After what seemed an unending hiatus, the Kolkata Book Fair finally happened this year. The being out in the open, of being with books, of browsing through them, of meeting up friends and acquaintances, of book launches, poetry readings, of discussions, things finally seemed to be working their way back. There is always an air of nostalgia about the Kolkata Book Fair for me. My reading this month was a novel that I picked up at the Book Fair.

After what seemed an unending hiatus, the Kolkata Book Fair finally happened this year. The being out in the open, of being with books, of browsing through them, of meeting up friends and acquaintances, of book launches, poetry readings, of discussions, things finally seemed to be working their way back. There is always an air of nostalgia about the Kolkata Book Fair for me. My reading this month was a novel that I picked up at the Book Fair.

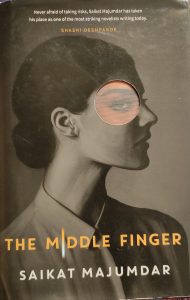

Saikat Majumdar’s The Middle Finger takes one into the world of poetry, of teaching, and of human relationships. As the novel moves through classrooms in universities in the US and India it brings in notions of class and gender. Megha, the protagonist of the novel, is a poet who writes about the world around her, of her experiences and of relationships as she sees them unravel. She gives up writing her dissertation at Princeton –

She had written almost 30,000 words of the dissertation. She was trying to draw out hidden stories of magic, myth and opium in the literature of the long 18th century. Stories that fought the period’s new arrogance of science and techonology. . . . Poetry called her in a different language.

Though Megha enjoyed writing poetry she did not like the sound of her poems as they were recited and performed by others. When she heard them being read, she felt as if “The words crawled on . . . [her] skin like large hairy ants . . .”. Her lines “sounded alien” to her as she heard them. “Why did they bleed so viciously when other people spoke them aloud?” Was it because she claims an ownership to them that she feels thus, one wonders.

Megha moves to Delhi from the US to teach. It is in Delhi that she meets Poonam, a Christian girl from Jharkhand who is awe of Megha and her poetry and looks up to her. It is class that has prevented Poonam from completing her studies and in Megha she thinks she finds her mentor. When Poonam wants to learn from Megha, she refuses saying that she is not good at teaching the “kind of teaching” that Poonam needs. “Poonam spoke English, broken English, sentences broken into pieces, sometimes glued together, sometimes unglued, scattered” and as she listened to Poonam, Megha’s “hear sank”. Poonam is content taking books from Mgha – “I love reading poems and stories and will you let me take them . . . didi”.

Poonam is the Ekalavya to Megha’s Drona and it is from this story from the Mahabharata that the title of Majumdar’s novel traces its origins to. I must say that the title had left me wondering the first time I saw the book cover. As I read the novel I must say that it is a title that wonderfully captures the essence of the narrative. The novel also brings in the reference of Socrates and Agathon, another teacher – student pair from Plato’s Symposium that the epilogue to the novel refers to. These two stories also bring in questions of privilege, of belonging which are important thematic aspects of the novel. In the US Megha is aware of the fact that she is the other, in Delhi, her position of privilege becomes even more clear. She gets angry with Poonam for leaving stains on the carpet that her guests might notice. The desire between Megha and Poonam is slowly revealed in a very nuanced way in the novel. The first time they meet, this is what the novel lays out for us – “Poonam stepped closer to her. Megha could smell her hair, its rusty oiliness.”

The Middle Finger also brings in the idea of home in a world that is fragmented, in a state of flux. “Megha walked inside with a tired smile. Sometimes she felt horrified to imagine what her house and her life in Delhi would look like without Mr. Ajmal, Reynld, and Poonam.” The homes Megha inhabits as she grows up, attends university and then begins to work, each have a different meaning for her as she negotiates her identity and her sense of belonging.

Poetry is an important aspect of The Middle Finger. The novel speaks of ways in which poetry can reach out to all, of the ways in which one learns to read poetry and make sense of it all in a world that is harsh and insensitive, where privilege and class make things difficult and complicated, of the way it draws in and holds so many levels of meaning for many as they go about negotiating life. Majumdar’s language itself in the novel is poetic, capturing the essence of fleeting moments, of relationships, of life as it lingers and moves ahead.

*

Add comment