In ‘Bateshwar’s Contribution’, a short film by Sandip Ray I recently watched, Bateshwar Sikdar, a veteran writer, suddenly finds himself in the company of visitors and advice – both unsolicited. Over the course of three days, as many individuals, supposedly Sikdar’s fans come to him with the same strange request. They all want him to make the ending of a novel he’s writing, a happy one. Based on a story by Rajshekhar Basu, often hailed as the greatest humourist of the last century, the film, or rather that peculiar request, struck a personal chord with me in what has been my nascent journey into published authorship so far. I am coming to that in a bit.

In Sikdar’s case, when the first reader, a young man, approaches him on one of his morning walks, there isn’t much to suspect – he’s seen gushing with praise for the senior writer and shows great interest in his current serialized work ‘Ke Thaakey, Ke Jaaye?’ (Who Stays, Who Goes?). In fact, he seems so involved with the story that he’s eager to find out the fate of a female character. He asks Sikdar about the same, referring to the character as the novel’s heroine. Sikdar reminds him that there are two heroines in the novel, and when the young reader specifies he’s referring to Aloka who is fighting a serious illness, Sikdar tells him that she’s going to die. Our young reader seems heartbroken and pleads with the author to let her live. Exasperated, Sikdar tells him off and continues on his walk. The next morning, the entreaty turns into a mild threat when another man, a renowned surgeon, drops by at Bateshwar’s house with the same proposition – to let Aloka live. As with the first petitioner, Sikdar turns down the physician’s request and remains firm on his stand to eliminate Aloka to have Sharbari, the novel’s other heroine, take her place. He would have a third and final requester – a woman who introduces herself as a film actor – who comes to him with the offer of buying the film rights for ‘Who Stays, Who Goes?’. She’s eager to play Aloka in the film she informs Sikdar, but he has to ensure she’s cured of her illness and continues to live. Sikdar, though excited at the offer, still remains reluctant to change his story’s ending. It’s only when the lady threatens to jump ship and make a similar offer to a rival author that he reverses his long-held decision to let Aloka die.

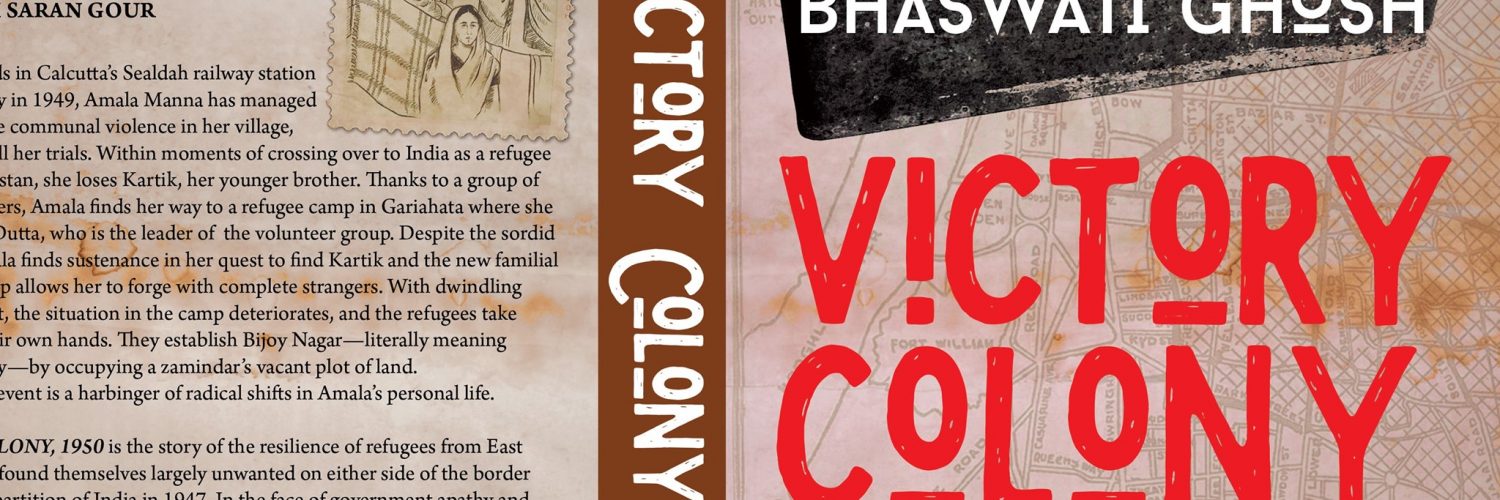

As amusing as the story was, it stirred me personally because of certain reader reactions to my recently published debut novel, ‘Victory Colony, 1950’. The book centres on Amala Manna, a young woman, who, after losing her parents and all her belongings in East Pakistan, crosses over to India in 1949 with her brother to escape Partition violence. Soon after landing in India, she is separated from Kartik, her little brother and only remaining family. The novel’s narrative arc follows Amala’s journey in Calcutta; her search for her brother forms a key part of that. When I first conceived the story, I had envisaged for Amala a happy resolution. After all the travails she has to endure, finding her brother would be the very least that could restore some balance to her forever-altered reality. So that’s how I wrote it. But I wasn’t sure if it would resonate with readers, if it were convincing enough. When I shared it with two of my trusted beta readers, one of them my husband, they confirmed my worst fears. The “happy ending” was a cop-out they suggested as it meant my avoidance of difficult truths. Since I valued both my readers’ opinions dearly, I rewrote the ending. It’s funny, how in my case, the suggestion was the opposite of what it was for Sikdar – to make the ending more realistic, even if it were sad. Strangely enough, the alternative ending didn’t cut it with some other beta readers, leaving me in a dilemma. I won’t reveal here which denouement I finally decided to go with, but as I watched the film, I could feel Sikdar’s perplexity quite viscerally.

As amusing as the story was, it stirred me personally because of certain reader reactions to my recently published debut novel, ‘Victory Colony, 1950’. The book centres on Amala Manna, a young woman, who, after losing her parents and all her belongings in East Pakistan, crosses over to India in 1949 with her brother to escape Partition violence. Soon after landing in India, she is separated from Kartik, her little brother and only remaining family. The novel’s narrative arc follows Amala’s journey in Calcutta; her search for her brother forms a key part of that. When I first conceived the story, I had envisaged for Amala a happy resolution. After all the travails she has to endure, finding her brother would be the very least that could restore some balance to her forever-altered reality. So that’s how I wrote it. But I wasn’t sure if it would resonate with readers, if it were convincing enough. When I shared it with two of my trusted beta readers, one of them my husband, they confirmed my worst fears. The “happy ending” was a cop-out they suggested as it meant my avoidance of difficult truths. Since I valued both my readers’ opinions dearly, I rewrote the ending. It’s funny, how in my case, the suggestion was the opposite of what it was for Sikdar – to make the ending more realistic, even if it were sad. Strangely enough, the alternative ending didn’t cut it with some other beta readers, leaving me in a dilemma. I won’t reveal here which denouement I finally decided to go with, but as I watched the film, I could feel Sikdar’s perplexity quite viscerally.

Writing a novel told me how hard endings can be. As the person closest to the story, the novelist is in a catch-22 situation. While she has the benefit of being close to the entire journey of the key characters, this extreme proximity comes with unconscious biases and the illusion of control. It can be a gamble in the end, depending on what readers – arguably the final arbiters in this case — feel about the book’s conclusion. As I looked for anecdotes on this topic, I came to know how Charles Dickens had had to change the ending of ‘Great Expectations’ after his friend Edward Bulwer-Lytton complained about how cheerlessly Dickens’ original draft ended, with Pip leaving with the knowledge that he and Estella won’t be together again.

In Rajshekhar Basu’s story, we learn about the connection between and the real motive of the three petitioning readers only in the end. It’s to do with the young man’s wife, who, while convalescing from a serious illness at a hospital, reads the instalments of ‘Who Stays, Who Goes?’ and becomes obsessed with the fate of Aloka, her namesake in the novel. She becomes convinced that her own recovery is linked to that of the fictional character.

In December 2020, about three months into my book’s publication, I received an email from a friend, himself a well-regarded author. The note had twofold joy for me – I was hearing from my friend after a long time as he had disappeared from social media networks for more than a year, and he had emailed me to say how much he was enjoying ‘Victory Colony, 1950’. While I was naturally elated to read that, the last part of his message made me chuckle. “I just hope that Amala is able to find Kartik in the end. I just hope that ‘Victory Colony 1950’ does not end like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’ in which Olanna is not able to find Kainene,” he wrote. This was my Sikdar moment, when I realized how a reader’s experiences, whether driven by one’s personal circumstances or a past reading, can shape their expectations of how a book’s plot should evolve. I remembered how other friends who were reading my book had shared their anxiousness over the outcome of Manas’s (the book’s male protagonist) proposal to Amala. Like Sikdar, this knowledge – that readers were connecting enough with characters I had imagined to invest in their ‘futures’– made my heart grow warm.

For an author, whether it’s her first book or twenty first, fewer things can be more rewarding than a reader (yes, even a single one) bonding with their characters and talking about them as if they were real people.

*

What an insightful article! I’m reviewing the ending of a new novel and of course the ending has ‘come up again.’ Thank you for writing this!