t arise as they are reading the poems online, unless it’s a “name” poet—you know who they are. So, as an average poet, who are your readers? First, your friends, then maybe a couple of people who genuinely like your poetry. It will depend on your skill in social networking and your reach.

Please note that we are not against social media. Social media, in fact, has helped Red River find more visibility. But it doesn’t necessarily help sell books.

The situation is not as grim as it sounds. Poetry traditionally has fewer buyers. It’s a fact and we cannot change it. Perhaps there are around 5,000 people in India who regularly buy poetry books in English. At Red River, our goal is to reach at least 200 of them. If we can sell 200 copies of our titles, we are happy. It doesn’t always happen.

My observation is, there are readers of poetry, and there are people who are willing to buy poetry books as well, but they wouldn’t buy them from a bookstore, or from an online marketplace. If you take the book to them, in a literary event, for example, and if the book is priced lower, and if the author is around to sign the copy, there are chances that readers will pick up a copy. But as a small publisher, we cannot be travelling to such events.

To answer your next question, the above-mentioned aspects help make the economics of poetry publishing easy for us. Since our goal is to sell just 200 copies, we print just 200 copies for the first run, unlike the traditional 11,000 copies of a fiction title. And since people don’t buy poetry books in bookshops, we don’t usually stock our books in bookstores, and sell them exclusively on Amazon. There are even fewer avenues to publish reviews of poetry books. So, we don’t spend much on review copies and other promotions. All the promotions we do happens online. In this regard, we are following the existing paradigm of poetry in India, and we complete the circle.

That said, I must thank a couple of bookstores in cities like Delhi, Bengaluru, Manipur, Goa, who bravely stock our books, and some have even managed to sell them.

Chandana Dutta: As a publisher what is it that you are looking for from poetry manuscripts that are submitted to you? What specifically is your method of selection from the many that you must be receiving? Do you respond differently to the poetry that you work with when you are in the role of a publisher from let’s say when you are simply reading another poet as a poet, not a publisher who has the market in his line of vision too?

Dibyajyoti Sarma: To answer your second question first, nowadays, I honestly find it difficult to read a poetry book by another publisher without thinking about how I would have edited and designed the book. Sometimes, I feel I could have done it better, and sometimes I am simply jealous because someone has done such a fantastic job which I wished I could.

Regarding manuscripts, I am not sure there is a guideline for us. We have published all kinds of books. While selecting a manuscript, we look for two things—heart, and the poet’s willingness to work with us during the editing process. Not every manuscript has to be great, but they have to be honest and rooted in the poet’s own experience and emotion— “the heart”. As I tell my poets, we need a good skeleton of a book, and if the poet is willing, we are ready to help the poet to add flesh to it. Since we are not going to have a bestselling book anyway, we never worry about how we are going to sell the book. Our concern is to make the book the best version of the book it can be.

Chandana Dutta: How has the poetry scene grown and changed over the years in India, in English as well as in the many languages across the country? How has it evolved in terms of language, style, form, content, etc.? In addition, since you also publish translations of poetry, how do you see the pan-Indian poetry scenario?

Dibyajyoti Sarma: Oh, we, the readers of English poetry, are often unaware of the wonderful experimentation happening in poetry in Indian languages, in terms of style, content and concern. In the early 20th century, most Indian language poetry was inspired by the modernist movement. In the last 50 years, however, they have evolved and come to their own. The Indian language poets read English, and European poets but write about their own concerns. There is a sense of urgency in using regional dialects and regional concerns in their poetry than is possible in English.

This is why we are so keen on publishing poetry in translation. But, it’s not easy. Indian languages have different cadences than English, so it’s not always easy to translate from Indian languages. We still do not have many experienced translators who can confidently bridge this gap. For us, the key to a good translation is—one, the text must read idiomatically English, and two, it must retain the essence of the source language. It’s a tough balancing act.

Talking about English poetry, I have observed that most Indian poets are keen readers of foreign poets, even in translation. But unfortunately, they do not share the same enthusiasm as far as their peers based in India are concerned. It’s ironic—they write and publish in India, but wouldn’t read other Indian poets. There are so many poets in India—if only 25% of them purchased poetry books published by their fellow poets, each book would be a bestseller.

And yes, I deliberately did not answer your question about style and form.

Chandana Dutta: It’s a very welcome step that poets in India have taken to publishing poetry themselves because they are perhaps the best suited to understand the content and the production. Poet-publishers in India today refer to their vocation as a movement. Hemant Divate writes of it as such, and he seems to be right. As a poet-publisher yourself where do you think we stand within the country and globally?

Dibyajyoti Sarma: It’s interesting that you mentioned Hemant Divate. I truly believe that without Poetrywala, Red River would never have come into existence. Poetrywala proved that it’s possible to sustain a dedicated poetry publishing venture in India, and we and several others followed suit. All of us have different visions and we publish widely different books, but the core, I believe, is the same—we believe in poetry.

And, let’s not kid ourselves, except for a select few poets, Indian poetry is largely unknown on the global stage. It’s not because we don’t have good poets or good publishers, it’s because we have failed to reach global audiences because that is a whole different ballgame. That’s why I have such respect for Kolkata-based Seagull Books. But things are changing. Nowadays, I see so many young poets being featured in international journals and it’s a welcome change.

Chandana Dutta: As a poet what defines poetry for you? This may seem like a tautology but, for you, personally, what sets a poem or one poet apart from others? Do you believe that all poetry, all poetic attempts, are essentially personal engagements and that alone justifies all of it?

Dibyajyoti Sarma: Yes. And no. Poetry is essentially personal. It has to be. It’s the genesis of poetry. But it’s not enough. It’s also important how you say it—craft is equally essential. It’s like learning a language. Each of us has different levels of vocabulary, different accents, and different cadences—that’s the craft.

Personally, for me, I think, I write Assamese poetry in English. Apart from the language, my aesthetics is influenced by the Assamese poets that I read growing up, those who inspired me to write poetry. So, it’s a vicious cycle. Unlike other poets with bilingual backgrounds, somehow, I am not interested in the function of language in poetry. I am old school. For me, poetry must tell a story. It must stir emotions. It must transcend personal for universal.

Chandana Dutta: Is there a strong supportive network of poets and poetry publishers today, one that can ease the lows a little and as a community helps to move ahead with more determination?

Dibyajyoti Sarma: Yes. I have been lucky to find help from some of the poets I have published, who have happily edited some of our titles, who have given me money to publish, and has helped with other measures. But I try not to look a gift horse in the mouth. So, I am a little apprehensive about seeking their help constantly, as I cannot always pay them for their work, and paying for the work is a must. So, I usually handle everything myself—from commissioning to editing, to designing, to marketing. It’s not an ideal situation, but where is the money?

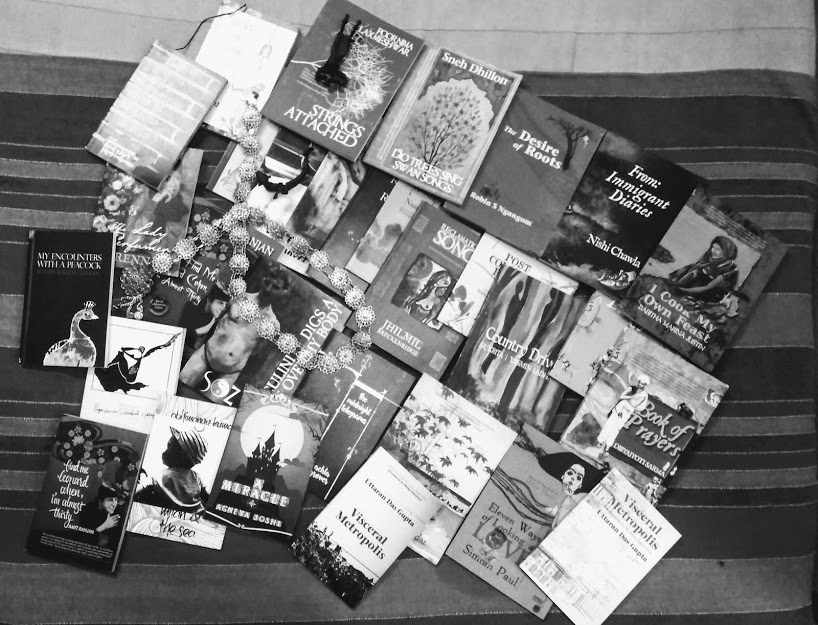

When I started Red River, I was hoping to build a platform that could nurture a community of poets. I am not that idealist anymore, but I still believe there is a sense of community among the poets I have published—all united by the Red River experience. Some years ago, in an interview I said, in every Red River title I publish, I put a part of my soul into it. Today, I have become more pragmatic, but yes, I am happy to be a part of these numerous adventures undertaken by our poets. Once the book reaches the author, the first thing I ask: ‘Are you happy?’. If the author is happy, my work is done.

I never ask my poets to buy our titles, but they often do, and I am happy to see that. That’s support!

At Red River, we have largely worked with first-time poets, and I enjoy editing debut collections. To use a metaphor, in the large world of literature and publishing, Red River is like a tiny primary school in a small village. Our students are talented and eager, and I, a mediocre teacher, try to help them to the best of my ability as they set out to join a bigger school in a big city. When they succeed, nobody is happier than I am. I take it personally. I hope they feel the same about me.

Chandana Dutta: How do you see yourself as a poet, your journey, your growth, difficulties you may have faced, influences, the support?

Dibyajyoti Sarma: I still find it difficult to call myself a poet. I am still learning how to be a poet. That’s why I am hiding behind the role of a publisher. Red River started because I wanted to publish my own book of poems and had already decided that no other publisher would be interested. I still find it difficult to promote my own work. But I think I am a good translator, thanks to my work as an editor.

It’s been five years since Red River become Red River (earlier it was called iwriteimprint, which I started on a whim), and it has been an exciting journey. As psychology goes, I had a massive fear of failure, which prevented me from doing anything substantial for a long time. So, when I finally started Red River (after mulling over it for four years, and without any capital), it was a venture to be a failure. So, there was no plan. I made things up as I went along. Because I am ready to shut shop any day, every day. I find the idea quite empowering. It’s not a livelihood for me (and I know I cannot make it a livelihood; I work full-time in a b2b magazine). So, I can call it quits anytime.

You know, if you look at the history of independent poetry publishing in India, small presses do not last long. So, I am happy that we lasted at least five years. Even now, the thought comes to mind, I must fold Red River and move on. Then I find an exciting manuscript in my inbox, and the journey continues. The future is uncertain anyway.

Chandana Dutta: As the founder-director of Red River that has dedicated itself to publishing poetry, what has your journey been like? From the huge lineup of poets in your catalogue, Red River’s creative journey seems like a success story. But how about the market, the finances involved, the returns, and the growth that you visualize for this outfit as a successful, profitable, and self-sustaining unit?

Dibyajyoti Sarma: Some of these I have already answered.

Yes, I dream of making Red River self-sustaining. But not sure, it will ever happen. I know, I am not a business. I come from a lower-middle-class family in Assam. Two of my family members tried to start their own businesses and failed miserably. So, I refuse to be a businessman. My only concern is finding the printing cost for the books I publish, and the cost has skyrocketed. Other things fall in place.

Bookselling is a volume game. On the higher side, on average, we sell two hundred copies. And our titles are priced low, and our distributor gives us the 50% of the cover price on books sold, after deducting the amount spent on transportation. On the other side, our printing cost is higher because our print runs are small. So, the math for profit doesn’t add up.

I usually introduce Red River as an independent publisher, but honestly, the moniker doesn’t suit us. I think we are three rungs below an independent publisher. We are something of an anomaly and happily so. Finally, it’s about the product. Trust me, each Red River title is precious, published with love, care and sensitivity.

*

A nice interview answers coming from the heart

A nice interview answers coming from the heart