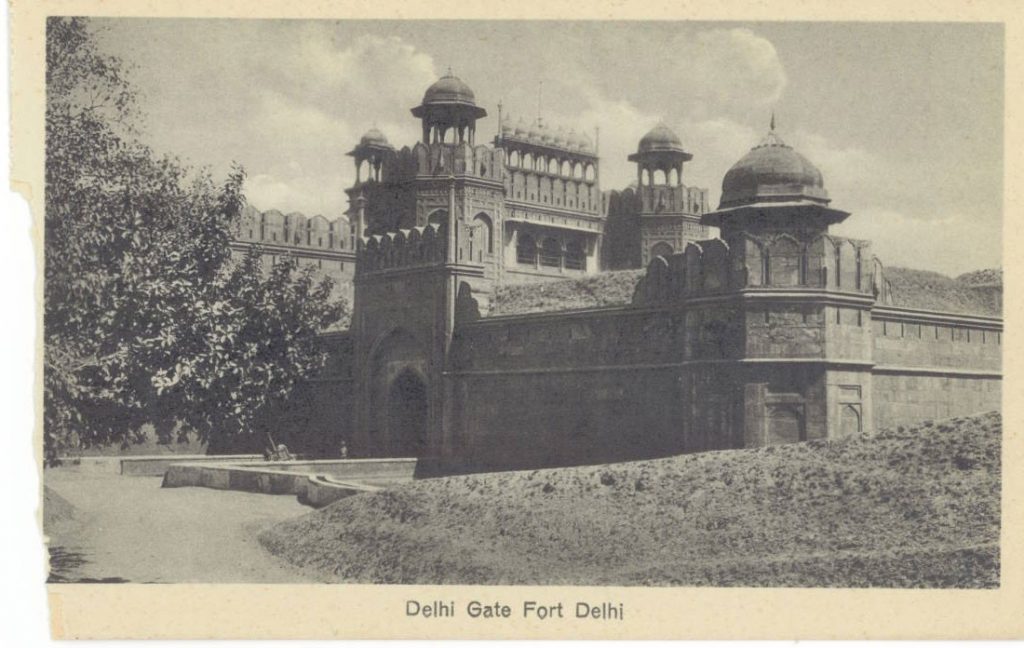

The Red Fort is central for Dilli-wallahs, especially for those of us who are descended from families that have already spent a few generations in the city. For us, Delhi is hardly the malls of South Extension, or the posh residential enclaves and markets of Vasant Vihar, Khan Market, or Gurugram. For us, Delhi is the Red Fort. Of course, there is an extended area surrounding it that includes the region immediately north of Kashmiri Gate – Delhi University’s north campus. On the other side, Delhi extends, at least in the minds of old-time Dilli-wallahs, to the area immediately south of Ajmeri Gate, and the Khooni Darwaza to Connaught Place – Nai Dilli. Delhi’s western parts that became settled more or less after the Partition is not really part of that emotional heartland. Purana Quila, Firoz Shah Kotla, the Qutub complex, and other ‘cities’ are hardly part of that Old Delhi heartland either that is Shahjahanabad-extended, with its iconic centre at the Red Fort.

Cities are hardly spatial and administrative hubs – though that too; they are also places in the mind that are nostalgic and associated with relationships. This ‘memory-feeling’ of Delhi is best explained by Ravish Kumar’s poignant collection of Hindi short stories about Delhi, called Ishq mein Shahar Hona. Ravish Kumar describes Delhi as an experience known through the places inhabited by lovers – anonymous places of quiet, private romance, cleaved and produced within small personal bubbles of intimate memory and emotion that are located within larger, impersonal spaces.

For me, Delhi is my childhood and youth. It was spent exactly in carving out those intimate niches located in the city’s unfriendliness to women. This rendered the pleasure of those bubble spaces more poignant, especially as they subverted the violent city – a survival mode that often turns into an addiction, a way of negotiating a world that is never lost once learned – once a Dilli-wallah always a Dilli-wallah! This can hardly be explained to non-Dilli-wallahs who see it as a response to violence and squalor. It is hard for us to separate Delhi from bubbles of memory-emotions that contain intense friendships, and budding romances, that are part of Delhi itself. In other more ‘equal’ cities, though freedom and independence is higher, its equality is not necessarily reflected within intimate bubble spaces, that instead sometimes, and unfortunately, compensate for this equality of the outside. Delhi is deeply violent and ruthless, but it is also deeply tolerant and loving, and this is not a paradox. It is inter-related.

Delhi was also my father’s city. After immersing his ashes in the Yamuna at the city’s huge crematorium – the Nigambodh Ghat, the city of Delhi has slowly merged in my mind, with my father, the dark ribbon of the river every time my plane hovers over Delhi, constituting my reunion with him, and with the city. Before my father, Delhi had been my grandfather’s city, who had arrived here in the wake of the capital shift from Calcutta, and who had become a central figure for the many other praboshi bangali families of his time who had also arrived in Delhi. For my father, the Red Fort was always the centre of life, and I inherited that love.

Born in Sitaram Bazaar, the family later shifted to Kashmiri Gate into an apartment that had its back windows facing the Old Delhi Railway Station. It was from these windows that my father first saw trains full of corpses arriving from Pakistan in 1947. Though his parents had told him not to look, he always said, one could ‘smell’ those trains. The monsoon heat made it worse. One could also ‘feel’ their arrival in the dark, angry, and silent masses of men, who stood in dense crowds at the railway station.

It was at the Red Fort that my father saw Mountbatten standing aside, as Jawaharlal Nehru unfurled the national flag. Unfortunately, he lost one of his slippers in the crowds that day as the grounds had become muddy. Later when he studied for exams, my father said he often went to the lawns of the Red Fort. He would either walk across the Old Delhi Railway Station overbridge, or he would take a bus from the GPO. The habit stayed with us. My parents and I often went to the Red Fort on Sundays, lazed around, ate at gali parathewali, and then walked over to the old house in Kashmiri Gate – a place completely colonized by the automobile market. My father did not remember his old house at Sitaram Bazaar, and only knew the Kashmiri Gate one. We would stand there, looking up at the house, at the boarded-up windows and try to ‘see’ that place from where my father had seen, smelled, heard, and felt the trains arriving. It was like visiting a separate historical layer of the city, lived by people from an earlier generation.

My father had interesting observations about the Red Fort, where he said he spied snakes as thick as his thigh. Also, from the ramparts one could see the small doors on the outside lower walls, still in use by washermen and vegetable vendors for the army personnel living inside. Now these doors have largely been hidden from sight by the height of the Ring Road. Earlier, the Ring Road was an ordinary road separating the Yamuna from the Red Fort and Saleemgarh, used for jailing political prisoners. All the memorials for important politicians beginning from Mahatma Gandhi’s at Raj Ghat were on the banks of the Yamuna, down the stretch from Nigambodh Ghat. This road that went on to the Purana Quila was said to be haunted, as it flanked the Yamuna and was used for cremation. The Ring Road was certainly spooky at night, illuminated by yellow neon lights, the cold, sandy winds blowing in from the Yamuna against the darkened Red Fort, howling in the night.

I must have been about ten, on my way down the Ring Road towards North Delhi, when I thought I saw flickering lights, sounds of explosive laughter, singing, and marching emanating from inside the Red Fort. As the back portion of the Fort stood out in gloomy darkness, it quivered in that spooky light. It was many years later, after moving away from Delhi that I recognized the flickering, quivering lights and sounds that I had seen from the Ring Road as a child. It was the Red Fort’s sound-and-light program!

Though I had seen the program many times, I had never ‘recognized’ what I had seen as an impressionable child from the other side of the Red Fort from the Ring Road, peering up at the darkened shape that was alight. Could the distance from that side of the Ring Road to now, sitting on its other side, be measured? Could the distance of a young man’s youth spent studying at the Red Fort be measured in terms of linear time? Or were these ages – disjointed layers, lived in separate bubbles? Was the distance between Lahore and Delhi so great that it changed human beings, or did these cities exist in separate bubbles that co-constituted and coped with violent times? Did Mountbatten and Nehru live in separate time warps constituted by different interests? What had remained eternal and tolerant of it all throughout, like a palimpsest made up of spaces, memories, and relationships?

*

Wow… I started admiring Dilli with Maniratnam movies in childhood. Ur narration took me to those memories. So impressive

Beautifully portrayed the romance of Delhi