Where is home, or what is it? How does one define home? For a word packed with a range of emotive and connotative layers, the word home evokes diverse responses among people. But what is it that constitutes a home? Is it the walls, the building, the people, or emotions? Situated within a complex matrix of sociocultural, psychological, emotional, economic, linguistic, political, and other factors, home for some is dwelling while for some others it is a space which they carry within, and for some, a final refuge they aspire for – hoping to attain it someday. To say, therefore, that home is where the heart is, would be too simplistic, depriving the word of its multi-layered identity.

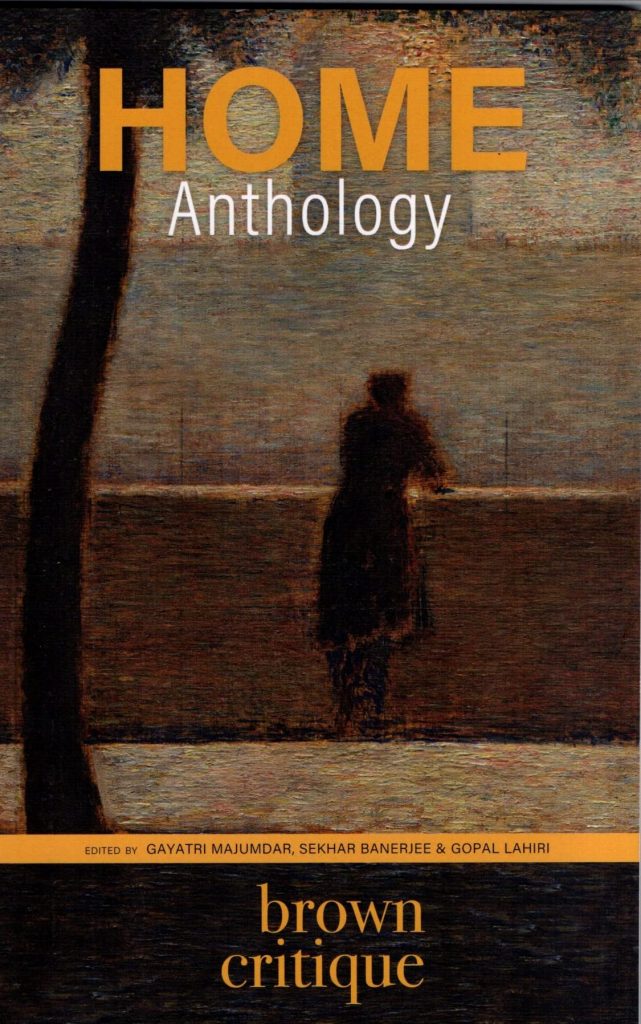

What happens when poets engage with this word in their verses? It results in a fascinating exploration of the word, celebrating its literal, metaphorical, and symbolic nuances. In this month’s Poetspeak, my focus is on the poetry collection, Home Anthology, jointly edited by Gayatri Majumdar, Sekhar Banerjee, and Gopal Lahiri, published by Brown Critique Books. This anthology is a sincere effort to engage with the idea of Home by looking at it through the poets’ understanding of the term.

Anthologies are important because they become the point of intersection of many voices. Each poem contributes to the collective and creates the text as a whole. In this anthology, the voices come together to create a home with multiple floors and many exit points with each poem parking itself in a unique space. Comprising fifty poets from all across the country, and a few from other parts of the world, this anthology, in the editors’ words, “excavates the modern narratives and is a meditation on the multidimensions of Home, and how the modernist poems with their identities and idiosyncracies might look about Home through the contemporary lens”. In the post-pandemic world, ‘Home’ has emerged as a contested site that is both a reality as well as an idea, depending upon the location of the individual. Homogeneity of the concept of ‘home’ as a safe refuge where we return, has been critically challenged by increasing domestic abuses or with the migrant workers failing to ‘return’ to their homes. This anthology engages with the concept of home in such a wide, critical context.

The anthology opens with the idea of the poem being the home of the poet. Abhay K. in his short, succinct lines, asks for his ashes to be scattered on the earth and,

“read my poems,

I live in them

they’re my home” (13, Abhay K.)

It is a short poem that deconstructs the idea of home as a concrete entity, locating it in the fluidity of words. For Sharmila Ray too, ‘home is a manuscript, you write and rewrite’ (96). In a few lines, the poem touches upon the range of both tangibles and intangibles that runs through a home, making it a dynamic but central space – ‘beaten out of love spent and unspent…’ or ‘a small galaxy in the universe of your life’ (97). The women at home and the concern with the act of drying clothes – an absolutely mundane activity but one that’s typical in Indian homes during the monsoons, finds a poetic makeover in Nikita Parikh’s poem, ‘Shapes of a Clothesline’ which engages with the domesticity of the space. The magic of the mundane finds an important place in this anthology, because what is home if not a collective of the mundane, the ordinary – Gopal Lahiri’s poem, ‘One Evening’, Geetha Nair’s ‘Cotton Pillow from Amazon’, Jagari Mukherjee’s ‘Abode’, all weave their poetry from simple, ordinary acts. Basudhara Roy, in her poem ‘This Dark House’ similarly seeks the magic that many refuse to see – ‘By now I have had enough of people who refuse to meet magic when they see it’ (26). By the simple act of opening the attic door, she lets in the magic, in her home, where ‘rooms were built to hold grief’ (26).

Yet home is also memories, painted in nostalgic shades. Anju Makhija’s ‘Abandoning the Farmhouse’ is a long narrative that is filled with nostalgia. What happens when one has to leave home yet cannot move away from its memories? The poem has an anxious tone which culminates in a hope of togetherness – ‘I grip the table, I am alive/ and you are beside me’ (23) and that is all it takes to make a home. Purabi Bhattacharya’s ‘Dear Home’, Sonnet Mondal’s ‘No One to Wait at the Doorstep’, Sonya Nair’s ‘The Houses of Nattalam’, all speak of homes that were, that now stay on in memories. If memory is an exploration of the past, death is an end. Gayatri Majumdar, explores the idea of home in death. If death is the end of all experiences, it is only apt to be the final repose, where all wished for and pending desires flock together.

Home includes within itself the idea of homelessness. In a world of uncertainties, Aneek Chatterjee, on the other side of this spectrum, talks about the absence of home, ‘the ephemeral home’ – a makeshift shelter where ‘unwanted tree pretends to keep guard’ (18). Jane Bhandari, in ‘The Exiles’, brings in two ways of losing home – while for the father-in-law, it was an exile from his ‘land of birth’, for her mother-in-law, it was ‘lost’ ‘by marriage’ (58). In ‘Foreign Shores/ Remembered Homes’, Sunil Sharma juxtaposes the home that one finds in foreign shores with the home one leaves behind – ‘the poignant moment/ connects a phantom/ with another phantom’ (102). Amanita Sen’s ‘Homeless’ is an exploration of loss, from the ‘red water bottle lost in the school bus’ to ‘the coldness of obliteration’. Is the loss of home, also the loss of a beloved? Can we resurrect the lost home in our dreams? Some questions have no answers, just as all homes are not happy ones. ‘Where the Heart is, Is not Always a Home’, by Candice Louisa Daquin, ‘where the heart is, is not always home/ it lays still, a wasteland of unsaid things’ (32).

The poems in this anthology go beyond the idea of a physical home to include the macrocosm of one’s immediate ecology, and even the larger concept of the entire earth. Sekhar Banerjee’s poems, ‘Monsoon in a Tea Garden’ and ‘In a Gooseberry Forest’ evoke the idea of the place along with its local flavours. Home does not remain confined within four walls but consists of all that is familiar, all that is in the surrounding. Usha Akella, ‘In Memory of Rydal Mount’ says, ‘home is a minutia of signs – rock, cataract, grass, lakes, mountain, vale and humanity – one you heard the music of one in another’ (109). In the tradition of eco-poetry the poet finds home in the harmony of nature, in human existence as a part of its ecology.

For Vinita Agarwal, the existence of a home for herself also evokes guilt – ‘I am guilty of a roof over my head, of the rent not burning a hole in my pocket’ (110). The home becomes a crusade, a place of togetherness. The home – a place of love and dependence, or a migrant’s dream.

This anthology brings together myriad strings of ‘home’ as a concept. It ruptures the uniformity of idea that has been traditionally associated with it. The poems are well chosen, to represent the multiplicity of ideas and the editors have done an excellent job in bringing together so many amazing poetic voices – both old and new, within the same cover. This is an important anthology that builds and breaks and re-frames the idea of home and allows readers to imaginatively, creatively, emotionally, and cerebrally explore the idea of a very mundane and everyday word that carries so much within itself!

*

Add comment