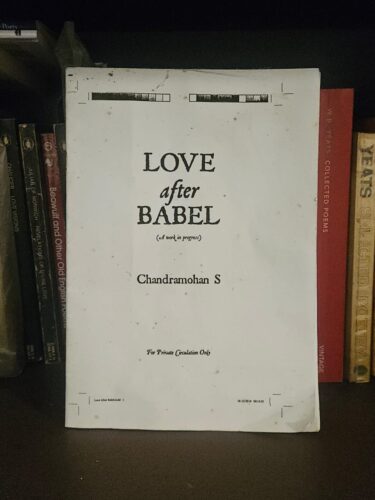

Chandramohan S.’s Love after Babel is a collection of poems that deals with nuances of translation, caste, language and identity, reimagining the lineage and legacy of creative writing in English from Kerala. Kerala writing in English, as a phenomenon in general, has a long and complex history, shaped by the introduction of English education under colonial rule and carried forward through generations of writers who negotiated between regional grounding and transnational reach.

Writers such as Menon Marath, Aubrey Menon, K. P. S. Menon, Manjeri Isvaran, A. S. P. Ayyar and Kamala Das, gave the field its early contours, and their works ranged from memoir and travelogue to poetry and fiction. The recent decades—particularly after the disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic—have witnessed a renewed flourishing of creative writing in English, with many writers experimenting myriad forms and possibilities. Within this diverse tradition, Chandramohan S. stands out as one of the few Dalit poets from Kerala to write in English, while much of the writing from the margins has historically leaned towards non-fictional forms. His poetry foregrounds the intersections of caste, language, translation and globalisation, offering a radically different perspective from the largely privileged voices that have dominated Kerala’s literary presence in English. In doing so, he both inherits and disrupts Kerala’s literary lineage, situating Dalit experience and vernacular anxieties at the centre of contemporary poetics.

Chandramohan approaches poetry not merely as a craft of aesthetic expression, but as a political and cultural tool of resistance. The title echoes George Steiner’s After Babel, positioning the text within the contested history of translation and linguistic hegemony. Yet, the poems here do not rehearse abstract debates of translation theory in mere academic terms; they embody, dramatise and often parody the violence of language, the complexities of translation, and the fractures left behind by colonial and caste histories. Love after Babel is fragmented and episodic, composed of short poems, aphoristic declarations and extended metaphors. Each poem stages a conflict between language and power, between translation and betrayal, between vernacular rootedness and cosmopolitan circulation.

Translation and the Politics of Untranslatability

From the opening poem, “The Muse in the Market Place,” Chandramohan foregrounds the violence that poems undergo in the process of translation and global reception. The idea of translation appears here in a subtle, metaphorical sense rather than in a direct way—as an event that happens from within. The need and dilemma of a writer presenting himself in the global market runs through his poems, revealing how certain cultures are banished or forcefully adapted to meet the demands of literary festivals and globalisation. In this sense, the book emerges as a critique of globalisation itself, as he talks about how languages and histories adapt into the needs of the dominant. I recall one of the early travelogues in Malayalam by Malayattoor Ramakrishnan, where he describes having to wait on the road for approval to cross from one country to another. Similarly, Chandramohan metaphorically depicts how Dalit literature in general feels when transported from one culture to another—how the poem must adapt itself as a catering item, tailored to fit the dining halls of the global market and its audiences.

Throughout the collection, translation is imagined as distortion: “A poem and its translation are / like a pair of lopsided breasts.” The irreverence here, almost grotesque, unsettles the reverence with which bilingual editions or so-called ‘faithful’ translations are usually received. The idea that “a translated poem is always in transit” lingers within me, where he presents translation not as fidelity but as a perpetual wandering, like a flock of birds in flight, scripting camaraderie but never quite arriving. What emerges is an insistence that untranslatability is not a failure but a form of resistance, a refusal to be absorbed into homogenising empires of language.

Dalit Vernacular and the Politics of Resistance

English came to Kerala through the schools the British set up, and even after Independence in 1947, it stayed on as part of the state’s curriculum and public life. For Malayalis, it became a language met early in childhood, carried into memory, speech and imagination, until it feels almost like blood running through the veins. From here begins the dilemma Chandramohan points to when he speaks of language. It is not about Malayalam alone, nor about English in its pure form, but about the space in between—a Malayalamised English, or an Englishicised Malayalam. Bilingual writing grows out of this space, pulled towards a global audience yet held back by the pull of the vernacular. It is like the life of an amphibian, moving across two worlds, belonging both nowhere and everywhere, shifting between tongues that give as much as they take away. Out of this condition of language, Love after Babel finds its strength.

The collection gains its most powerful edge in poems that directly address the position of the Dalit vernacular, and “My Language” is one of the most explicit in this regard. Alien tongues introduced in schools are compared to dams built too close to river origins, sedating rivers for eternity. The metaphor of dams is at once ecological and political, foregrounding how imposition of dominant languages disrupts the organic flow of vernacular life. Yet a dam also creates material spaces, in reservoirs, electricity, even tourism, reminding us that what is gained is inseparable from what is drowned. Further, the reference to “suicide notes” and “slave owners’ legacy” inscribed in the hardbound of poetry books invokes the historical silencing of Dalit voices. Language is figured as a site of mourning, but also as a weapon of resistance: “I am a martyr of my language!” In this sense, Chandramohan refuses to treat the Dalit vernacular as a relic of folklore; instead, he renders it as a wounded, bleeding body that refuses assimilation. Language, for Chandramohan, carries a ruinous legacy: “The autobiography of my vernacular / there were a few suicide notes / transliterated with indelible ink.” The market, too, appears as a stage of estrangement. In streets where a beggar speaks in the vernacular, the poet overhears echoes of exile. Like empire, the market speaks a homogenising tongue, erasing dialects and scattering kin into drifting islands. Against this, Chandramohan positions his own vernacular as a site of fidelity, pain and survival. These poems stand as a critique of empire, of globalisation, and of every form of linguistic homogeny.

Intertextuality and Lineage

The references to Walt Whitman, Roberto Bolaño, Derek Walcott and George Steiner place Chandramohan within a global literary lineage, yet these references are never imitative; they are appropriated and localised. When he cites Walcott’s “grammar is a form of history,” he is not merely echoing but re-scripting it in Dalit terms. Similarly, the echoes of Namdeo Dhasal, to whom Chandramohan has dedicated another volume, are present in the irreverence, the bodily metaphors, and the refusal of sanitised lyricism. The intertexts thus situate Love after Babel in dialogue with global poetics of postcolonial resistance, while firmly anchoring it in Dalit realities. Yet one notices the relative absence of Malayalam writers in this constellation, a silence that gestures towards the dilemma of a poet moving from a bilingual space into the narrower corridors of a monolingual one.

Chandramohan’s poems juxtapose questions of vernacular identity, caste and globalisation, exposing how language itself becomes a contested site—at once wounded and resistant, scarred yet alive. His refusal to treat the Dalit vernacular as either folklore or ornament situates it instead as a living body, marked by pain but also by survival. In foregrounding the homogenising pressures of empire and the market, he demonstrates how English, even when appropriated, cannot erase the memory of silenced voices. What emerges is a poetics that unsettles both global and local expectations: bilingual yet uneasy, vernacular yet cosmopolitan. These poems, in their irreverence and defiance, extend Kerala’s literary tradition into new terrain, insisting that the vernacular must speak, however fractured, within and against the global order.

*

Add comment