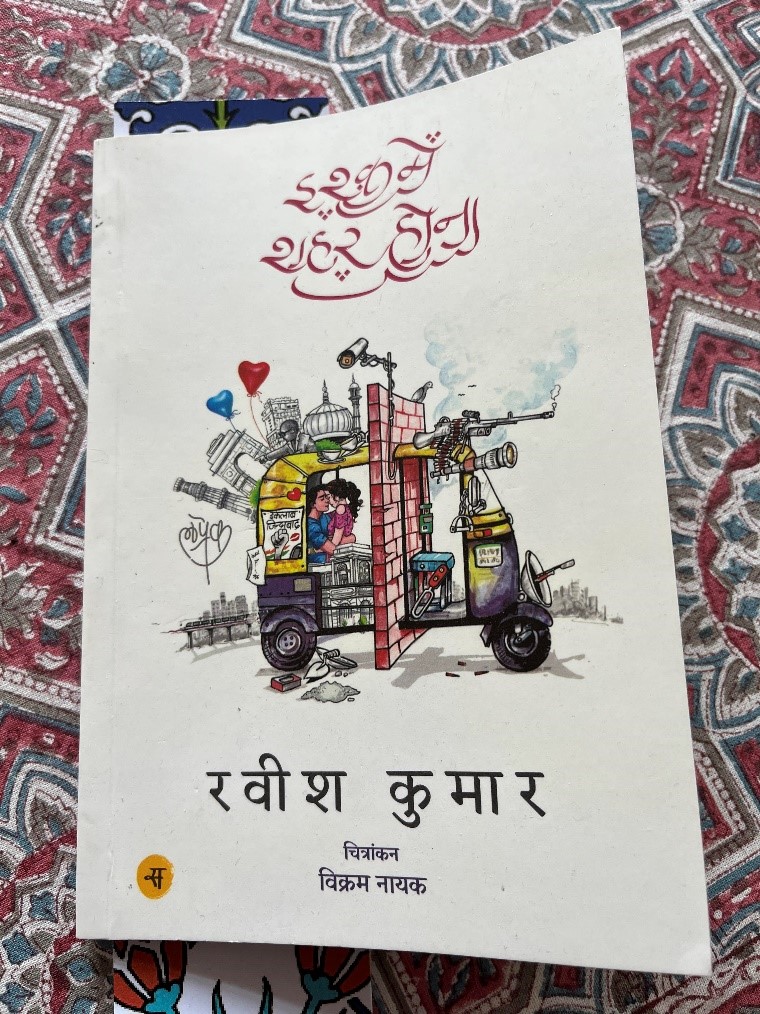

I was eagerly awaiting the Laprek trilogy (Laghu Prem Katha – or small love story), a micro-fiction enterprise written in Hindi. I finally laid my hands on the first of these series in Delhi, titled Ishq mein shahar hona. Published in 2015, Ishq mein shahar hona as the first part of Laprek became initiated by NDTV journalist Ravish Kumar (also recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2019) and the micro-fiction used to first appear on Facebook and Twitter. This micro-fiction is now published in the form of small books, brought out by Rajkamal Prakashan where anecdotal prose about everyday life and love in Delhi is poignantly illustrated by Vikram Nayak.

As already indicated, Laprek is organized in three books, and while only the first is authored by Ravish, the second named Ishq mein maati sona (the soil turns to gold in love) is by Girindra Nath Jha, and the third Ishq koi news nahi (love is nothing new) is by Vineet Kumar. Being interested in modern Hindi prose written in and about Delhi from a migrant’s perspective, I was eager to read Ishq mein shahar, which has recently also been translated into English under the name A city happens! I felt unimpressed by the English title, since it felt inadequate and unable to express the subversiveness concealed within the Hindi original. The predictability of falling in love in the city—Shahar mein ishq hona is reversed in the original title, to express how we become the city through being in love, encased within its everyday topographies. Perhaps an adequate translation of the title would read better as Becoming the city, in love!

Ishq mein shahar is a lilting book of many poetic anecdotes written in prose that are about feeling like the city, contextualized by two separate introductions. These introductions apart, Ravish’s anecdotal prose about the city—about Delhi, about being, becoming and feeling like Delhi, as a way of feeling love, is the most transformative I have ever encountered. For example, he writes (page 21):

Today I feel very small town…

And today, I feel very metro…

Yes, when you are passing South Ex, I feel I am Karawal Nagar

Keep quiet! You are mad! In Delhi, everyone is Delhi.

No! Everyone in Delhi is not ‘Delhi’. Not everyone’s eyes show love!

Alright! So how did I become South Ex?

Just like I became Karawal Nagar!

You are right…

Without Barapulla Highway, how would the distance between South Ex and Sarai Kale Khan grow small?

Do you love me, or the city?

I love the city, because you are my city.

In his two introductions, Ravish introspects on the revolutionary nature of love in the city that crosses boundaries of caste, community, language, religion and culture—a true revolution from the inside, with far many more implications than freedom from colonizers. And it is exactly this revolutionary love today that is under political siege. Lovers are arrested today for this revolution, denigrated in ways that even the Shakespearian epithet ‘Romeo’ has become an abuse. Ravish writes (page 81):

Why does that man in a blue coat stand there clutching a book to his chest? She was especially habituated to inanities in moments of their love-making and so he kept silent. Continuing to run his fingers through her hair, their breaths rose and fell in unison, traversed the air that was freed for them to breathe in, created by Ambedkar. You will see! One day, it is that very book he clutches, that will unite us forever!

Ravish describes his initial explorations of Delhi and about how he traversed new localities to understand the chaos that made Delhi in the instance when he saw how bras were made. Ravish writes (page 18):

I went to a locality nearby to Bhajanpura one afternoon, and saw hundreds of hands busy making bras (women’s undergarments). Seeing towers of bras was an experience that felt like coming outside from the inside. I felt so scared that I ran. I returned another afternoon. I had seen lines for kites being made. I had seen the steel made at the Tata steel plant in Jamshedpur. Even bras are made. Everyone should go and see how bras are made. In our youth, we make the mistake of searching for the female body in the bra. But the liberation of seeing cloth as cloth takes place only when you see clothes being made. It is this that transported me from searching for Delhi in books, to searching for Delhi in people.

The story about bras being made is a powerful metaphor about the making of Delhi, by the many who found love in the city. So moved was I by Ishq mein shahar, that I decided to make some micro-fiction of my own that described how the home was a place of recreated love, and not a passive shell where love was housed. My husband and I have different ways of loading our dishwasher, and he hates the way in which I do it. Today when I loaded the dishwasher, he said:

Again, you have kept the dishes in that way

But I like keeping it that way

But it is not right…

It feels right to me…

Then you unload the dishwasher when the dishes are done!

Not too much love over there in the conventional sense, but full of it, seen from the Ravish-ian lens—Ishq mein ghar hona!

*

Add comment