heads tumble off, from time to time/ some old, some young/ the bus conductor calls out/

‘keep moving, backwards’

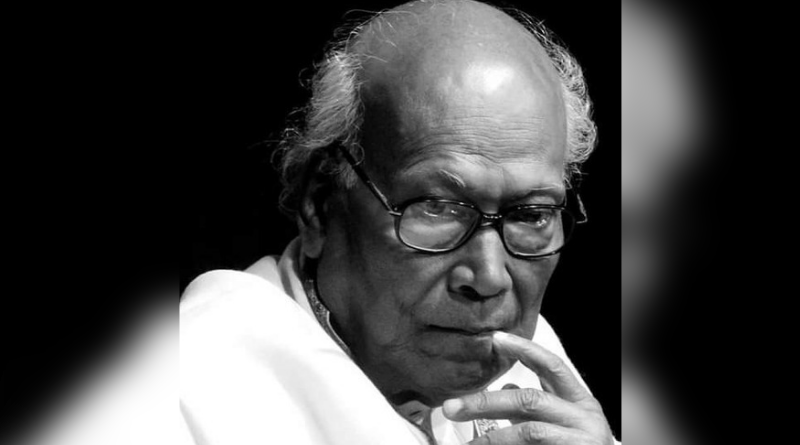

These lines from the Bengali poem Jam, by Shankha Ghosh, was a sketch of the political landscape of West Bengal and the majority of the country in the 1970s, paused at the crossroads of the old and the new. While rooted in time and place, the lines also have a universal appeal which would have resonated equally well in an underground bar in Franco’s Madrid or a protest march in Trump’s New York. This universality, combined with a profound faith in humanism, was the true power of Ghosh’s poems. Along with contemporaries Sunil Gangopadhyay, Utpal Kumar Basu, Shakti Chattopadhyay and Benoy Majumdar, he had formed what came to be known as the Pancha Pandab (Five Pandavs) of Bengali poetry in the post-Jibananda Das era.

Born Chittopriyo Ghosh in Chandpur (now part of Bangladesh) in 1932, he spent his adolescent years in Pabna, where he completed his matriculation in 1947. After partition divided the country, his family had to migrate to West Bengal. The culturally fertile North Calcutta of the 1950s, where he completed his BA from Presidency College and Master’s Degree from Calcutta University, shaped his political ideology and forged his voice as a poet.

His first poem, Dinguli Raatguli, appeared in the iconic literary magazine, Krittibas, in 1953 while he was still a student at Calcutta University. Three year later his first collection of poems, bearing the same title, was published to critical acclaim. In the decades that followed, he produced many seminal works like Babarer Prarthana (1976), Tumi to Temon Gouri Nou (1978), Prohor Jora Trital (1982), Jal-I Pashan Hoey Aache (2004) – all resonating with lyrical sensibility, political undertones and a compassion for the human condition. Like his contemporary Ritwik Ghatak, Ghosh remained deeply troubled by the partition of the country, and the angst of rootlessness – coupled with images of his childhood days in Bangladesh – resurfaced in his poems again and again. The themes caught on with readers across the border, making him a household name in both West Bengal and Bangladesh.

One of the most prominent authorities on Rabindranath Tagore, Ghosh taught at many institutions like City College, Delhi University, the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies at Shimla, Visva-Bharati University and the International Writing Program at Iowa, before retiring from Jadavpur University in 1992. He was awarded the Sahitya Akademi twice – in 1977 for Babarer Prarthana and in 1999 for the translation of Girish Karnad’s Kannada play Taledanda. He was also honoured with the Padma Bhushan by the Government of India in 2011 and the Jnanpith Award in 2016.

While his poems often carried political and social themes, he neither aligned himself with any political party nor shied away from raising his voice against those in power – irrespective of their political affiliation. He opposed the Left Front government in West Bengal after the police firing of Nandigram in 2007; he opposed the Trinamool Congress for perpetrating violence in the 2018 Panchayat polls. Mati, his protest poem against BJP’s NRC and CAA, won him critical acclaim from the public and the intelligentsia.

Ghosh died on 21 April 2021, at the age of 89, leaving behind a complex legacy of work which captured the tumultuous, post-independence decades of India’s history – the pain of partition and migration, naxalite movement and the emergency years, economic liberalisation and the country’s descent into politics of hate – like a montage of carefully curated images. This legacy, a portal between the past and the future, will continue to remain urgent and topical to generations in the years to come.

—–

Add comment