I worked at an NGO for mental health for five years between 2000 and 2005. These were heavy, but some of the most poignant years of my life, as I made many experiences with persons suffering from intense emotional health difficulties—their indelible stories remaining imprinted on my heart. However, while myself requiring therapeutic support to work in the field, I was lucky enough to be cared for by many loving colleagues, by-now lifelong friends, and mentors. However, I also suffered from terrible burnout and fatigue—so much so, that I left the field, turning towards research instead, and finally, turning away from health studies entirely. This story is an ode to the life experiences from that time—stories about many remarkable persons I met, and was unable to exorcise from my heart—the story about Manju having taken me almost ten years to write.

——

Manju remembered little from that time. That time when the kindly psychiatrist had advised her husband to bring her to the clinic next morning at 7am, on an empty stomach.

“Not even tea?”, she had asked.

“No”, he had smiled, “not even tea”.

They sat in the reception room of an army barrack, its floor made of polished, shining shahabadi tiles. The long room had granite walls, interspersed with deep-seated, narrow windows with trefoil shaped window-panes, set under a vaulted roof supported by painted wooden cross-beams of gleaming white—British architecture, typical of the Deccan. The walls were painted halfway up from the floor, in a dull, blue-grey, shiny plastic paint, followed by a lighter shade that went right up to the gleaming white ceiling. The tube lights and fan hung on long rods supported by the wooden cross beams.

Manju and her husband sat restlessly, squirming in their seats, facing a great desk covered by green flannel, topped with glass. The long barrack room was cordoned off by green curtained partition frames. Since Manju and her husband could not afford to pay, the kindly colonel, an army psychiatrist, had taken them under his wing, asking them to come to the Southern Command hospital for treatment.

“Hope you did not have any tea?”, he asked with a smile, as he bounded in with other uniformed officials close behind him, files clasped in their hands, looking flustered and hurried, their flannel army berets sprinkled with glistening rain drops. The cool morning air and drizzle had gone, replaced by the close, steamy heat and dull blazing sunlight of an oppressive August morning.

Manju knew what she was there for—the forbidden word—electro-shock therapy—ECT. She had seen it in dramatic and frightening movies. The hero would be discovered at the very last minute by his friends, gagged, and strapped to a rusty psychiatric bed, where mad, evil doctors would just be about to torture him with shocks. But no one would rescue her today. In fact, she had not come here to be rescued. She had been told that the ECT would rescue her instead. Rescue her from her problems—from the cutting. As her husband patted her hand, absently she thought, she felt at a great distance from the world—blank, numb, and far away from that room—as if watching herself from above. There was a small gecko in the corner of the room, near one of the windows. She tried to focus her attention on the gecko, imagining how it saw the world, from where it sat. Looking at a girl in a yellow kurta. Did the gecko think she looked anxious? Too worried? Too scared? Perhaps! She rearranged her face. The colonel had not noticed, busily signing papers in front of him. She could see the badge “southern command” gleaming and twinkling on the front of his green beret in the humming light of the table lamp.

As a child of about seven, Manju had the habit of vomiting out everything she was forced to eat. Her mother had been completely exasperated. “Think of something pleasant”, her mother had advised her, while she swallowed one of those sickeningly yellow, transparent, and soft, cod-liver-oil capsules that came in triangular bottles. And while the soft little pulpy capsule slid down her throat like a toad, she often thought of airplanes. She had recently seen a large, life-sized model of one of those at an exhibition in Pragati Maidan, the beloved Delhi of her childhood. She loved airplanes and ran out whenever possible, to watch them in the sky—especially the ones that left behind small, white furry tails. Sometimes when no one was watching, she would salute them, imitating the President at the Republic Day parade. Manju sat there in the green-grey room with gleaming floors, walls, and ceiling, thinking of the soft yellow capsule and the airplane at Pragati Maidan, the gecko on the wall watching her sombrely. They could almost replace one with the other. She would race out of the window into the foliage, and the colonel would give the poor gecko ECTs. She smiled despite herself, feeling rising nausea at the back of her throat. Poor gecko!

¬The depression and instability had always been there, exacerbated by a desire for drama. But at such times, attention was always readily and lovingly provided: parents, grandparents, and many other gentle friends and family members had comforted her. Problems magically solved themselves, and soon, Manju forgot about all the discomfort, tucking in instead, to her favourite goodies. But that word had lingered. It had felt cool and fashionable like dark glasses, the thumbs up fizzy cola drink, dread locks, neon blue, tattoos, piercings, and bass guitar—depressed. I am “depressed” and “mature” she told herself proudly in the mirror.

The real problems began later, after she moved to hostel. She felt unstable at all times. She could not tell friends, and those who only pretended to be friendly, apart. She felt irritated with those who warned her not to confide in others, suspecting them of jealousy, of stealing her thunder. She told her secrets easily and often to a shocked audience. And she liked the ripple of drama this caused. Never mind that they gossiped about her, spreading her secrets behind her back, and laughing at her. Soon, even those who advised her, grew distanced. They began accusing her of constantly complaining. It was confusing and hurtful. Manju tried to impress them—playing the clown, joking around, and laughing—mostly at herself and her own antics. She meant to laugh at herself in proxy, using their words in advance. She even managed to feel mirthful while doing so. They laughed at her antics, sometimes making fun of her in front of her. She briefly felt the ploy had succeeded. They were still her friends.

And then at times, she suddenly tired of it all and withdrew. What would happen, Manju wondered, if she did not emerge from her room at all? She tried it. Nothing happened. No-one noticed. The walls of her room would close in upon her, and after an unbearable eternity, she would finally venture out looking apologetic and sheepish. And yet, no one missed her. Then came the scolding and accusations in class. She had not turned in her assignments on time, she had forgotten there was a test. She was running low on attendance. All those she had been trying to win over now turned back to look at Manju from their seats, their eyes blank, reflecting the teacher’s accusations.

Manju got married. Her husband had hoped for a wife, more matter-of-fact, and practical—certainly not like her. But perhaps, she thought, daily discipline and a routine would help her to achieve stability. Yes, she thought, a daily timetable would help discipline her emotions—like yoga. She would go to office early in the morning, wait in the food que at lunch break, finish her tasks, and her husband would pick her up in the evening. A life that was almost automated.

He was kind to her, “shall we go for a movie?”

“Shall we drink some chilled beer and eat your favourite pizza?”

“Shall we call your friends over?”

The discipline brought in something new—stress. She felt constantly under pressure to finish her tasks, and maintain her routine, and keep to the discipline. She felt her shoulders and neck becoming painfully rigid, because of how tightly she held herself. The doctor said she had mild spondylosis, peering at x-ray scans of her neck. She started getting frequent headaches. She would clench and grind her teeth in sleep. She would constantly worry about the smallest of tasks, the most informal of meetings. Finally, the depression seeped through her much-exalted daily routine. Manju found herself weeping many times a day—in secret. She would weep at her workplace. She would weep, especially when she drank that chilled beer.

But there were good days too. Days when she shopped and cooked and cleaned. All this followed by the plunge, when all the food she bought wasted away, became spoiled, and had to be thrown away. Days when she could not get out of bed. They could not afford it, her husband often said. Yet he did not accuse her. She is young and inexperienced, he thought. Give it time. Maybe she missed her parents. They tried to visit her family as often as possible. Her family, becoming worried, started visiting them more often too, though Manju’s father always felt awkward about living in his son-in-law’s home for too long. But it did not help. They did not know why all this was happening to her. She did not know what was happening to her, and why. It did not feel cool. It felt like a millstone round her neck.

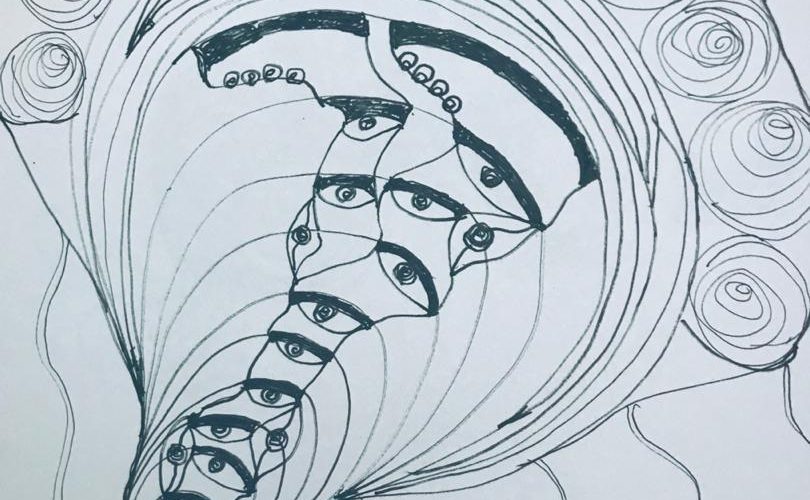

There was an emptiness at all times. She lived in a city of eyes that she felt like hiding from, especially when she was in crowded spaces—local railway stations. She had secretly named Churchgate station the valley of eyes—a sea of unseeing people rushing in opposite directions like unstoppable torrents, many kicking aside a beggar if he came in their way. She felt like that beggar—caught in a torrent that she could not stop, to which she did not belong, to which she was invisible even though she was physically present. She started putting on weight, the waves of depression coming sooner and sooner at her, and almost engulfing her, with every workout session she tried. It was as if she subconsciously wanted to remain fat—simply in order to exist, in order to be visible.

The hole inside her mind gnawed and gnawed on itself. Now with so many holidays taken at her workplace, and so many late arrivals, her superiors started shouting at her. Her colleagues looked at her awkwardly—they grew distant and embarrassed. And gradually, their eyes seemed to join the eyes of her once classroom ‘friends’ and hostel mates—reflecting the accusation of her superiors. She withdrew from them, eating her tiffin alone in one corner.

Manju did not remember who recommended her to the Southern Command colonel-psychiatrist. At first, he tried many, many different pills, and slowly began getting frustrated with the increasing side effects, but no betterment in symptoms. Her husband grew distant, and her parents felt helpless, often apologizing to her husband. Finally, she lost her job, and the world became swallowed by herself—or swallowed her—she was alone in it.

The idea of suicide felt most natural. It slipped into Manju’s mind casually, making her wonder why she had never considered it. She felt the blade of the kitchen knife speculatively with her finger—the one she used for onions. She tried to lay it hard on her arm in a chopping motion, and flinched. No, it was just a scratch. Then she tried to do it again after one or two days, meanwhile always meditating on the gleam of that edge when she washed dishes and cooked. And then, there it was! A big achievement at last—a small cut. A small pale bead of blood appeared on one corner of the cut. Manju felt rising panic as she dabbed at it. But after a minute or two had passed, the blood stopped. A tremendous and overpowering surge of relief flooded Manju, overwhelming her. It was such a small thing, and it was over. She had managed to cut herself. She felt a deep knot inside her, loosening up. This relief felt like a shot in the arm that gradually spread its fierce glow all over her body. It was physical, almost bringing the reeling world, the kitchen around her, into new focus and fresh colour. She smelled the pulses bubbling on the stove intensely, inhaling its heavy aroma, feeling reborn. She was back in control over her mind and body. This control was bigger than what she had ever experienced.

Cutting brought Manju tranquillity. The anxiety about the inexorable plunge, when she could hardly raise her head from a tear-soaked pillow, precariously cannoning into fits of rage that accompanied it, lessened. The chilled beer flowed more freely. All the while, Manju kept secretly cutting herself every time she felt uncomfortable and anxious, to regain control over the sudden instability. She started doing it everywhere she went—excusing herself during her office meetings, in the middle of family dinners at restaurants, while talking to someone on the phone. Every time she felt too crowded by an overwhelming instability, she cut herself. It soothed her—it brought her back into control. In fact, the cutting was an almost spiritual experience. And it was such a bore that she had to keep it secret. People did all sorts of extreme sports openly. That was torturing the body too, wasn’t it? Boxing! For God’s sake! No one ever questioned that! So why did her teeny tiny cut have to be such a sordid, big secret? It had a wonderful transaction-like value to it, that brought closure—averting the uncontrollable.

“You are improving at last”, the colonel-doctor said. “Yes, she has improved”, her husband said, the flooding relief palpable in his voice. She looked down at her hands in her lap, pulling the sleeves lower over her forearms and wrists.

But of course, she was discovered, and red handed, at that!

“What are you doing?”, her husband had conversationally asked, walking into the bathroom, grabbing at his toothbrush. He looked on blankly, as a drop of blood fell into the wash basin. “Did you accidentally cut yourself?”, he asked. Another drop fell into the wash basin. Then he saw the small blade in her hand. “What on earth are you doing?”, he asked, his voice almost a whisper. He shook her shoulder. “What were you doing?”, louder this time. He pulled up her sleeve, and she heard him harshly gasp and swear under his breath. “Since when?”. Without waiting for her to answer, he left the bathroom. Following him into the bedroom, she found him sitting on the edge of the bed, his forehead cupped in one hand that still held the toothbrush, the phone receiver clasped to his other ear. He was talking to someone.

“Come tomorrow morning at 7am on an empty stomach”, the kindly colonel-psychiatrist was telling him, asking him to pass her the phone, as he explained that she must remove all her jewellery at home, before coming to the hospital.

“Not even tea?”, she had asked.

“No”, she could hear the smile in his voice, “not even tea”.

“It was too good to last, wasn’t it?”, her husband said. “You could have died, you know!” And when she said, “oh no!” sounding complete assured, he looked at her dumbly, toothbrush still in hand. That day she met the gaze of a stranger, as he too must have. It was like the gecko on the wall. She saw it, but what did it see, looking dumbly and blankly at her? Was it accusing her—like the eyes of her classmates and colleagues in the classroom and at office? What was it the gecko really saw?

There was first a stretcher, from which she had to climb on a higher, narrower operation table. The doctors and anaesthetists were dressed in green overalls and caps, and the bed sheet on the narrow operation table also was the same green. The anaesthetist was jocular. “Where did you study?”, he asked her. “At Stephens in Delhi.” His fingers that were tapping at the crook of her elbow stopped, as she saw him grin behind his mask. “Really? And I am from Hindu college, across the road from you. We won against you guys in my last Mukh-Mem, though.” She laughed. The traditional Mukherjee Memorial debate between Stephens and Hindu! He could be talking about another world, another planet! The heat at the crook of her elbow was the last thing she remembered. And all she recalled of those ECTs were whining sounds coming closer and drawing away again—perhaps every electrode that touched her temple, whined.

Manju was not alone. Another girl was also being given ECTs in the southern command hospital on the same days as Manju—they grouped their ECT patients it seemed. Though Manju had large memory gaps from the time, she remembered the actual days of the ECT more clearly, than the time in between and around them. Waking up with a pounding headache in the recovery room, the cot covered with the green sheet, Manju saw a large drop of dried blood on it that had dripped from the crook of her arm, now covered by a bloodstained cotton pad and plaster. The other girl lay on the cot across from her, and she was awake. They looked at each other. The girl’s mother was sitting at the edge of her cot, across from Manju’s mother and talking in low tones. The other girl’s mother was talking fast, and nineteen to the dozen, telling Manju’s mother that her daughter was perfectly normal, but needed ECTs only because of examination tension. They all looked at the other girl, who shut her eyes.

The next time, waking up in the cot across from the other girl again, Manju asked, “are you really so afraid of exams?” The girl said nothing. Just nodded, clutching the green sheet to her neck, shutting her eyes. They began speaking a bit more after that, always waking up next to each other after ECT. Manju gathered that this was the second time the other girl was being given ECTs. Once when the mothers, having become friendly went outside to the canteen for tea, the other girl dropped a bombshell.

Slowly slipping off her cot, and self-consciously smoothing her hair and dress, bending down to look for her slippers beneath the cot, she conversationally said, “you know, I was abducted by aliens.” Manju did not know how to respond to the other girl, and after a long moment of silence asked, “how do you know it was aliens?”

“Well, they are like plain clothes policemen. You cannot tell them apart from real people. And yet, they are there everywhere among us, keeping a watch over us.”

“And what happens then?”

“Well, they catch you, and then do experiments on you, and your whole mind changes. You cannot remember anything you have studied for your exams. And they begin controlling you like a robot. Then you slowly turn inert, and then ultimately die. Therefore, you cannot have children, or marry.”

“Why can you not marry and have children?”

“Because aliens have AIDS. AIDS is a sign that you are either an alien or are being slowly turned into one through HIV infection. It is exactly like in that movie, Matrix. Therefore, you must always avoid people who have HIV and AIDS. And this is very difficult, because they are all around you. So, you can never trust anyone enough to marry them. They may show you a false negative report, but that does not mean they don’t have HIV or AIDS. Then they slowly turn you over to the aliens.”

Manju asked the other girl, “do you have HIV or AIDS?”.

“No, not yet. I am resisting them, since they are using my mother to gain access to me”.

“Do you have HIV or AIDS?”, the other girl asked Manju.

“I don’t know”.

“Well, find out then, whether they are trying to recruit you! Maybe the mental problem comes because of that. They want to abduct you and so they weaken you at first. Your husband is probably in on the plan”.

Avoiding the comment, Manju asked, “doesn’t it make you sad, that you can never have children?”

“No!”, the other gave a secretive, triumphant smile. “Who wants to turn into a vegetable, and die?”

On the last day of the ECT session, as they all said goodbye, the voluble mother of the other girl half-wailed, and half-scolded her in front of everyone, “Oh, why don’t you lead a normal life like this other didi here?”, she pointed at Manju. “Why don’t you marry a nice, understanding husband like she has? What is wrong with you?” The other girl answered coldly, “so what? She is still taking ECTs isn’t she?”, before turning away. “Please excuse my girl”, the voluble aunty apologized. “She has got it into her head that everyone around her has AIDS or HIV. Her precondition for marriage is that every prospective groom must submit a negative AIDS test certificate to her every week, even after marriage. She saw some English movie about it. She feels that these ECTs are trying to convince her to marry. Who will marry my daughter in such a condition?!” Her eyes filled with tears. “You are lucky”, she said to Manju, patting her shoulder, “all the best beta!”

——

I have deliberately written Manju’s story from a self-reflexive perspective. For instance, many readers would automatically empathize with Manju’s husband, Manju’s parents, the kindly colonel-psychiatrist, and the other girl’s mother. My point here is not to demonstrate the violence implicit in the mental health diagnostic system by vilifying families, relationships, or the overloaded medical fraternity in India. My point is instead to demonstrate, how difficult it is to empathize with persons who are suffering from emotional difficulties—be it depression, anger, paranoia, or extreme anxiety about social and sexual relationships. It takes effort to read this story against its grain, from Manju’s or the other girl’s perspective, and primarily have empathy for them, instead of “othering” them as lunatics. And yes, all this despite their medical diagnosis. This is what we really need to learn as not just mental health professionals, but as human beings, social beings, and family members, especially in hard times like lockdowns brought on by epidemics, climatic, or political crisis. As we depend on each other ever increasingly for social contact and comfort, we need to unlearn the “normal”; stop automatically conflating the normal with safety and goodness, because those we label “abnormal” are also products of this same normality, that prescribes the non-emotional as healthy. This is harmful. I spent my small career in the mental health sector in India learning this important lesson: that being normal was not necessarily being good or being more human. There was a lot of humanity to Manju and the other girl. Their emotions did have an internal logic. It takes reading her story against the grain of “normalcy” to understand how she is included within the same society that excluded her—she was not an outsider; she was not alone. And yet she was made to feel like one.

Millions of young people in India, mostly women, undergo psychiatric “discipline” within the mental health diagnostic system, because these systems do not accept the conundrums of individuals, seeking their own place within structured and formal groups. These persons, seeking friendship and love in unstructured, unconditional ways that recognize and appreciate them as individuals first are often shattered by control groups that gate-keep conformity. This is what leads many sensitive and vulnerable individuals to feel disembodied—like geckos on a wall.

This is where the crux lies: as Manju constantly apologized for being herself, she struggled within a system made of groups, that was not configured to her individual needs of unconditional affection. The system, instead, isolated and excluded her further, leading her to becoming the case of the other girl over time—someone who had lost trust entirely. Yes, Manju and the other girl, broken-up in the story as two protagonists, are one and the same case. While a lot is written within scholarship on caste, religion, or gender as heuristic forms of social discrimination and exploitation, very little is written on emotional and mental health as social experiences. Those who write about emotional health, move on to advocacy and policy, which is OK too. It is important, however, to “stay” and engage with the experience of emotions, however-much suffering they bring, with dignity, without rushing to “solve” it and see it as a “problem”.

While various sting operations of mental hospitals and community healing centres shame governments and communities by raising awareness about family abandonment and systemic abuse, which they should do, very little awareness is raised about a reified sense of emergent society and hegemonic group-building within the helping community itself—an activist/ values/ ethics conformity that creates outcasts through its own processes of becoming. Emotional laziness and general restlessness with the labour implicit in the sector: “staying” with the experience of suffering, instead of rushing towards reforming it, does more harm than good, recreating another version of the same system that was originally critiqued. This simply inaugurates multiple generations of and within the same system that shrinks away from staying with the silence of narrative experiences that undo conformity!

It’s easy to feel angry about someone’s suffering, rather than dignify the suffering by staying with it, engaging with it, and having enough courage to desist from changing or resolving it, against the suffering person’s own will. While many activists would consider this unethical, dignifying and staying with suffering that is itself a form of protest, is the basic labour of the mental health/ emotional health sector.

*

Add comment