There was a devastating piece of news, just over a month ago, about material remains of more than two hundred indigenous children found at a residential school at Kamloops in Canada. This discovery generated intense furore about the silence surrounding structural racism and child abuse, with many former students coming forward to recount horrific tales, accompanied by experiences of silencing, and the repression of what were entire generations of indigenous families. The racism quite apart, the heart quailed in outrage at the terrible sadness and pathos of hundreds of children, sacrificed within a system we call humane and just. Though not similarly abusive in that sense, it reminded me of an experience recounted by a friend. I remember even at the time she recounted it, of being brought up short in recognition of how children lead completely different lives from adults. And the sad part is that we forget this difference, as we grow older with the worries of the world overtaking us. The only residue of knowledge about the difference of childhood is a debilitating anxiety about the welfare of children.

My friend was member of her school choir. A good singer, she regularly participated in choir group activities, with her school being invited to present at important social functions, graced by diplomats and important dignitaries. Her school was affluent, and prominent among leftist Delhi circles. It had its own busses to ferry the choir to event venues. The busses always returned to school in time for students, already prepared with their school bags, to then clamber into their respective chartered busses waiting to take them home. That day, my friend, though she had left for an event with the choir group along with her school bag, realized that she had forgotten her tiffin box in the classroom desk. Running out of the bus that brought them back to school, she sprinted upstairs to her classroom to fetch her tiffin box. The original plan had been to run back downstairs in superfast speed, and get into the right chartered bus that would take her home with another hundred students who lived along the same route. For some reason, the schoolteacher allocated to her chartered bus was absent that day, and though the school bus driver remembered seeing her run inside the building, he got busy afterwards, and did not see her come downstairs again. The chartered bus driver did not take attendance in the absence of the schoolteacher, and simply left at the usual time, and by doing so, simply left my friend behind.

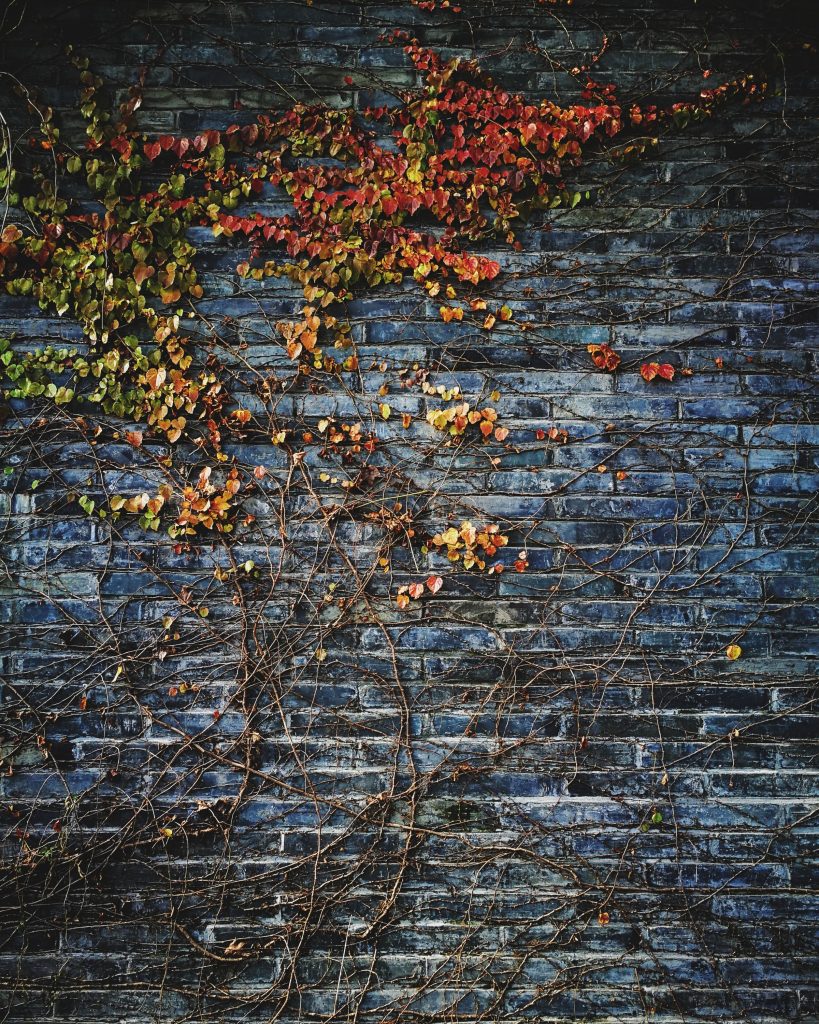

It is unclear why my friend did not come back downstairs either. She remembered reaching her classroom, but things became unclear after that. She remembered shutting the classroom door behind her and for some reason, bolting it at the top, for which she had to stand on an upturned dustbin. Retrieving her tiffin box had been easy. It was still half-full as she stowed it into her bag. And then for some reason, she just stood at the window, watching all the chartered busses leave. It had been a puzzling mystery—a childhood moment for which no adult explanation came to mind. Why had she locked the door? Why had she not run back to her chartered bus? Why had she not felt afraid of being left behind? It was unclear. She remembered to have quickly gone to the girl’s bathroom, that still had some girls loitering in front of the mirror, and then she had raced back into her classroom with the full intention of retrieving her tiffin box and running downstairs. But yet, things had changed as she entered the classroom. She could not tell what it was. It did not look like her usual classroom at all. The higgledy-piggledy desks and tables looked forlorn, as if from another universe. Never before had she noticed how lovely the late evening light looked, streaming into the room, and transforming it into incandescent radiance—a flame caught in clear light. She lingered. She felt like lingering, transfixed, and suspended in animation, relieved of all her responsibilities of homework and class tests that had taken place in the same room six hours back. Now, she felt like a pioneer who had rediscovered an unknown place, a secret—like the picture of Christopher Columbus setting foot in America in her textbook, welcomed by the Indians in the sketch with broad welcoming smiles.

My friend was eleven, and was going to be twelve in August. School had just opened after vacations in July. She was nearly twelve and was constantly told that she was a big girl now. She was uncertain what it really meant—there was an expectation embedded in the statement that tired her. But somehow, on that evening, she did not think of being a big girl, she did not feel afraid, and instead, just gave in to her natural curiosity. Huddling three or five stools together around a corner like a fortress, she sat silently behind it, inspecting the transformed room, the chart papers hanging on the walls with instructional diagrams, and the very architecture of the room, seemingly from another time, bathed in golden light. She dozed behind her mountain fortress. When she awoke, it must have been past seven thirty in the evening since the evening light was now gone. The tree outside was bustling with noisy birds, preparing for the night, and for the first time, the room looked different again. Robbed of its sunlit beauty, it now looked drab, grey, and cold, with no beauty to its dull, shabby interiors that had the feel of dirty cotton wool, or a crumpled cardboard.

My friend started feeling worried now. She checked the door, and tentatively put on the tube light. Instantly, the room was bathed in a surreal, buzzing neon glow that made the insides look even more forlorn, like a prison. It reminded her of darkened monsoon afternoons when the teachers, sometimes, switched on the tube lights. It was properly dark outside now, and a tiny bat flew into the room, attracted by the light. It circled in the light for a bit, and flew out, afraid of the whirring fan overhead. My friend, afraid by now, crouched low below the fortress, eating the slightly rancid contents of her tiffin box. She was unsure of what happened next. She slept a little more on the floor. When she awoke, she realized that she was in a timeless zone. She was deemed too young to have her own watch and her father had promised to buy her one, if she passed her 8th standard exam well. There was no clock in the classroom, and there was no question of a cell phone back in the 1980s.

She awoke however, not to silence, but to many noises and voices. The school, to her utter, and surprized horror, was hardly a silent place at night. She heard the hefty creak of swing chains, as they creaked when children played on them. She heard many running footsteps in the corridors outside, below, and above, with someone distantly yelling ‘catch’! There was the chattering of many childish voices, and the terror of its realization, made her heart feel as though it would stop. She began crying when someone playfully thumped the classroom door and ran away screaming with delighted laughter. Thanking her stars for locking the door, my friend, sobbing hysterically and dryly by now, crawled to the switchboard and switched off the tube light, afraid that the light would attract more attention from the playing children, who may want to include her in their dreadful night-time frolic. How would they find her body in the morning, she miserably wondered. Drowned in the pool? Hung from her tie? Or in the classroom itself, her head bashed in, her face covered with white chalk, as if in jest? The corridor outside briefly fell silent, as she turned off the light, as if registering that she had responded to the thumping on the door. She thought she saw many small shadows crowding near the grill in the wall next to the door, straining to look in. Their eyes gleamed in the half dark. She crawled back in superfast speed from the switchboard to the fortress, and crouched low again. Though the children chattered volubly, their small arms extending inside the room through the grill, pointing to this or that, she could not understand a word. It was a chattering buzz—loud, but coming from a great distance, the language familiar but unintelligible.

The late evening drew on interminably, and there was no other explanation for the time she spent in that classroom, but to believe that she had fallen asleep. She was woken again, this time rudely, with the loud clattering of footsteps and jingling keys. A huge torchlight beamed through the classroom grill, and male voices shouted her name, banging on every classroom door. She heard her parent’s voice calling, and she cried out in response, as her mother later remembered, sounding like a bleating lamb. They had discovered her! It took her some time to get uncrumpled from her half lying position, get up, switch on the light, stand on the dustbin and unbolt the door. She noticed, miserably, the small pool in the fortress next to her empty tiffin box. She had wet herself. Her parents spilt into the room, and her mother’s own face was unrecognizable with incessant crying. Though my friend had been rescued, there is no softer, sugar-coated, way of describing the dread many young children like her experience in situations of crisis.

In reality, it was not more than six hours after the last chartered busses had pulled away from school, that her parents, discovering that she had not come home, sprang into action. It had taken some time though since teachers had not reached their own homes as yet. The middle-school principle, the grounds keeper, the bus drivers of both the school-owned, and her chartered bus had been rounded up. A group of neighbours helping her father, had arrived on the spot. Yes, a person living in a tea-shop shanty outside the school walls, remembered to have seen a light in one of the classrooms. But he did not think much of it since students commonly forgot to switch off the lights during monsoon months. However, the strange part was that the lights were soon turned off, though a fuse blowing was not uncommon either. Yes, the school bus driver had seen her run inside, but had not seen her returning. The chartered bus driver, who had been slapped a couple of times was crying. He had not seen her, but he was not paid to keep an eye on the children. It was the schoolteacher’s job, and she was absent. My friend had unfortunately, slipped through the gaps.

She was, quite naturally, put on inquisition: her parents, a range of schoolteachers, administrators, principles, and social workers kept asking her repeatedly: what really happened? Why had she not come down? My friend could not adequately explain herself, and saying that the classroom looked serene sounded daft to her own ears by now. It was, moreover, the age of the first nuclear families, that expected their children to be perfectly intelligible, rational, half-adults, capable of explaining their acts according to a logical impeccability that superseded their maturity. They were supposed to help their parents build nuclear families by losing their own childhoods, that allowed for spontaneous, inexplicable, dreamy half-decisions that were not afraid of consequences. Moreover, it was Delhi. What if ‘something’ had happened, as if that ‘something’ did not already happen at home with distant uncle-jis. The school blamed the parents, and the parents blamed the school, and they both blamed my friend. My friend had developed an innate ability to tell ‘logical lies’ by then, to save herself from adult questioning, while somehow continuing to hold on to her freedom. But it was not easy, and now it had become impossible.

After this incident, her parents doubted whether she could be trusted enough to return to school. This doubt was especially exacerbated by when, as a result of giving way to the teacher’s battering, my friend told her about those children. The teacher looking at her in aghast askance, her disbelief slowly giving way to rage: how dare she lie so shamelessly?! If there were real ghosts, then a locked door or grill could not have kept them out! The teacher was an adult, and needless to say, honed in her knowledge of the supernatural through science fiction that paradoxically advocated for not being held to logic. The teacher pronounced the official version in a cold voice: she had fallen asleep, and that was it. Resolving to only rely on suitable narratives thereafter, my friend tried to harden herself. But it was difficult. The social worker advised her parents to seek psychological counselling for the child, who was way too imaginative and attention-seeking for her own good. Though it was not clear whether she was telling a lie to get out of trouble, or whether she had really fallen asleep and dreamed it all up, or both, the ‘truth’ no longer mattered, since it could not be ascertained. And besides, the child was physically safe.

The school principle was ambivalent about taking my friend back. It was not as if the incident would repeat, since she was certain my friend had learned her lesson. But it was a question of stigma. Other children would single her out, and torment her; it could harm her personality to return. And this was unsurprising; my friend’s own parents looked at her, as if they no longer recognized her. My friend missed two years of school thereafter, and returned to join two classes below her. She was a changed person when she returned. Very overweight by now, with two years spent at home, she was tentative, cautious, and deliberate. There was no question of re-joining the choir. There was a car and driver now, who dropped and picked her up from school. She was mostly silent, and constantly under surveillance. No one knew her two classes below, since that batch was in junior school when the event took place. Neither did she interact with earlier classmates, who soon went into their board exam year and had nothing else to worry about besides. She felt ashamed when she met any of them, and was surprised to later learn that none of them really knew what happened. It was obvious, there had been a crisis, since the school inexplicably tightened its security, but they thought it was an accident. It was true in a way.

Children inexplicably, lead internally different lives, that are invisible to most adults, who paradoxically, having lived through childhoods themselves, forget it with the onset of adulthood. It is as if childhood is necessary to be an adult, but it can be instantly forgotten upon reaching adulthood. The only memory that remains over, is a memory of vulnerability. I asked my friend what she thought of those ‘children ghosts’ for want of a better word. Were they the souls of past students? My friend, very deliberately, disagreed. She said she had spent many years thinking about what happened that night, and even spoken about it to a therapist to arrive at what could be an acceptable consensus. She said, places like schools had deep memories like pockets; memories of children’s lives spent over there, remained imprinted on its fourth dimension. The school was a united place and body—like a nation, or family. It was a clinical answer, and a chilling one. Stiffening at the realization of having told me too much, she shrugged. Perhaps, she said, in a small, hard, cold, and flat voice, she had indeed dreamed it all up!

My friend, in a small but significant way, had lost her childhood with that one lapse that ruptured her life. It was ironical. To preserve her freedom as a child, she had to become an adult. And once she had lost that childhood freedom, and filled with the trauma of exercising it any further, she could, in any case, kiss her childhood goodbye.

I thought repeatedly of my friend, as I read about the remains of children found at the residential school in Kamloops. What a shattering waste of childhood and innocence! What horrific pain the little ones underwent! And any way one wants to put it, accepting that a child hurt deeply enough to lose her childhood, and in case of Kamloops, her life, is one of the biggest travesties of our allegedly humane and just societies.

*

Add comment