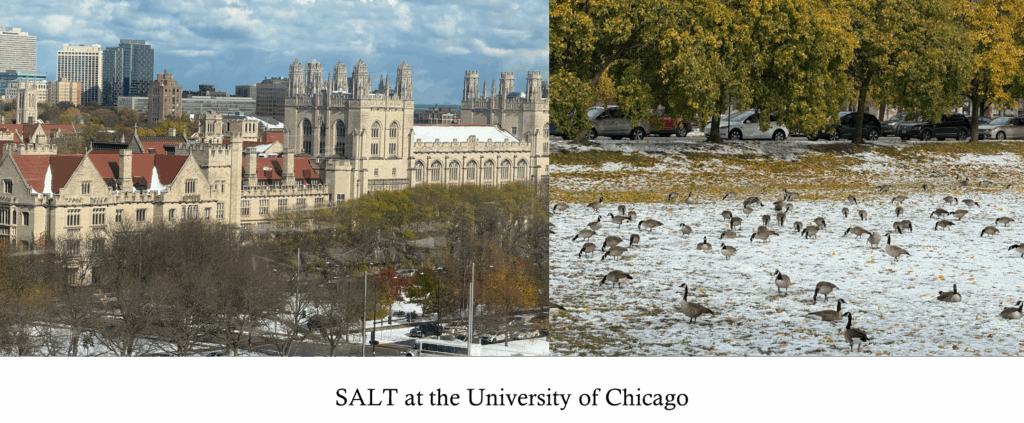

It was a snowy afternoon on the second Sunday of November this year. Roughly eighteen of us had gathered in a gothic building called Forster Hall at the University of Chicago, after four days together in sunny Tucson, Arizona. Half of us were emerging translators, working on our first book-length projects, while the other half were our literary translation mentors, who had decades of experience in South Asian languages behind them.

Together, we were all seated in a classroom on the ground floor where large windows looked out at the snowclad Midway Plaisance Park. In the very same classroom, AK Ramanujan had taught his last literary translation workshop at the University of Chicago, weeks before he passed away. Back in the 1990s, that fated translation workshop had led my mentor, Daisy Rockwell, to literary translation. My fellow mentee, Sadia Khatri, and I were gushing in disbelief that we were breathing the same air. Some of AK Ramanujan’s ideas about translation had made it into my own mentorship, and so it struck me just how much has been disseminated to me over the past year.

As we all ate sandwiches and the iconic “garbage cookies” from the Medici, Professor Jason Grunebaum who heads the South Asian Literature in Translation project talked to us about the mentorship year and about what comes next. At that moment, it was humbling to learn that this was only the second year of the SALT project and that these efforts had been in the making for almost a decade. Just three years ago, there wasn’t so much as a dedicated category for literary translation mentorships from South Asian languages at the American Literary Translators Association, making my fellow mentees and me some of the earliest beneficiaries of dedicated support in our languages. This cohort itself evidenced a wide range of projects, including centuries-old poetry collections, novels, and short story collections from different parts of the country.

This time, even at the ALTA conference in Tucson, we had seen a whole day’s worth of panel discussions and readings dedicated to South Asian literary translations. The conference itself was a 4-day event, full of panels from morning till evening followed by off-site readings of poetry in translation and even a performance of a translated play! It took place downtown at the Marriott hotel, near the University of Arizona campus, where some mentees were even able to see original copies of translations by Agha Shahid Ali.

Besides the emerging translator readings from ALTA mentees like myself, and readings from some of the SALT mentors, the South Asian programming at ALTA also included a panel on editing South Asian translations and another on the Bangla literary scene. Even mentees from the previous year resurfaced at such events, like Subhashree Beeman who published her work through the First Look program we’ll soon be participating in, and who has now completed a number of projects from various languages.

Seeing some of the previous mentees shine was deeply inspiring, partly because of the uncertainty around establishing oneself after the program. The week before coming to Tucson for the conference, I’d met Anton Hur at his translation workshop in London where he talked to us about the very same anxieties, as expressed in his essay on “The Emerging Literary Translator Valley of Death.” As Professor Grunebaum and others spoke about what happens after our mentorships, I realized that a new flock of emerging translators would already be scrambling to send samples and project proposals for their mentorship applications to ALTA, just as we had done the previous year.

That said, several activities remained even after this lunch at Forster Hall. A few of these included a day of panels at the Logan Center, where we learned about how humanities faculty across departments at the University of Chicago are using literary translation in their coursework for pedagogical outcomes. Other fun components of the SALT programming included a translation workshop with a few University of Chicago students, including medievalists working in older variants of South Asian languages. Besides these, we also had a few spontaneous runs around campus to its many museums and its library, which all featured surprising instances of translation.

Our last event in Chicago was a big mentor and mentee reading at the South Asia Institute downtown. The Institute, which has a stunning art gallery featuring varied pieces by painters from India and Pakistan around its seating area, offered a different context for our readings of our literary translations. At the ALTA conference, most of the attendees I met at our readings were fellow translators who were working in various languages, who were largely experienced with publishing or were affiliated with academia. On the other hand, at the reading in Chicago, we met with interested people from across the city, many of whom were neither academics nor necessarily pursuing their own translations. Given the precarious landscape around funding for literary translation and for publishing, it was especially heartening to see how the work we all have been doing held genuine value for people in the city and piqued their curiosity even if they did not have South Asian roots.

The final step of our journey together is going to be yet another entirely different context for our translation practice. The mentees will be going — without our mentors, for the first time — to the London Book Fair in March, where we will most likely be at a booth for South Asian Literature in Translation.

*

This is what is missing in Indian translation arena. The workshops in India cannot be comprehensive and all inclusive due to the multicultural and multilingual nature Indian society.There cannot be one mantra for all languages and literatures. One nodal organization is the need of the hour