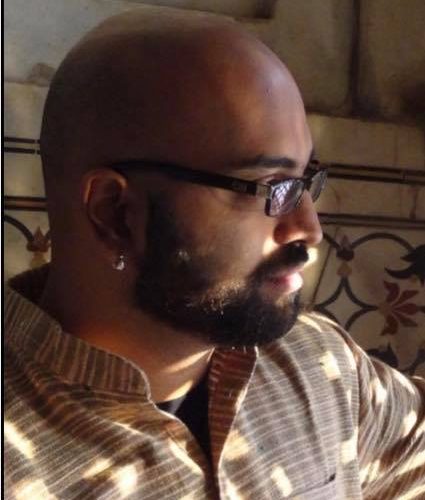

Rajiv Mohabir is an inspiring name right now in contemporary American poetry. Mohabir’s memoir Antiman will be out this month. A conversation with Mohabir–

When was that magic moment that turned you into a poet?

I don’t know if there was one single moment. Poetry came to me like a slow burn than a sudden realization. I write about my journey into poetry in my forthcoming memoir Antiman (https://restlessbooks.org/bookstore/antiman). Basically, I came to poetry through my Aji’s songs in Bhojpuri. Afsarji, I met you right at that moment in Madison, Wisconsin. I remember singing one of my Aji’s songs in the annual performances and I remember translating the words of the song for my sister who came to visit.

I think that language learning, poetry, and folk songs have all been instrumental in forming my ideas of what poetry can be. As an undergraduate I was a religious studies major and was deeply moved by the poems of the Christian bible, by Kabir, Tulsidas, Mira, Ravidas, as well as the alvars Andal and Namalvar.

During your formative years as a poet/reader, who were your ideals?

Along with the poets I mention above I also looked to as I was beginning to understand my life through poems were Audre Lorde, Joy Harjo, Agha Shahid Ali, Derek Walcott, Kimiko Hahn, Rigoberto González, Nicole Cooley, Craig Santos Perez, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Arun Kolatkar, Kamau Brathwaite, and David Dabydeen.

I’m still an active follower of the careers of these poets that are still writing and translating. I am also a fan of poets like Hari Alluri, Faisal Mohyuddin, Adeeba Shahid Talukder, George Abraham, Kazim Ali, Cathy Linh Che, Tamiko Beyer, John Murillo, and so many others.

I like poems that have clear stakes and that work to shift paradigms. I think that culturally poetry exists in a different place in society in the United States—it’s rarified and pedestalized which works counter to the ways that in brown countries poetry challenges authority and springs from the throats of regular, everyday people.

How important is the location of your family in your poetry?

My family is there—I write about them some, but I also write for them at times too. I think the thing that marks my poems is that I am writing with brown speakers. Questions naturally follow from the white world about how people can understand my own particular Caribbean South Asian family dynamics. Family will always be a fraught consideration for me: estrangements, engagements, and queernesses all temper my approach to writing people in my life.

If someone asks you about the essence of Rajiv Mohabir, is there anyway that you can put it into words?

I don’t know. I think this is a question better posed to someone not so close to my work as I am. I would say there are some traits that my writing has though. I am obsessed with multilingual writing. I love mythologies of the places I come from. I can see my work as American, Caribbean, South Asian, and indelibly marked by migration and translation.

Finally, what makes a good poem really good?

I’m not sure that I think of poems in terms of “good” and “bad” but rather I notice what happens to me as I read them. Am I moved? Are the stakes particularly resonant to me? Is the language texture appealing or does it accomplish something in the poem? Is there a magic spell that bewitches me?

I also like to ask about what the images do in the poem. Are there layers and complications? Is the poem straightforward? Convoluted doesn’t always mean moving.

*

Thanks for introducing a poet with a difference. An interview worth sharing and saving!