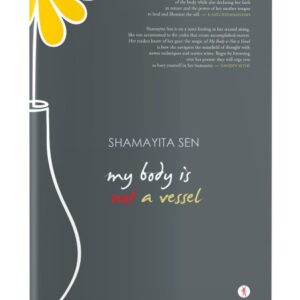

May you be a mother of a hundred sons – one of the oft used, most glorified blessing, even now continued in various modified forms, is a reminder of how culturally and socially a woman’s body is treated as nothing but a vessel—a vessel to give birth to sons, and on second thoughts, to daughters. The identification of female sexuality with child bearing and looking at her body as an object of sexual pleasure are the banes that feminist activists have been resisting for years. Both these identifications become tools in the hands of patriarchy to perpetuate the position of women as the ‘second sex’. The anthology, ‘my body is not a vessel’ by Shamayita Sen, published by Hawakal Publishers, is an attempt to resist these straitjacket brandings of the society. The intention of the anthology is defined right from its cover where the word ‘not’ from the book title is written in red, making it stand out from the rest. The title itself is a protest against the prejudices of a patriarchal set up. From the very beginning the poet is making a statement, taking a stand against the idea of woman as just a body.

The book is divided into three sections—‘My body is a Metaphor’ with 28 poems, ‘In Mourning’ consisting of 27 poems, and ‘Homecoming’ with 29 poems. The poems included in this anthology in terms of both form and content are diverse, not allowing the readers any dull moment.

As the title of the first section suggests, for the poet, the body is not just any metaphor, but a symbol of a thriving, conscious presence. In the tradition of l’ecriture feminine she uses the body to script her experiences. It’s an act of reclaiming—the female body which is also a site of exploitation and coercion, is used as a powerful symbol of identity. In these poems, there is an unhesitant expression of female sexuality and female experiences that is not very common. She talks about the pains that the woman has to go through and blood becomes another significant metaphor:

“Five days post release, my sister sits on her bed, bleeding, snuggling pain in her womb, Her womb, that is to bear futuristic male children, needed cleansing of fibroids.” (15)

Or,

I run down the beach, ecstatic.

The bulging breasted sea

I made love to all afternoon has

bloodied my bed with her adolescence. (24)

For Shamayita Sen, poetry is a way of life, it is gleaned from daily experiences—both soothing and unsettling. Pregnancies, child birth, menstrual issues, domestic violence, sexual abuses—all these and more become the part of her poetry. She can write as easily on ‘How to Insert a Cup’(18) as she can about the domestic help’s attempt to hide the bruises received from her husband (Winter in Kolkata (25).

In the poem, ‘The Pink Tax’, the feminist in her is piqued at the unjustness imposed by fashion industry and perpetuated by women themselves –

‘Pockets in women’s/ clothing are a delicacy, an expensive endeavour,/ chargeable under Pink Tax’ (30).

The poet is ironic, sarcastic, scathing, and uninhibited in pointing out the deprivations and exploitations that women face in the hands of patriarchy at all levels, beginning right from her birth –

My uncle wailed all night

grieving the birth of his girl-child.

So they tried for another.

His firstborn is now

a medical practitioner. (31)

The mood changes in the second section of the anthology, ‘In Mourning’. The tone is sombre. Loss and grief runs through all 27 poems but then grief for the poet is not just a time for lonely mourning. There is an inherent socialism in her poetry and in her beliefs which leads her to constantly map the exploitations and hypocrisies of the society, be it at home, or at the cemetery. The poet, in spite of a deep personal loss, can say – I stood wondering, the sweet marinade/ of curd-rice offered to Baba would/ serve its purpose better if provided/ to the purohit or maid lurking/ in shadows.” (47).

Grief and mourning is personal, intimate, and the body is its repository – My body is an aquarium where I bury/ experiences fossilised to be later used/ as metaphors” (56). Even the city becomes an extended metaphor for her sorrows. Smog of Delhi is an ode to her loneliness and deprivations – “This evening becomes a gleaming light, a reflection/ farthest from its source, the kind that is stuck/ between what is and what could have been” (68).

Grief and mourning is personal, intimate, and the body is its repository – My body is an aquarium where I bury/ experiences fossilised to be later used/ as metaphors” (56). Even the city becomes an extended metaphor for her sorrows. Smog of Delhi is an ode to her loneliness and deprivations – “This evening becomes a gleaming light, a reflection/ farthest from its source, the kind that is stuck/ between what is and what could have been” (68).

Home is an important metaphor in poetry at all times, and is generally associated with the idea of return, of longing and nostalgia. In the third section, ‘Homecoming’, the poet talks about cities, food, seasons and memories. She also talks about the touches that make her feel at home –

“We sit close—our thighs brush against each other, you doodle patterns on my knees…and momentarily I forget we are out amid stares.” (93)

Her ‘homecomings’ are marked by absence too—of people and experiences. She begins the section with a short poem ‘Absence’.

Your absence

Smears my bones

With memories of belonging.

I’m rendered naked

Like a frame

Bereft of bricks. (79)

In the postmodern world of shifting bases, where moving across cities is just another form of living, the poet finds home in several places. So Kolkata, Delhi, Bangalore, all find a home in the poet’s world. In the poem ‘Shifting Cities’ the poet shows how a change of city is not just another change of address but multiple negotiations, both practical as well as emotional.

And I realise, I’ve mastered the art of letting go:

I place withered flowers, dried leaves, and

Ad hoc friendships on my tender palm,

Only to flicker them off with stern fingers. (102)

Shamayita Sen’s poems in my body is not a vessel are often hard hitting. Though apparently simple in their tone and form, they are at times sarcastic, ironic or just direct – pointing out the exploitations of patriarchy. But the poet is also capable of expressing tenderness, as seen in some of the poems in the latter two sections. The body remains an important metaphor that binds all the three sections together. She is rightfully unabashed in her delineation of female experiences and celebrates her femaleness through her verses. Pauses and gaps are her tools to make the creative language a site of power. In the times of dominant heteronormative narratives where female sexuality and alternative sexualities are either under threat or relegated to the margins, Shamayita Sen’s bold voice rings loud like a beacon of hope. These short, simple poems are incisive, thought provoking as well as a pleasure to read. This anthology is a must read for anyone interested in the feminist voices in particular and for poetry lovers in general. .

*

Add comment