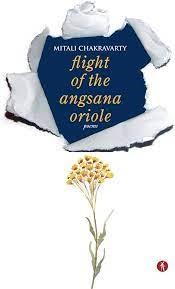

“Angsanas are flowers that bloom on tall trees. They are a common site in Singapore, where I stay. Golden orioles are almost the same yellow as angsanas. The orioles flying out of the angsanas are a magical sight – almost like a flower that takes flight,” writes Mitali Chakravarty introducing her debut collection of poems.

A yellow bird emerging out of a yellow flower to take flight in the endless sky is an image as spectacular as it is precarious, as extraordinary as it is commonplace, and as material as it is mystical. There is a profundity in its suggestions of liberty and possibility, and in its rich shade of yellow is an enticing hopefulness and a sprightly sense of spring that speaks volumes for the world and worldview that watermark this book.

For readers who are acquainted with Mitali’s work at and for Borderless Journal of which she is the Founding Editor, the seventy-two poems in Flight of the Angsana Oriole will be seen to emerge from ideas that run close to her soul and inspire almost all her work as editor and writer – humanity, brotherhood, borderlessness, nature and the nourishing art of love:

Love that grows

with age, with corona,

with cancer

…

Love that stays

… bonded forever by an invisible thread (‘Love’)

A dense lyricism suffused with an equally strong sense of angst permeates these poems that are, in many ways, about home. Here are diasporic journeys through dream and memory into a past that will never be recovered:

No longer will I be a daughter –

Just a plain little daughter (‘For My Father’)

They are, at the same time, about homemaking and the reconstruction of the self in new lands. In Mitali’s case, home, experienced through a wide globe-trotting across cultures and landscapes, often fuses into the essential realization of the oneness of mankind and in the search of “the inner wiring/ of the human soul, the human spirit,/ that forever soars beyond hate, beyond/ personal space, beyond land divided/ by boundaries, into an eternity of freedom, where the infinite sky stretches….” (‘Arbitrary’)

Evoking images of Lalon and Tagore, Mitali finds in the universal brotherhood of Man both belonging and healing — “the sky that unites/ like an awning”. (‘Independence Days’) In poem after poem, she challenges the divisive values of a society that aligns itself under countless banners only to distinguish and separate — “the ruthless/ rodents masked with human/ faces screaming ‘Divide’” (‘Death of Lalon’)

The empathetic memory of global atrocities against humanity insistently haunts the subconscious of these poems as they strive to delineate everyday emotions of safety, love, hunger, longing, and companionship in the context of such catastrophes, humanizing suffering by converting it from statistical to emotive data. Whether it is war, genocide or partition, the stark narrative contrast between the personal and the political steadily draws Mitali’s attention. Against the rhetoric of ideologies and diplomats, she repeatedly exhorts us to analyse the human costs of suffering:

This loss of homes.

Rohingyas.

Ukrainians

Afghans

Palastine-Israel.

People are born in camps

in no man’s land. (‘Weaponising Words’)

Side by side with the theme of violence, there blossoms in these poems the firm insistence on love and peace. Love, in Mitali’s poems, assumes a variety of forms. There is the daughter’s love for her parents, the mother’s love for her children, the nature-lover’s attention to every detail in her workaday world, the humanist’s love for mankind, and the mystic’s love for God. What is remarkable is how these various versions of love co-exist and converse with each other to create a collage of not just the poet’s life but of life as a whole that draws sustenance from all its relationships — “Which/ came first – the Universe/ or man, woman and child/ and our urges to equalise? ” (‘Should I be a Tree?’)

In the family poems, in particular, in this collection, one comes across an aching metaphysics that seeks to make sense of life by placing it in conjunction with death. Death holds profound fascination for Mitali as she examines it as a dissolution of the bonds of life, and a portal to a different world that is removed from life’s blatant injustices — “This is the end of her weary, worn life. ” (‘A Free Spirit’) Death, in these poems, is both severance and liberation, a cause of both lamentation and rejoicing. It is life’s ultimate end and more desirable, perhaps, given its mounting miseries – the deeply cherished “silence of the universe? ” (‘Tyrannosaurus Shen’)

Injustices against women bear a special place in Mitali’s circle of empathy as she documents, in several poems, socio-cultural practices that continue to victimize women down the ages – foeticide, infanticide, dowry-deaths, rape, domestic abuse In ‘Kali Rise’, for instance, she resurrects the image of a weeping Kali to seek civilisational retribution for generations of women’s suffering — “When with Kali-like blood curling cries will the woman fight/ Injustices, Murder and Abuse?” Here are also ecological poems that address global climate change and remind us of the ceaseless sufferings of the Earth-woman.

There are several poems in which the poet negotiates the issue of identity including her own. Identity is a narrative we construct for ourselves or that which is constructed by others and we learn to internalize and accept it sans questioning. Mitali repeatedly interrogates identity as a construct trying to dissociate it into its multiple layers of being and belonging. We are mostly multitudes, her poems insist, offering the universalist notion of the self as a manifestation of the world:

… – a dream –

a whiff of a drift,

a thing,

a creation,

a fantasy (‘Fantasy’)

There is a great deal of sensuousness about Mitali’s verse which is charged with romanticism in its appreciation of beauty as well as its exploration of existential angst. Her images are culled widely from the lush world of nature and her language, as it contours colours, shapes, and emotions, waxes lyrical and sensitive. There is a sense of devastation in this collection but also one of renewal; a sense of annihilation but never far from that of beginning anew. For all the pain and suffering that life has to offer, Mitali does not lose hope in the possibility of rejuvenation, and of a better world built collectively by human effort and vision.

The Flight of the Angsana Oriole, thus, articulates pertinent questions about our times, inviting us to cast off our weariness, pessimism, and apathy in order to make way for a world where children can smile and birds can take flight into the open sky. By conjuring a vision of sunshine and gold, and drawing attention to the metaphysics of life, the book offers a redemptive read for all who will choose to engage with it.

*

Mitali Chakravarty

Flight of the Angsana Oriole

Poetry

Hawakal Publishers, 2023

ISBN 9-788119-858170

Pp. 104 | Price 400

Add comment