Nothing was distinctive about ash, nothing intimate about its appearance. It effaced all notions of personal history in one blazing flash.

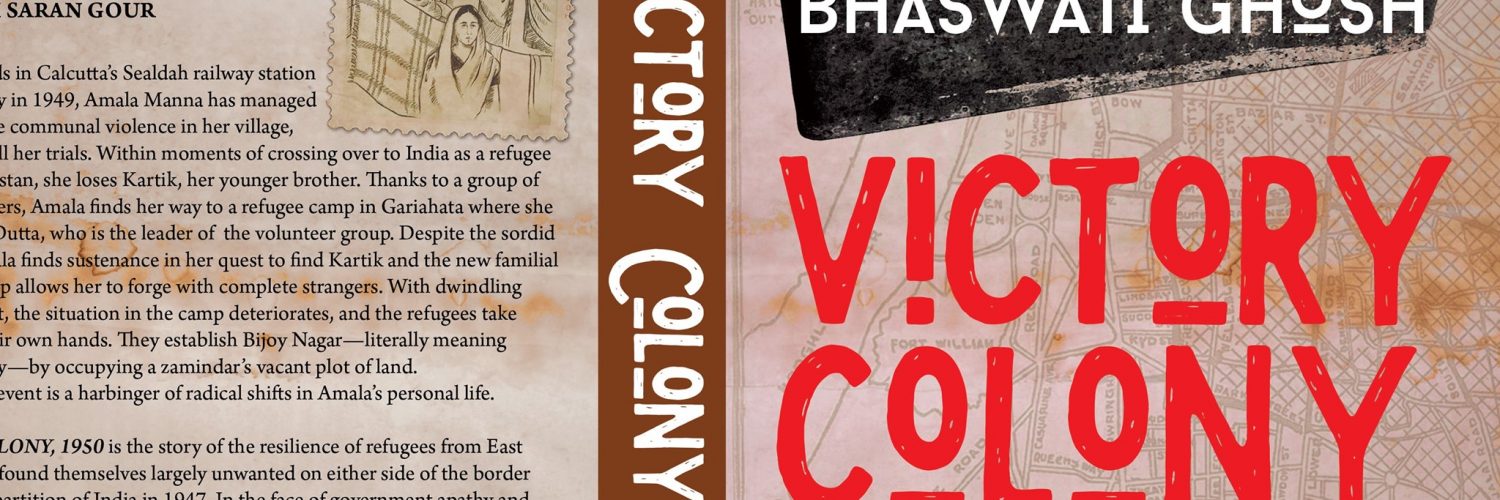

The above lines, from Bhaswati Ghosh’s debut novel, Victory Colony, 1950, sets the backdrop of the narrative, where the lives of its two main protagonists, Amala and Manas, are forged together by flames of the partition of the Indian subcontinent.

Amala, a young refugee from Barisal, now East Pakistan, loses contact with her brother almost immediately after they arrive in Sealdah Station. Manas, one of the volunteers helping the refugees, bring her to a makeshift camp in the suburbs of South Calcutta. As Amala tries to build a new life far away from her village, the scars of the accidental death of her parents and the violence of a raging mob still fresh in her memory, Manas – erudite, rebellious, bourgeois – gets irrevocably drawn towards the centre of her world.

Soon the government’s support for the camp starts to dwindle, leaving Manas and his friends searching for other options to help the refugees. Chitra, an aunt of one of the volunteers, agrees to help them by starting a sewing workshop at the camp. The disillusionment of people at the camp increases when a young girl from there was raped near Sealdah Station. Amala and her friends, in an act of rebellion, forcibly take over the land of a local zamindar and set up a colony for themselves – naming it Victory Colony. As they start to reconfigure their lives and livelihood in Victory Colony, Manas proposes to marry Amala. The story follows their uncertain journey as Manas and Amala, like history itself, tries to heal their wounds and find their footing in a city still coming to terms with the human cost of the partition. The plot is engaging throughout, with the possible exception of Amala’s reunion with her brother, which seemed like a Dickensian coincidence.

Despite the grim, existential backdrop of the partition, the novel brings to life the true spirit of humanism and resilience which kept the hopes of the characters alive. The small acts of kindness – Firdous Chachi and her husband protecting Amala and her brother in their village in East Pakistan and helping them with a safe passage to Calcutta, Chitra Mashi helping the girls at the camp to take their first step towards financial independence, Manas and his friends working relentlessly to improve lives of people at the camp – were chronicled with the love and perfection of a miniaturist. Together, these acts try to stitch back the torn canvas of a city with tenderness and care.

The timing of the novel couldn’t have been more topical. As the rise of intolerance and divisive political propaganda is pushing India and many other countries around the world to crossroads, we need more stories such as this to help us look back through the prism of history and learn from the fault lines of our past.

*

[…] ~ Siddhartha Banerjee, Saaranga […]