Gora, A novel in Bengali by Rabindranath Tagore: Telugu Translation by Sivasankara Swamy (Tallavajjhala Sivasankara Sastry); Sahitya Academy, New Delhi, 3rd edition 2002; First published in 1961

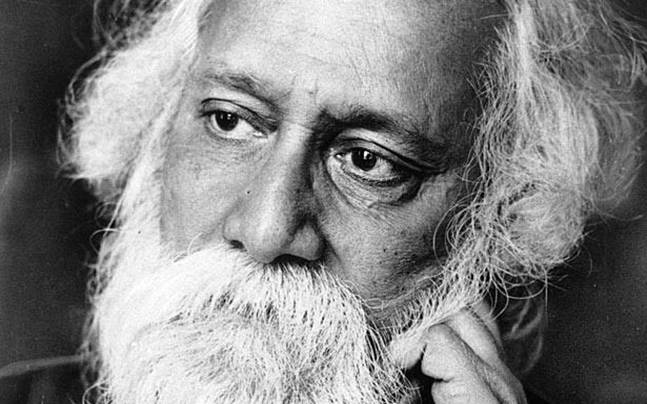

Rabindranath Tagore is perhaps the most celebrated writer in Bengali in British India’s who was awarded Nobel prize for literature in 1930, first of its kind, not just in India then, but in the whole of Asia. Tagore was many things rolled into one – a poet, a short story writer, a novelist, a music composer, a creator of what we today call Rabindra Sangeet, a playwright and an educationist who successfully established Viswabharathi University at Shanti Niketan. Born in Calcutta (now Kolkata) on May7, 1861 Tagore breathed his last at the ripe old age of eighty on August 7, 1941. For all his life, he lived in British India. In the times and the contexts that he wrote, the perspectives were so totally different from what they are today that contemporary India cannot easily relate to some of his writings.

Historically, India was under British rule for close to two centuries. Before that, for more than a millennium, Indian race was politically, socially economically and culturally under suppression and witnessed a that backwardness that was considered dark age in India’s history and this attracted the ridicule and exploitation of political masters constantly for seven to eight centuries. There were two schools of thought in Tagore’s time. One group of orthodox Indians, proud of their heritage and ancient cultural and civilizational advancement as compared to the then west refused to change according to the changing needs of times. India was bogged down by the some of the social practices that marked the entire native race as barbarians by the Europeans whose scientific temper always placed them on higher plane in terms of modern knowledge and belief system. With the rule of Mughals in India and the entry of Islam into India, the already prevalent offshoots from Hinduism like Buddhism and Jainism made India into a pluralistic society. On one hand Indian aristocrats in Bengal admired the European culture to such a great extent that intellectuals like Michel Madhusudan Dutt, Govind Chader Dutt and his daughters Toru and Aru Dutt took to Christianity. Upper caste conversions in India, especially in Bengal, paved the way for the Bengal’s bhadralok to cross the seas and reach the shores of Great Britain. They were fascinated by the language, literature and culture of the great English poets, who wrote under the influence of the ideals of French Revolution such as liberty, equality and fraternity. The British rule thus opened a new cultural window to the west and for some of these Indian intellectuals, native languages became butler languages. On the other hand, there were social reformers and moderates like Raja Ram Momohan Roy, who while strongly retaining the cultural heritage of India, fought for a reformist movement in Bengal. Schools and colleges began to be opened for girls. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Keshav Chandra Sen were some of the popular names who fought for the abolition of practices like Sati in Indian society. English education was introduced in Indian educational institutions in erstwhile Madras state and in Presidency College, Calcutta.

Tagore grew up as a child of nature and wrote on the lines of India’s Bhakti and Sufi traditions of middle ages. His concept of nationalism was one without borders and that of universal brotherhood, based on the principles of Vasudaiva Kutumbakam. These concepts were introduced to the West for the first time. At the same time, he admired whatever was best in the West’s intellectual traditions. Tagore’s ideas on nationalism without borders, humanism as a wider desirable concept began to influence many. His liberal and secular ideas in the context of India’s multi-cultural fabric had the first seeds sown in our literatures by Tagore’s vision of Universal God and Universal man. A God who can be seen in a rain drop, in a blade of grass, in a flowing river, in a roaring sea, in a chattering bird and mammoth nature and a man whose identity belongs to the world at large, touched the heart of many lovers of literature and poetry. He dreamt of and sought a world of freedom which can widen the horizons of our universe. So totally utopian some said, but it still remains a distant yet solid dream for many in India. He gave India a vision and a distinct voice through his writings. It is said that when he got up early morning to sit still in his garden, communing with nature, the birds mistaking him to a be statue perched on his shoulders. It is also said when he walked on any foreign soil in his long robes and flowing white beard people remembered the image of Jesus Christ.

Home and the World and Gora were two of his well-known novels which besides being translated into various Indian languages were made into successful films in Bengali. But Tagore’s Gora is the one book by which he is still remembered in India. It was published in 1910 and was translated into Telugu by a scholar of yesteryears Sri Tallavjjhala Sivasankara Sastry, later known as Sivasankara Swamy. His Telugu translation of Gora was published by Sahitya academy in 1961. This copy was a third edition. I first read Gora in English translation. I must say my memory of the first reading was very clearly smooth and fast moving. This Telugu version I read recently was more of challenge as the style was very traditional. Though it did justice to the story, the running was not as smooth. This review makes an attempt to review the novel Gora in the framework of Tagore’s ideas on nationalism, religion and the related identity and establish how Tagore validates his vision of freedom in this unique story. Gora initially starts as the story of two friends Gaurmohan (Gora) and Vinaybabu, who were temperamentally opposite but were close friends since childhood. Gora was very rigid in his beliefs and his love of what he considered was his land, its culture and his religion and rituals. He never ate with people who violated the dharma of their caste or religion. He never ate with his friend Vinay also as he believed that he did not follow the tenets of his religion. He differed with his own father in matters of faith. Vinaybabu greatly loved his friend and considered him his Guru. Gora’s mother considered Vinay as her own son and he too called her mother and often ate when she offered to serve him food which was always objected to by Gora. The story opens with Vinaybabu accidentally meeting the family of old Pareshbabu as he and his daughter Sucharita met with a small accident in front of his house. He helped them reach home safely and started visiting them regularly afterwards. Pareshbabu had three daughters Sucharita, Lavanya and Lalitha and one young son Satish. The girls were brought up in a liberal household and did not observe any purdah as was the custom. They moved freely in society which was not appreciated by contemporary conservative society of Calcutta in those days. His proximity to the girls and his frequent visits to Pareshbabu’s house were resented by Gora. He did everything he could to stop Vinay from visiting the family. He even makes a courtesy call to Pareshbabu, who is a soft-spoken gentleman. He nurtured his daughters as sensitive, liberal-minded free spirits. When Gora visited their house, they thought he was loud, rude and very opinionated. He commented about those who followed the west blindly and did not consider it their patriotic duty to defend India and its faith. The rift between the friends continued but now and then both of them made efforts to patch up their quarrels. Vinay was often embarrassed by Gora’s rigidity and argumentative authoritarian nature. But during one such argument Gora felt one spark of attraction towards Sucharita. His attitude towards her starts melting. But he tries to resist his attraction and leaves his home and village to self-examine his life and his views. He maintains his distance and gradually moves away to such an extent that he decides to renounce the world and take up sanyas. When he was about into his new phase of life, he comes to know of his father’s illness. He rushes to home to meet his father. His father Krishnadayalbabu, an affectionate and generous human being reveals to him that Gora was not his own son biologically. He told him that Gora’s father was an Irish military officer who was killed in a conflict and his mother took shelter in their house for one night and she died after giving birth to him in their house. As there was no option, they adopted him and brought him up in their home. The world turns upside down for Gora. Whatever he thought was his till yesterday was no longer belonged to him-, his mother, motherland, his religion, caste and all his beliefs which made his nature and personality turned topsy-turvey. This was the master stroke that Tagore chose in Gora; to establish the meaninglessness of identity and belief. These man-made ideals hold no real sway on an individual. But his ideas he held for his life would not and could not totally vanish and the only option for Gora was to open his horizon and expand his vision of God and mother and motherland to encompass larger humanity. He comes back to life and offers his hand to Sucharita to start his life’s journey with her and she willingly accepts. Vinay also gets his best friend’s approval to make his choices according to his beliefs. The narrow domestic walls were thus broken and reason takes the place of blind belief. Agha Shahid Ali, a Kashmiri American poet of modern times reiterates the same point when he says he lost faith in his God and the domes of his faith shattered when his footwear was stolen from outside the mosque. But when the dome of his faith shattered the vast sky opens up before him and his vision becomes broader.

Gora thus remains a novel to be remembered in India’s literary journey as it opened a new door for Indians, as well as the west, about the all-inclusive nature of India’s plurality, even before the constitution of India made an attempt to set the historical errors right.

*

A balanced introduction of Bengali culture and the growth of Rabindranath as literary person who ultimately gets Noble in literature.

Syamala garu has reviewed the novel Goara quite well. The way she narrated the story resembles some of the Telugu novels which ends all very happily like Gora did.