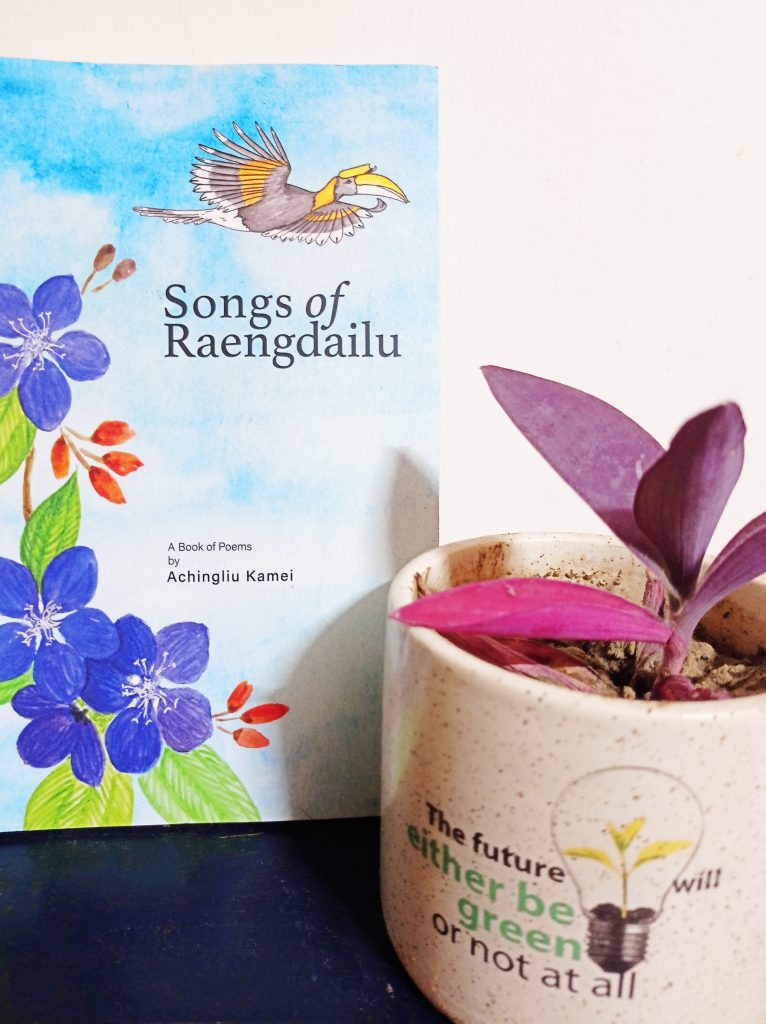

A few days back, during a talk on ‘Why Literature’ in Kolkata, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak mentioned William Wordsworth as a ‘consumer of nature’. I was reading Achingliu Kamei’s Songs of Raengdailu during that period. Somehow the phrase stuck with me and added a new dimension to my reading of Kamei’s poems. If Wordsworth is the consumer of nature, drawing his creative inspiration and rejuvenating himself through its benevolence, poets like Mamang Dai, Esther Siyem, or Esterine Kire live ‘nature’. Their poems are born out of their everyday, becoming a part of the greater ecology, and not an outsider reaping benefits from it. These poems become an extension of the lived realities that is more organic and closely associated with the topography, flora, and fauna of the region. Achingliu Kamei’s poetry is carrying forward that legacy of writing. Her poems are born out of her ‘way of life’, and her lived experiences. There is an umbilical cord connecting the soul of the poet to the core of nature.

I never farmed, but it’s as if I had

My soul is like a farmer, it understands the wind

It can feel the rain in the air, it can read the clouds

It can feel and live the seasons

It can hear Nature (Song of Soul, 63)

There is an apparent simplicity of diction and style. But it is not the simplicity that lulls one into easy reading. It makes the readers engage with the poems and think. Her liberal use of indigenous words forces the readers to step out of their comfort zone and engage with the poet’s world. The very first poem transports us to the fields in the North East where women, in spite of their back-breaking work, have to go hungry most of the time, as menfolk eat major portions of the packed lunch. It’s the local wild plant puangbiu bang that sustains them in such times,

Never bringing you home to domesticate

Like the other exotic flowers, yet I know you are the loveliest

Giving yourself to sustain another unacknowledged flower

From extinction, from hunger, from overwork,

You took a chance on her, and her descendants – for generations. (Puangbiu Puang, 24)

In the note to this poem, the poet explains how the plant, puangbiu puang provides respite to the hungry and tired women returning from the fields. The women chew the stalk of this plant to stall their extreme hunger. The wildflower is not just a symbol, but an apt companion for these women, who are equally uncared for, yet has the tenacity of a survivor.

This slim volume of 52 poems is divided into two parts. The first part consists of poems that talk about her place, the second part is about women. The first part has been aptly referred to as ‘poetry of geography’ by the eminent poet Easterine Kire in her foreword to the book Songs of Raengdailu. Kamei brings out the pristine beauty of her native place. The contours of her landscape and that of her mindscape complement each other. The mountains, rivers and plants present in her poems are not mere metaphors but a part of her life. These poems also contain a deep critique of the modern lifestyle, expressing concern regarding the all-consuming greed of humans, and their anthropogenic activities. But this categorization of the two sections is not sacrosanct. It is broadly based on the general contents of the poems. Quite often the identities of nature and women merge overlap and exchange places, making it difficult to categorize the poems into any one of the sections. Her voice is that of an ecofeminist who is appalled by the outcomes of the corporate-induced mechanization of this progressive society. In the prose-poem ‘Tiger Spirit Man’ Kamei says, “It seems the tree of life is fast denuding and under apocalyptic attack from its ungrateful and war mongering human offshoots” (39). The nature that she talks of in her poems is an extension of her self. Aware of the true position of humans within the larger ecology, her poems protest against disruptive human activities. In ‘Banshu, Fireflies’, she is critical of the artificial lights of human settlements that are driving the fireflies, one of the most beautiful creations of nature, away from their natural habitats. In an empathic voice, quite rare in today’s world, the poet says,

Fireflies of my childhood days

Life merging under starlight

Her blink in tandem with the blinking

Of the distant stars

Sounds of laughter and wonder

I long to leave it to my children

Turn off the lights at night during firefly season

Ensure you have a beautiful display for years to come. (82)

The poet, the ecologist, and the advocate, all meld into the personality of the poet through these lines. It is a direct appeal to humans to be more sensitive towards nature and not destroy the habitats of other living creatures. But it is not all just advocacies. The poet also writes of love and loss. The poem ‘Carve it out and bury in under the flame tree’ is a poignant evocation of the yearning for the dead partner, ‘one talon of pain still clawed at his heart’. In the ‘Lonely winter evenings’, the poet mourns her mother, revisiting tender memories of their togetherness. The tone is soft and lyrical, a shade of melancholy running through the verses.

Poems in the second part of the anthology narrativize the concerns of women. She speaks in an unrestricted voice about the violence, oppression, and exploitation that women have to face. The poet is more of an activist here, raising her voice to protest the injustices of a woman’s life. The poems touch a raw chord with their stark honesty.

I am just a woman

Fire burning in my eyes

Reflection from the hearth

I am just a woman…

I am just a woman

My womb holds humanity

My only authority. (129)

The simplicity of the words hits right at the heart. There is an economy in her words and expression which rejects superfluity of all sorts – both in content as well as form. She is the story teller, narrating untold stories, and creating a repertoire of lost and forgotten voices.

I remember, I remember

The skeleton stories of the victims

On less known pages of forgotten books

Marked ‘Lest we forget’; ‘Bearing Witness’. (I Write for You, 125)

The poet is the chronicler, keeping a record so that the world does not forget. The conflicts, the army, the hardships of the people living in the hills of the North East, and the griefs of a mother or suppression of women – all get recorded in her poems. Yet, she also sings of hope and of overcoming hatred and fear,

We release you, fear, and hatred, because you hold,

These narratives from the time we saw and heard. (Songs of Raengdailu, 127)

Hornbills symbolize the spirit of the Naga community, reaffirming the positivity of life. Raengdailu is the female hornbill. In the title poem, Song of Raengdailu, the poet lets go of the negative spirits of hatred and fear and frees her people from their restrictive, and disparaging clutches. The anthology is also justly titled Songs of Raendailu. In an explanation regarding the title of the anthology, as mentioned in the Foreword, the poet says, “I have chosen to use Songs of Raengdailu as the title to assert women’s position in the social standing as an equally important counterpart to men, to give exigencies to women’s voice, and as a way of survival” (7). In this anthology, Kamei speaks for the women, of the crimes that society has done towards them, and their spirit of resilience in spite of all hardships.

Achingliu Kamei’s poems remind us again and again of human existence as a part of the larger ecological design. They illustrate the concept of deep ecology, presenting an alternative, organic lifestyle that grows with nature, not in spite of it. She also is an activist who composes verses of freedom, justice, and equality of gender. She is a recorder of stories. Her stories, that originate in the hilly regions of Nagaland, transcend their ‘locality’ through the global nature of her concerns. The world, that is becoming sharply polarised and binary, the world that is moving towards self-extinction through its predatory practices against nature needs more voices like that of Achingliu Kamei’s.

*

Add comment