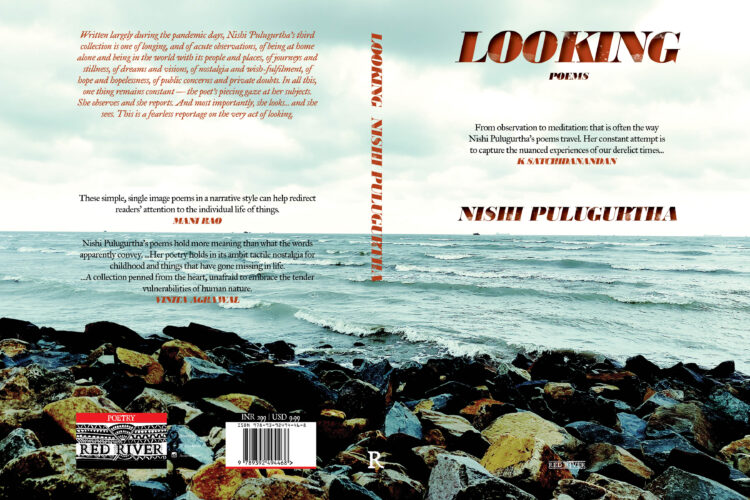

Nishi Pulugurtha is an associate professor in the English Department at Brahmananda Keshab Chandra College in Kolkata. She is an academic and an Indian poet who writes travel blogs, short stories, poems, and creative essays on Alzheimer’s. Her third volume of poetry, Looking, has recently been published by Red River. In Looking, she compiles her single-image poems to portray the poignant connections of journeys from the bustling train stations to the contrasting landscapes of busyness and serenity, echoing the haunting solitude of unheard voices.

In the first segment of the book, “And They Tell Tales”, the poem “The Station Building” initiates the anthology with an explicit description of “a huge red building,” invoking a sense of serendipity. It records the cacophony of the red station building that beseeches remembrances of “journeys made” and “journeys to be made,” in anticipation of “nice, happy times.” The poet concedes “the very sight of it, charms,” expressing her ineffable, abiding affinity towards this station building, which symbolically exudes a sense of belonging, further emphasized by the phrase “It always had.”

The second poem, “The Journey,” accounts for a haphazard yet thoroughly cherished train journey. Amidst the hurly-burly of the bustling train station, she embarks on a journey with fellow passengers to reach a destination unspecified. It metaphorically represents a journey through the uncertainties of the future, which assimilates the poet with the unknown passengers: “the train that will take us along.” She elucidates how everyone strives not to ‘miss’ the train, as the departure time is prefixed and no one wishes to lag in chasing a destination, an anchor. This sense of urgency reflects the apprehension of missing a train—an opportunity to venture out into unexplored paths. It also casts light on the passengers’ perception of individual purposes in life, as they are all headed in the same direction yet everyone has their own goals to pursue.

Adding to this quintessence of pluralism, in the poem “The Ghat”, the poet captures through the lens the spectacle of a humdrum ‘Ghat’ in Bengal. Shifting the setting from the busy red station to this mundane ghat, the poet adds to her montage a new shot of a serene and languid Bengal ghat to fine-tune the contrast of her composition. From a vantage point, the poet observes, as an ardent photographer, how the dogs scurry around and the little bird flies in harmony to some distant height, a peaceful backdrop contrasting the hasty ambience of the station building. It captures the movements in leisure of the dogs, the little bird, and the indifferent passersby, while the poet catches them in action. Through these poems, the poet has envisioned individuals setting out on new journeys to their unpremeditated destinations while making memories with fellow passengers on the journey.

The poem “Pauses”, expands on the occasional hiatuses in life, allowing people to reflect on the past actions metaphorically implied by the “broken pieces of glass, littered, left.” These poems shed light on the passage of time as well, which brings opportunities for new adventures, introspection, and epiphanies that lead us to our destinations.

The second segment of the anthology comprises poems like “The Morning Glory Plant”, “Yellow” and “Little Girl on the Terrace”. In the poem “The Morning Glory Plant”, the poet highlights the beauty of life reflected through small things, as in the Morning Glory plant hanging against “a green mossy wall.” The poet captures all such nuances that make life what it is, like a devoted photojournalist justifying the title “Looking” of this segment and the anthology per se. “Little Girl on the Terrace” is a poem that reflects the emotional connection between a father and daughter and reminds the poet of her relationship with her father. The line “It takes me back to another time, Daddy and I” implies how much she grieves the loss of her father and yearns for the bygone days of her childhood.

The third part of this book is named “Unheard Voices,” in which the poet records the anodyne notes of solitude. For example, in the poem “What Do I Do”, the poet asks “I need to do something; What is it that I want to do?”. This line epitomizes the sheer purposelessness and ennui of a post-modern being. After living a life filled with possibilities and achievements, individuals get stuck at certain critical junctures where they lack any foresight into their future endeavours and their outcomes. The following lines echo the existential angst of the poet:

“I look at the thing in my hand

I kept standing

I do not know what to do”

In the poem “Bhaskar”, she portrayed the introspection of a little child named Bhaskar, whose “question was never answered” as to why Bhaskar was Bhaskar and not Bhanupriya, even though “Bhanupriya was a better name” for the child. The poet reiterates that Bhaskar grew up to be ‘different,’ presumably reluctant to fit into the coordinates of the gender binary, quite like his name. The recurrence of lines such as “No one bothered” and “No one paid attention” underlines the topic of neglect and apathy. The poet underscores the reality that society suppresses the voices of those who break norms and cannot shape themselves as per societal standards. Reverberating the sentiments expressed in the poem “Bhaskar”: “Scolded, chided, ridiculed, Bhaskar learnt to keep quiet,” the poet adeptly delves into various experiences and injustices of life, capturing their essence like an ardent photographer. However, despite the profound impact of these narratives, the poet remains plagued by a sense of helplessness, conceding, “I do not know what to do.” This poignant admission underscores the poet’s ennui at the inability to impact tangible change in a world marred by neglect and apathy.

*

Add comment