It was usual for my parents to send me to accompany friends and relatives visiting us in Delhi. Delhi was an attractive tourist destination during the winter months, and though my parents loved having friends over, they were very busy. So, I was sent off with our guests to act as their tourist guide. We lived in the Northern part of Delhi, and I remember a childhood well spent at nearby places, wandering around Red Fort, visiting the India Gate, the Firoz Shah Kotla, and various Museums. Our guests shopped in Old Delhi, and in Janpath; they bought me pretty gifts, and we ate at swanky restaurants in Connaught Place. I loved these excursions. My parents never let us wander too far from home, afraid, we would get lost in the tremendous maze that was Delhi.

I must have been eight or nine years old when I first accompanied our guests to Qutub Minar. Though I had seen pictures of the Qutub Minar in guide-books, the variety that had folding maps tucked away inside, I was yet to see its magnificence with my own eyes. Earlier, people had been allowed to climb to the first floor of the Minar, and I had seen a black-and-white film song where Dev Anand and his romantic interest were filmed frolicking around inside, on the Minar staircase. But the higher floors were barred, because being very old, the construction was unstable. But this had now stopped, because of a terrible accident, a stampede on the staircase in 1981 that had killed 45 people, mostly school children. Qutub Minar, it was also said, had been built, embellished, and added to by the different Sultans of Delhi, and while the original Minar had consisted of seven stories, lightening had struck it down, leaving only five stories intact – or so tourist guides said.

On this occasion, the experience of seeing the Qutub Minar for the first time, flabbergasted me. Its grandeur, enormity, and beauty almost brought tears to my eyes, and I trembled inside my heart, as I stood close to it. I hugged it, stroked the stone, tried to listen to the stone, smelled the fluted cornices, laid my cheek against it, and looked up at the Minar from all possible angles. When one stood at the base of the Minar and looked up, the Minar didn’t disappear vertically out of sight as one would expect. Instead, it was as if the whole Minar could be seen from its base, as if it were bending over, to look back at the person looking up. My father said it was an optical illusion, or something I had imagined, in my desire to grasp the Minar in its entirety: look at it, and at the same time stand next to it and touch it. The fluted cornices with carved inscriptions were as clear and sharp as if they were made yesterday, and the Minar just standing there – huge, unapologetic, and monumental, suddenly became a reality – like beholding a giant wrestler standing there, feet firmly planted. It was not a picture, or a story about giants. It was real, and a magnificent giant. I knew in my heart even at the time, that I was indeed beholding something unique, and solemn. I was to see many Sultanate and Mughal monuments thereafter, but few had a place in my heart, as central as the Qutub Minar. Its beauty superseded everything I later beheld. Even the Taj paled!

That day went by in a whirl. I ran about the place utterly absorbed, lost to everyday life, humming introspectively under my breath. I touched everything I encountered – but at every instance I also kept looking at the Minar from different angles, and vantage points – from the courtyard, from between the arches, and from everywhere else that was crumbling, but was still alive and vibrant – the stones warm to the touch. I was afraid that if I stopped checking on the Minar, it would disappear, as if I had never really seen it, and only imagined it. It was as if I was memorizing its reality by looking at it repeatedly.

People were milling around in the courtyard, where there was a Gupta pillar, loosely called the Ashok Stambha back then. It was an iron pillar made from such pure material, that it was incorruptible to rust. Tourists who visited the Qutub Minar tried to embrace the Stambha from behind, since being able to do so was a sign of having long arms – a sign of greatness, evidenced in Sri Rama, or the Buddha. I became interested in two enormous cenotaphs that were in the courtyard, flanking the Stambha. I inspected these in detail, taking care to keep an eye on the Minar at all times, so that it wouldn’t escape, and I wouldn’t somehow forget it.

It was a similar feeling at the tomb of Allah-ud-din-Khilji. One entered suddenly into another domain, a different realm – a cool, gracious, and splendid interior of marble and sandstone. A young boy with a skull cap, about five years older to me, was sitting in a corner and reading, and chanting aloud from a booklet, as he rocked on his haunches. As I approached, he became startled and halted. But when he saw me, he threw me a scornful glance and resumed. He had bright blue eyes, and his gaze was so piercing, and sharp, that it shocked me. It was as if I had intruded into a world that was familiar, a world he knew, but that was as yet, foreign to me.

Running around that day from building to building, plunged into an ancient world, only superficially claimed by archaeologists, I deeply sensed another world lurking underneath it, that was older than the archaeologists, and had a different meaning – a meaning recognized by the scornful blue-eyed boy. As the boy resumed, I became spellbound by his language and music. I did not know this language, and his chanting sounded different from anything I had ever heard. This language was part of that otherworldliness I sensed, that would forever remain outside the grasp of archaeologists.

A child from a protected family, studying in the fourth standard, nothing else had troubled me more till then but the metric system. But this new world of enormous, and magnificent crumbling, gorgeous, ancient facades full of meaning, written over with a script that looked emblazoned and molten on stone, with grass growing on every flagstone path, pillar, and cupola, the slanting winter sun rays on it full of hectic specs, transported me to another planet, where reality was forever altered. Once there, and having seen, touched, felt, and experienced that reality, the world of metric systems would become banal, and even more boring than it already was. Our guests, though we had all set off jauntily in the morning, looked awkward as they wandered around like tentative strangers, afraid to touch anything.

There was another, smaller, shaded courtyard behind the Ashok Stambha courtyard. This octagonal courtyard, contained yet another giant cenotaph – the tomb of Sultan Altamash, who had built a massive part of the Qutub Minar. I was to later read that Altamash was better spelled and pronounced as Iltutmish. But that day, when the tourist guides pointed at the courtyard, they called him Altamash the great, one of the mightiest Sultans of Delhi, his daughter Razia Sultan another illustrious queen. I have since dismissed ‘Iltutmish’ as a new-fangled puritanical correction, and instead remained steadfast to the more intimate, and mysterious Altamash that I beheld that day. A new film had just been released on the life of Razia Sultan, with Hema Malini playing Razia’s role. My mother said that it was a poignant love story, which disappointingly enough, did not mention the Qutub Minar.

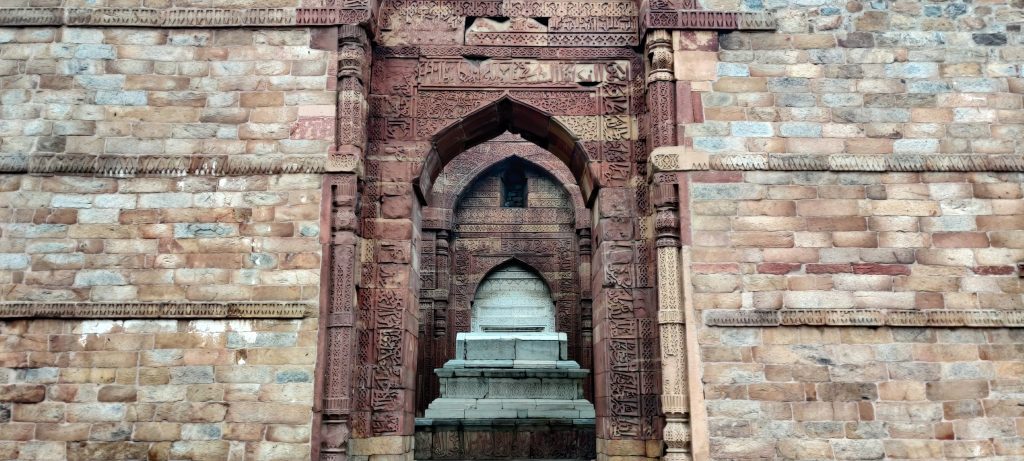

The small courtyard, as we entered it, was intricately carved, and breathtakingly beautiful, its sandstone surfaces inlayed with marble. Not only was its beauty utterly pristine and undisturbed, but the crumbling edifices surrounding it, only enhanced the haunting beauty of its carved interiors, that had a large cenotaph in intricately-carved white stone, placed squarely at its centre. Though the cenotaph was imposing, it did not dominate the delicate space around it – it was a perfect balance. The octagonal courtyard was open to the sky, allowing the afternoon slanting rays to fall on the far side, on a wall from which a small trailing tendril sported two or three snow white flowers. Perhaps it was that light, falling on that wall everyday, that had encouraged the flowers to bloom. When I turned, I could see the Qutub Minar looking at Altamash from a distance, and I wondered what the Minar thought, looking down at Altamash – its own builder – the creation looking at its creator.

I realized with an almost physical twist that the blue-eyed boy had entered the courtyard, and that he was accompanied by a group of others, preparing to sit on the floor, facing the cenotaph. Our guests, perhaps alienated by then, wanted to leave. But I suddenly felt as if I would die if I did not stay just a while longer. A small gathering of singers, harmonium, and tabla players struck up a song in jarring, high-pitched voices. The sound of it transfixed me. The language was only half known to me – nothing like that was ever played on Akashwani or Doordarshan. I could make out the words vaguely – they were in Hindi. But these words also became changed and un-Hindi, when intertwined with unknown, other words that I did not understand. It resulted in a half-understanding of an elusive world, perennially out of one’s grasp – as if one were looking at the world through billowing mist. I understood that the songs communicated a plea, directed at the cenotaph. But again, I was not sure. These pleas were also not directed at the cenotaph. They were directed at something larger, something greater than the Minar, and everything else the courtyards contained. It was difficult to understand, for the plea was not just plaintive; but demanding, celebratory, passionate, angry, and sad, all at once. And yet, despite what I understood, my understanding was partial. There was a deeper sonorous meaning that lurked underneath it all, and all I could do, was to swim around its edges.

The singing men looked haggard. They sang song after song at the top of their voices in their sharply melodious, slightly off-key, harsh voices, egged on by others sitting in the circle, who were clapping along, and breaking out occasionally in shouts of encouragement. And slowly, even as my guests shifted uncomfortably, looked at their watches, and then pointedly at me, the singing reached a crescendo. I did not exactly know when a certain line had been crossed, but I definitely understood at one point, that this was no longer just singing. My guests and the other spectators also stood transfixed, while the sharp golden evening light set the walls and cenotaph of Altamash ablaze. The singers and players who had been clapping, now began rocking back and forth in unison, their clapping becoming frenzied, the blue-eyed boy among them. And then, suddenly I felt that the rocking, singing group merged with the music and its language. The music now suddenly came from everywhere all at once: the walls, the cenotaph, us – the listeners, the tufts of grass blowing in the winter breeze. The dilapidation and ruins surrounding us came alive, becoming one with that music, the Qutub Minar at a distance a part of it all.

At this point, the blue-eyed boy jumped up to the middle of the semi-circle. He had been singing and clapping like the others. But now, he faced the cenotaph, as everyone watched in surprised anticipation. Singing in a thin, half-cracked voice, he began to swivel round himself, as if twirling like a top in slow motion. Soon, he gathered speed, and his cap fell to the ground, his kurta flying and flapping around him. His bare feet always at an angle, he began turning around faster, his twirling gathering speed. Soon, his face was a blur, and he seemed to be held by a force that pierced his very centre of gravity. His head rocked back with the speed, and his arms flew, as he was jerked round and round by an external, invisible force, a phantom merry-go-round. But the singing did not abate. If anything, it became wilder, sounding like collective keening now. I tried to look at the boy’s face, but he was unrecognizable – a lifeless rag doll with glazed eyes, twirling like a top, his arms flailing, his feet hardly touching the ground.

And just when I thought he would fall unconscious, the boy suddenly leaned to one side; his arms held perpendicular to his body at angles. It was unbelievable. I remember jumping up from where I sat, moving away backwards. The boy was twirling, stationed obliquely from the ground, as if held aloft, his face asleep, his eyes half closed, the whites showing underneath. Just like I had earlier felt the Qutub Minar leaning to look at me, the boy had bent at an oblique angle from the ground. This could not be an optical illusion! He was leaning at an almost fifty-degree angle. Perhaps it was the motion that kept him aloft while allowing him to bend, my father suggested.

We huddled together in a taxi that evening and returned home in silence, with our guests clucking in disapproval at the state of superstition in the country. My head buzzed. Life had changed in an unknown way. The metric system was insignificant, in so far as there were larger, unknowable truths in the universe that could not be mastered by working at schoolbooks. The blue-eyed boy had given himself up to the quest of the unknowable, this quest beginning with humility and acceptance, and not by treating the unknowable as something to be vanquished. He had submitted to the unknowable, as part of its quest.

I kept pestering my parents about the Qutub Minar tombs, and after a while they grew irritated. I knew that people were buried, right? So why the fuss about the Qutub Minar graves? It was difficult to explain that these were not just graves, but spaces where there was meaningful presence, greater than life and death itself.

Many years later, watching Ashutosh Gowarikar’s Jodha Akbar, and the song of twirling dervishes staged for an avid Bollywood audience that consumed ‘other’ cultures from the safety of film theatres, I remembered that afternoon spent at the cenotaph of Altamash. I remembered the snow-white flowers, the evening blaze that had lit Altamash’s cenotaph on fire, and the blue-eyed boy with his scornful gaze, who had demonstrated another variety of learning. He had showed me that learning came from giving oneself up to the forces that one wanted to conquer. It was an act, that accorded agency to that, that was desired, and sought to be mastered and achieved. The ‘that’ here, was not a flat object made of ink and paper, but a privilege that only true love accorded to learners, who were in reality its lovers.

Real learning was an act of true love then, and a real learner was none other than a true Deewana!

*

What a lyrical piece of writing!