1: Who Needs Saving?

Every day in quarantine, we wake up to news of suffering. For those of us away from home, or trying to forge new homes, the scale of this suffering becomes overwhelming. How much can we care about? Where do we channel our concerns? I think of the classic dialogue from Telugu movies, where the news is always comically frustrating: anni chaavu kaburlena? But sometimes, the question takes on a quieter tone—is it all suffering? When will it end? What can we do about it?

Perhaps mercifully, one thing that we are being encouraged to do is nothing. Doing nothing is a protective gesture. Stay at home. Sometimes, helping can be useless or even detrimental. We must be wary of rushing to save others. Aren’t we so familiar with the elite, self-styled activist who tries to “rescue” people without really engaging with their conditions? To “save” without understanding from what people need to be saved from? As Nandini Dhar reminds us, words like dissent and resistance have become sexy. And underneath the desire to be sexy, there might be a guilt, maybe a voice in our heads: how dare you do anything for yourself if so much suffering exists in the world?

In Gamyam (2008), Abhiram magnanimously throws his Armani jacket on a homeless man in a park, only for him to wipe the bench with it. Janaki, the socially-minded woman he is trying to impress, laughs at him: “Could have bought 80 blankets with that.”

Abhiram and Janaki’s story tells us a lot about savior mindsets. The film, unlike many others that we are used to (see: Leader, 2010), never presents suffering people as victims to be saved. Janaki’s problem with Abhiram’s elitist mindset is not that of a revolutionary against the billionaire class. Rather, she stresses that it is he that is impoverished by his money—he is so preoccupied with his own comforts, she says, that he cannot even accept love if he receives it. This is the main idea of the film’s presentation of suffering: while we do see poverty, hunger, and disease (the usual conditions for a hero to step in and save the day), the main victim here is the rich man, whose ability to access humanity has been short-circuited. It is Abhiram that need to be rescued.

Then again, the rescuing arc of such characters has a cost. The flipside of it all is that the landscape of suffering has now transformed into a space where Abhiram can now “find himself”, like so many photographers who willfully live in poverty to “see how the other half lives.” With a reformed bike thief named Gaali Seenu, he travels across Andhra looking for Janaki, only to find that the journey has taught him empathy and kind-heartedness. We must be very careful when thinking about this space of transformation, making sure that we neither romanticize it nor turn it into a space of perpetual suffering.

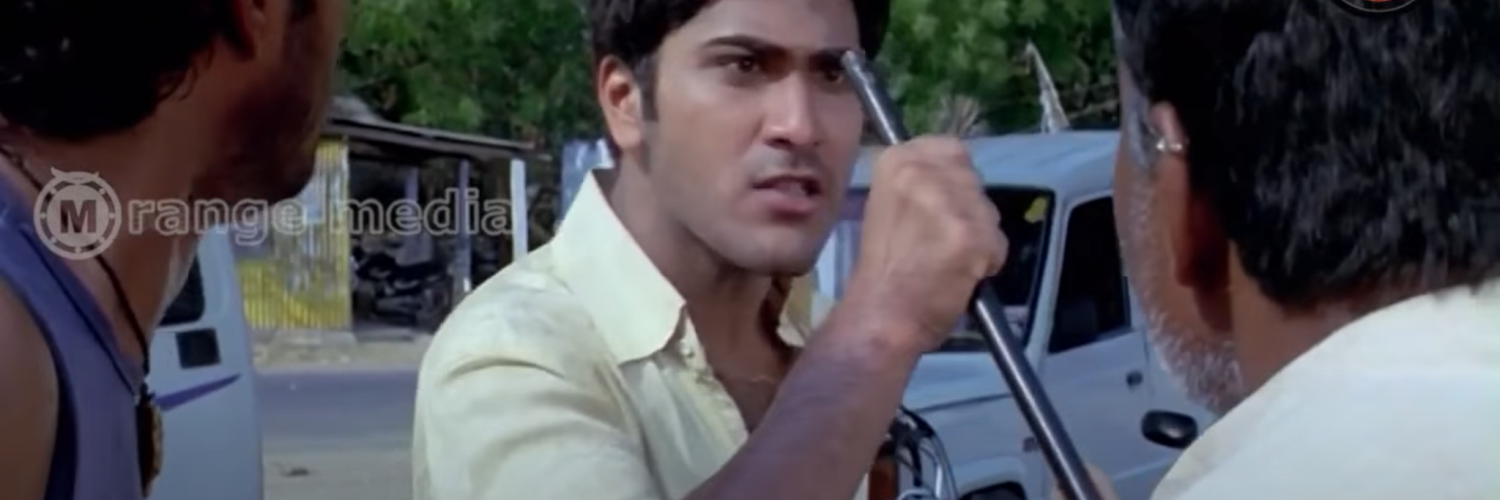

Abhiram’s character is strongest when he is giving up the very things that we are trained to obsessively protect. These points in the film make for poignant cinematic moments. Just before Abhiram leaves, he tosses his phone into his friend’s hands. When he finds out that Seenu wants to steal his bike, he gives him more money than the bike would sell for. When Abhiram and Seenu are harassed by members of a Rayalaseema gang, he doesn’t simply knock them out with super-human ability like a normal Telugu hero. He holds the enemy’s gun against his own head, daring the gangster to shoot. The rich man regains his humanity by giving up the things that make him safe.

2: Making the World Visible

There is a safety in being cut off from everything. Even better if you can be cut off and act like you aren’t. The internet has made this so much easier for us. Being cut off makes certain things invisible to us, even if they are generally accepted truths. In 2020, these ideas take on a striking intensity. All of a sudden, the question becomes: can you afford to cut yourself off? Do you have a space to cut yourself off? Are you privileged enough to be safe and hide from the people? In Gamyam, Abhiram and Seenu have a chance encounter with Seshu, a surrendered Naxalite. By sheer fate, they end up in the forest with Sheshu’s former comrades, who want to punish him for “viplava-droham,” “betrayal of the revolution.” Sheshu makes a dramatic speech about how they need to leave the forest, put down the gun, and be among the people and help them. Of course, this comes from an notion of Naxalites as a deluded army, confined to the forest with their guns and completely cut off from “real people.” But I think the Naxalites are just a red herring, a convenient stand-in. The actual deluded force hiding from the people, of course, are the rich—Abhiram’s ilk.

Before Abhiram embarks on his journey, Janaki makes visible to him what was previously inaccessible. At first, this only ends up solidifying their differences. He describes it as “labor, kullu, kampu”— “dirty areas” that he is disgusted by. “I did it all for you!” he shouts at her. He tries to placate her by saying that he understands her commitments: “you’re a social activist—” but she says “No—it’s not that. We’re different people.” Janaki refuses to be a savior-figure. She refuses to put on airs, even though the film sometimes props her up as a flawless empath. She never draws attention to herself through her actions, which she describes, simply, as “helping.” On the other hand, Abhiram puts on airs even when performing useless gestures, like when he throws his eight-thousand rupee jacket onto the homeless man. He is so cut off from the world that he does not even know how to help.

To be a savior, the people you have chosen to save need to be cast as always suffering. But the candidate best suited for the savior role in Gamyam—the rich man—is the one who is always suffering. All his comforts (the riches, the cars, the parties) cut him off. The safety of never having to get out of his car comes at the cost of his humanity. The film makes it clear that the very world that Abhiram is isolated from—usually portrayed as the world full of suffering people that must be saved (see Bharat Ane Nenu, 2018)—is also the world of connection. Or rather, a world that opens us up to the possibility of connection. Janaki knows that her patients are capable of much more than suffering: for her, they are equally a source of love and kindness.

3: Grounding the Prince

The ultimate disaster for the caste Hindu family is the fleeing of the prince, that is, the muddula koduku, the precious son. We learn from Ambedkar that the most dangerous form of this flight is inter-caste marriage. Abhiram’s father doesn’t have to worry about that: no character in Gamyam speaks the name of caste. But there is a flight here that, at first, still devastating to Abhiram’s industrialist father GK. The weakest scene of the film is when Abhiram’s father uses the mythical power of the police force to pluck him from his journey and meet him. Abhiram waxes eloquently about how he is finding himself as he travels, and suddenly the father is alright with it. GK notes that Abhiram is talking just like his mother (who has died in childbirth)—how convenient that Abhiram’s mother was also exactly like Janaki. In a matter of a few minutes and a few tears, the prince is allowed to “find his own way.” Abhiram’s exit is absorbed back into the Hindu family structure. Once he makes amends with his father, Abhiram’s flight becomes a temporary one.

Perhaps this is why the film must end with Abhiram and Janaki hugging each other at the Narsipatnam railway station. Why watch the two of them become part of GK’s household and reverse Abhiram’s transformation? Are the two of them really doomed to settle into his mansion together as the local Bill and Melinda Gates? And all of a sudden, the film’s intended stakes become clear. Suffering and all that be damned, the actual problem with Abhiram is that he hates the idea of parenthood. No wonder his main revelatory moment on the journey is when a baby is born (he quickly sets up a makeshift birthing room in a stall on the side of the road during an infamous ghat road traffic jam). With GK’s approval, Abhiram’s transformation becomes less about opening himself up to the world and more about slotting himself into the position of husband and father. Right back into the mansion to claim his rightful place on the throne and continue the family name.

So can we save Abhiram from himself, whatever the film’s intentions? Maybe the answer lies in perpetual flight. Can we imagine an Abhiram who flatly refuses to return home? An Abhiram who takes on board Janaki’s impulse against safety, and never makes amends with his father? I look to Gaali Seenu, who, as suggested by his name, is never grounded, never safe. Until the police forces him to answer, Seenu never tells anyone where he is actually from. “Manaki chaala oorlunnayi” (“I’m from a lot of places”), he always replies. In a strange way, he embodies Janaki’s ideals—whether he’s giving a lift to three little kids, teaching another kid to whistle, or cheekily offering gutka to a sassy grandmother. Conversely, he is most out of place when he meets Abhiram’s father, the safest and most grounded character in the film. They literally do not speak the same language: when GK tells Seenu to “take care of Abhiram,” in English, he has to seek out a translation. And his comedic gesture of wiping his hand before he shakes GK’s is an all too tragic reminder of his inability to relate to Abhiram-at-home.

Seenu must die in the end. It is almost as if his death warrant is signed as soon as GK asks him He is shot by police as they escape from the conference with the Naxalites. At the railway station, Janaki meets an Abhiram that bears the trappings of Seenu without the actual conditions of his openness. Gaali Seenu is no longer needed when Abhiram comes back on to familiar ground: he can only exist while Abhiram is in the air, on the road, in transit.

Seenu is a reminder that creating safe bubbles for ourselves impoverishes us, limiting our horizons, turning us into potential empty saviors. Allowing us to be articulate, charming, sexy voices against this or that. Or for this or that–little surprise that the voices of fundamentalism are often the most well-spoken. And speaking in these voices almost never entails giving anything up, or addressing the conditions of our privilege. In these cut-off spaces, we can only pretend at connection. This is the virus fueled by the privileged: the ones who will always put themselves first, at the cost of all others.

*

చాలా బాగా రాశావు గౌతమ్. ప్రౌడ్ ఆఫ్ యు – అమ్మ