Life is never easy in troubled places and times; so is art and its representation. The period from 1979 to 1984 was turbulent due to the Assam Agitation Movement which aimed to drive away the non-Assamese people from the state. Against the background of the Economic Liberalisation, the Assam Accord and the rise of United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), there crept a feeling of disenchantment and a sense of shattered ness among the poets. The failure of the Assam Accord led to fundamental or communal hatred, conflict, murder and continually increasing violence.

This fragmentary backdrop gave birth to several poets in Assam. The poetry of the 1980s was a departure from the poetry of the earlier decades which sang the magnificence of mythical heroes, love and peaceful nature. There emerged new voices from the tribal corners and a great influence of the Western poetry of symbolism, imagism and even magic realism was felt.

There were many reactions like ‘uncertainty, evil shades of consumerism, distrust of universalism, rejection of pre-determinism and a sense of cohesion, disbelief in ideology, distrust in the possibility of change in society – all leading to the fragmentary spirit of Assamese poetry.’ (Subhajit Bhadra, ACIELJ, Vol: 2, Issue-1, 2019).

Samir Tanti with his unique style gave voice to the tribal reflections and criticised the politics that took place resulting in anguish and desolation. He brought in the socialist and modernist poetry. Anupama Basumatary enriched Assamese poetry by bridging the gap between common people and poetry. Nilim Kumar, Anuvab Tulsi, Nabakanta Barua, and Bipul Jyothi Saikia – all these contributed to Assamese poetry portraying the diverse shades of life. Nilima Thakura Haq portrayed the evil tendencies of human beings and the evil effects of consumerism.

Lufta Hanum Selima Begum, Ajit Gogoi, Ganga Mohan Mili, Jeeban Naraha, Ajit Kumar Bordoloi, Utpal Bora, Mira Thakur and several others wrote about love, anguish about life and society.

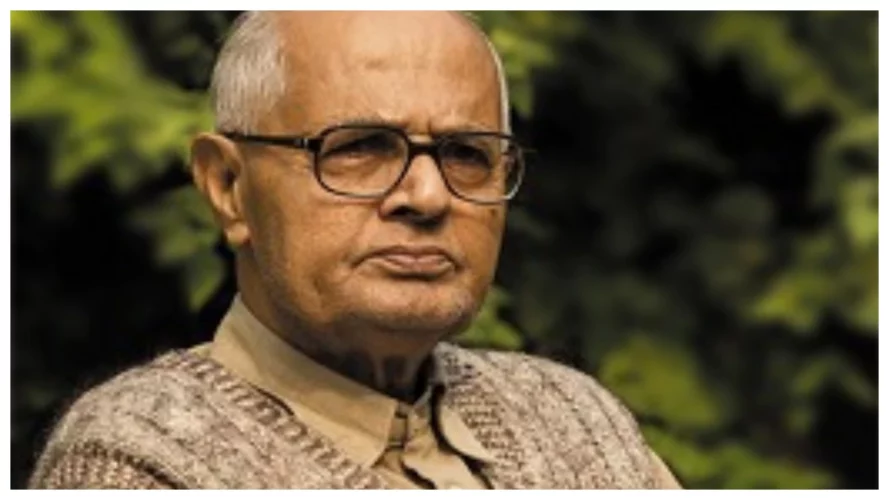

Born in 1933 and hailing from a small village Chakiyal near Dergaon in Assam, Nilmani Phookan (1933 – 2023) is always a poet who knows how to balance reactions and responses. A teacher by profession and an artist by nature, Nilmani Phookan with his thirteen volumes of poetry took the Assamese Muse to new heights with his symbolic and imagist styles.

Nilmani Phookan as a poet had his inspiration from his predecessors like Hem Barua, Amulya Barua, Maheswar Neog, Navakanta Barua and Ajit Barua, the poets that represented modernism during the early forties. He demands an equal place along with great poets like Jayanta Mahapatra, Keki N.Daruwala, Sanka Ghosh in modernist Indian poetry with his great works like Phuli Thoka Suryamukhi Phultor Phale (To a Sunflower in Bloom, 1972), Golapi Jamur Lagna (The Raspberry Moment, 1977); Kobita (Poems, 1980); Nrityarata Prithivi (Dancing Earth, 1985)

With his roots in the Assamese countryside and the rich heritage of tribal myth and folklore, Phookan imbibed the rhythms of village life to shape his sensibility. As a lecturer in the Arya Vidyapith College in Guwahathi (1964 -1992) he observed the turbulence of conflicts of the Assam state.

A very sensitive poet to the core, Nilmani Phookan responds to everything – either animate or inanimate in a very passionate way. His poetry is replete with images related to nature and human nature. Critics consider that his contribution to Assamese poetry is phenomenal in several ways. As observed by Arundhathi Subrahmanyam, who interviewed Phookan, we find

“… not merely a sage’s reflective detachment here, but urgency as well as anguish and a deep sense of loss. Most importantly, (to my mind,) the unapologetic preoccupation with the cosmic and existential does not lead to grandiosity or a resort to misty abstractions. For even while the poetry invokes generalities, it does not ignore the scorching particular that has always been such an integral part of the poet’s province.”

With a considerable influence from the French symbolists and Japanese imagist poets, Nilmani Phookan adds the aroma of folk life and folk culture to poetry. The poem Cutting your fingers of ferns (Muthi-Muthikoi Kati Tor Dhekiar Anguli) talks about the innocence of the poor women and the poet’s observation of every day details of pain:

Cutting your fingers of ferns in bundles

You sell them in the darkness of Ajara

Sister which village do you hail from

Do people there breathe their last

Do you plant the Akon in the mounds

Do you keep fish alive in the pond

Has your man

Returned home

Through the chinks in the walls

Do rivers rush in at the middle of the night

Sister in the skull of your kitchen

You save your days

With your wakeful eyes burn

The darkness of the Kanchan at the gateway

Sister which village do you hail from

Do you use henna on the splitting heart!

(* Ajara – a place near the air-port at Guwahati, * Akon – a small tree with long broad leaves one side of which are white in colour, * Kanchan – a flowering tree)

Nilmani Phookan was very balanced in his portrayal of the violent situations in Assam during the Assam Movement. He says:

“ ….

In my tears

the stars have soaked,

the grass drenched in blood over there

has soaked in my tears.

The overblown surujkanti flowers have not

wilted though they are to,

the Dichoi and Dibong have not

changed into ice though they are about to.

For days the moon has not

risen over Diroi Rangali.

…” (A Poem)

During the eighties, Phookan’s poetry gained more social consciousness. He exposed the disturbed soul of Nature’s serenity with the intervention of man’s violence. His poetry speaks about ‘the anguish and the joy of the living and the dead, the outcry that trundles down the road day and night, the desert sun for the meaning of death and the vacuity of living, the red patch between the lusty lips of maidens, the yellow butterflies with wings spread on barbed wires for the insects, the snails and the moss … and the mothers of five hundred million sick and starving children.” ( Poetry is for those who wouldn’t read)

Nilmani Phookan’s imagist soul makes nature and its objects speak a new language of poetry in surrealist terms –

“ I am a naked man Ageless with my whole body

I have felt some rocks hidden under water and earth

Some rocks and a planet made of human flesh and blood

My lips, tongue and innards have felt some rocks

In the angular privacy of my prolonged life

Some rocks horizontal vertical round.”

But Phookan never escapes from the facts of reality. He addressed social issues in a very conscious way. Though the diction is simple, it holds a new sense of urgency and intrinsic strength through its concrete yet metaphorical use of language. See the poem, ‘There’s a Meaning in Everything’ (Sakalu Kathare Eta Nohoi Eta Artha Thake):

There is a meaning, one or the other, in everything

For instance, in poems in love

Earth fire air water

In the barking of blind dogs

In a chirping insect

Inside the pocket of a blood-stained shirt

A meaning can be unearthed from everything

A meaning lies in the star upon each finger-tip

Of the framer of meanings

The games of meanings go on

As the children’s games of noughts and crosses

The wounded words seek

A voice of flesh and blood

The madness of lovers and poets goes on

The sobbing leaves of the evening

Yearn for the salty touch of a tongue

A searing lamp burns upon the palm

Of an anonymous old woman

O’ compassionate speaker

Deliver one more meaning

That this oppressed has been deprived of

(Translated into English by Krishna Dulal Barua)

Phookan’s treatment of nature and its colours brings to our mind the poetry of Garcia Lorca whose poetry shines with a novel texture.

As observed by Dr. M.Kalamuddin Ahmed,

“The poem Hothat sei artanad ahi (Suddenly that scream coming) focuses on red colour; the main concern of the poem “Ei etai matro sobdo seujiya” (This lone word — Green) is greenery, and in the poem “Kin kin henguliyar majot” (In the drizzly glow) yellowish colour enriches the theme.”

The poem Sunset across the Brahmaputra (Brahmaputrat Surjyasta) stands as an example for this:

The day’s golden vase of the heart

Dropped from the hands of emptiness

It dropped silently

And sank

In the bubbles surfaced

The red pledge of the vase –

Its glaze heart-rending

What a flare

Of man’s final covetousness

Now each spectator has returned

With the relapse of the same rheumatism

Down the smoke and dark blue storeys descended

Emptiness itself

Emptiness of the heart

(Translated into English by Krishna Dulal Barua)

If poems like Nrityarota Prithivi (The Dancing Earth) display his use of colloquialism, the language of poems based on silence namely “Dhonwar somoy” (When smoke rises), “Eta nil upalabdhi” (A feeling of Blues) and “Artoswar” (Scream) keep away from the colloquialism.

His language of the latest poetry collection Alop Agote ami ki kotha pati Achhilo (What were we talking about just now) is marked by a rare density. The poet observes the universe, time and his surroundings very keenly and the poet throws light on the inner soul of man. The images of the moon, stars and sun come up in these poems with a deeper and more complex dimension. The poet observes various incidents where humanity is humiliated, and he portrays them with both harshness and tenderness.

Come let’s go out (Ahok Ulai Jao)

Come let’s go out. It’s terrible. Nobody had believed. Any moment

there could be suffocation. Blood showers as rain. None can tell before

the hour of death. Kartavirjya’s hands number a thousand. The man

beheld by him in his mirror is a spectre. My deceased father looks

for me now and then. Noni!

This great poet too had to face undue criticism from his jealous contemporaries who alleged that Phookan copied ideas from a French symbolist poet. It was later proved that they translated Phookan’s poems into English in the name of a French poet and tried to bring a stain on his career as a poet.

But can someone control the magnificent buoyancy of a myriad-coloured rainbow? No!

Nilmani Phookan proved his mettle as a poet and is acclaimed worldwide as the poet that brought elegance and enchantment to Assamese Poetry. We do not find the depth and complexity of Nilmani Phookan’s poetry in any of the poets of his times. He controls his emotional overflow with his wisdom and insightful maturity. It is observed that the sadness in Phookan’s poetry is akin to that of the German poet Paul Celan and we can see several shades of Japanese poetry with its Zen serenity. The poet is confident of drinking the sap of life out of sadness.

His presence is sage-like, canvas-vast, imagination-mythopoeic and voice-bardic. He dealt with many binaries – ‘epic and elemental, fire and water, planet and star, forest and desert, man and rock, time and space, war and peace, and life and death.’ Phookan, one of the outstanding poets of the post-war period, reached the highest pinnacles of fame with his Sahitya Akademi Award, Jnanpith Award and even Padma Sree.

*

Add comment