For Mama- November 27th 1949-August 11th 2022

In Madras, sometime in the mid-eighties, I’d accompany my mother to the post office. After addressing her envelopes containing submissions to prestigious magazines in America, she’d hand them over to me to drop into the postbox. In my twisted reasoning, I felt her aspirations were hampering mine- like most children, there was in me, a smidgen of potential for art.

And I was encouraged; this firangi aunt whose portrait I scribbled away into the night added to that illusion of precocity. I was too young to know I really had zero talent at drawing, or at least no real passion for it and thus chose to suppress my mom’s efforts at recognition; I’d peel away the stamps on her envelopes before posting her poems. I remember having done this on a few occasions; but for her, those envelopes were stamped, they made it to an editor’s desk in Chicago, or London, and prolonged her hopes, till it struck her they weren’t accepted. Regardless of whether the poems were good enough to be selected, through my mischief, I greatly reduced the chances.

At that time, my mother, who went by the nom de plume of Padma Sundari, was one of the few Indian women poets writing in English. I still remember playing with her typewriter ribbons, smearing the ink on walls. It wasn’t until years later, when I’d long forgotten I wanted to be a painter, and when I published a few poems of my own, developing a sincere interest in the art form, that my focus turned to her published work-but why wasn’t I ever conscious of her as a poet before that? It might’ve been because there was no Facebook then; the only platforms were the occasional poetry gatherings, and you usually did not get to read unless you were in the fold-something she’s always been averse to. The reason could be beause a senior poet tried exploiting her position as a bank officer at IDBI to fund his cultural event. Or maybe, her aversion can be traced to a poetry reading she tried organising at her flat in Colaba in the late 70s. Only two out of the seven or so poets who were invited actually turned up; Santan Rodrigues and another writer, whose name she cannot recall- by her own admission, “they just bitched about other poets and left-there was no reading at all.”

But the more plausible reason behind why I wasn’t conscious of her as a poet was that she’d long stopped writing poems. And excelled in her “real” career.

It’s now been more than a decade since she retired from her bank job, and a decade more since she resigned as a writer; but I still carry her visiting card in my wallet. It says, “Padma Rajendran, General Manager”. But there’s no visiting card of her as a poet, with her nom de plume. When acquaintances remember her, they do it because only being a high ranking officer conferred upon her a status. To confess, predicting her obituary, I bet the few who might recognise her otherwise wouldn’t know who died if I wrote her down as a poet. I’m not even sure if she’d recognise herself as a poet in her obituary.

During our early conversations about writing, some literary names would turn up. This was when she’d attend to my doggerels for hours, paying them far more attention than they deserved.

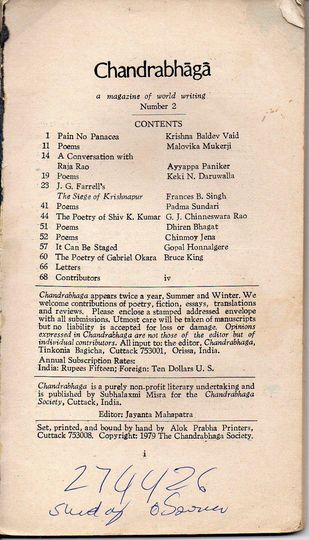

The sessions were always about me, isn’t this line so powerful? Does that usage make sense? I’d shrug off the mention of Chandrabhaga, or her tribute to Smita Patil, or when she’d talk about those afternoons at the American Library in Bombay, discovering poets who still ignite her when they’re discussed.

For a long time, I have wished she weren’t as kind to my endeavors. I bristle now that she nudged me to send a pitiable manuscript to The New Yorker, about 20 poems I wrote when I was 19 and hardly a year into my writing. During my India trips, I cringed when I saw those foolscap notebooks with butterfly covers, as I learned that all my maudlin, amateurish attempts had become five spiral bound ignominies. I understood her need to archive “poems” that were crucial to my growth but there was nowhere to bury my head when I read my utterly nonsensical attempts, including one called “London Buses Wear Bras”. But it now occurs to me that maybe she was aware of the dangers of interfering too much with the creative process; of bringing a critical, objective assessment to my work. But yes, she never held back when it came to introducing me to other poets, and in sharing her criticisms of their poems. If I’m able to spot literary pretensions now, it’s because she drew a clear, and perhaps overly harsh distinction between who’s being clever and who’s the real deal.

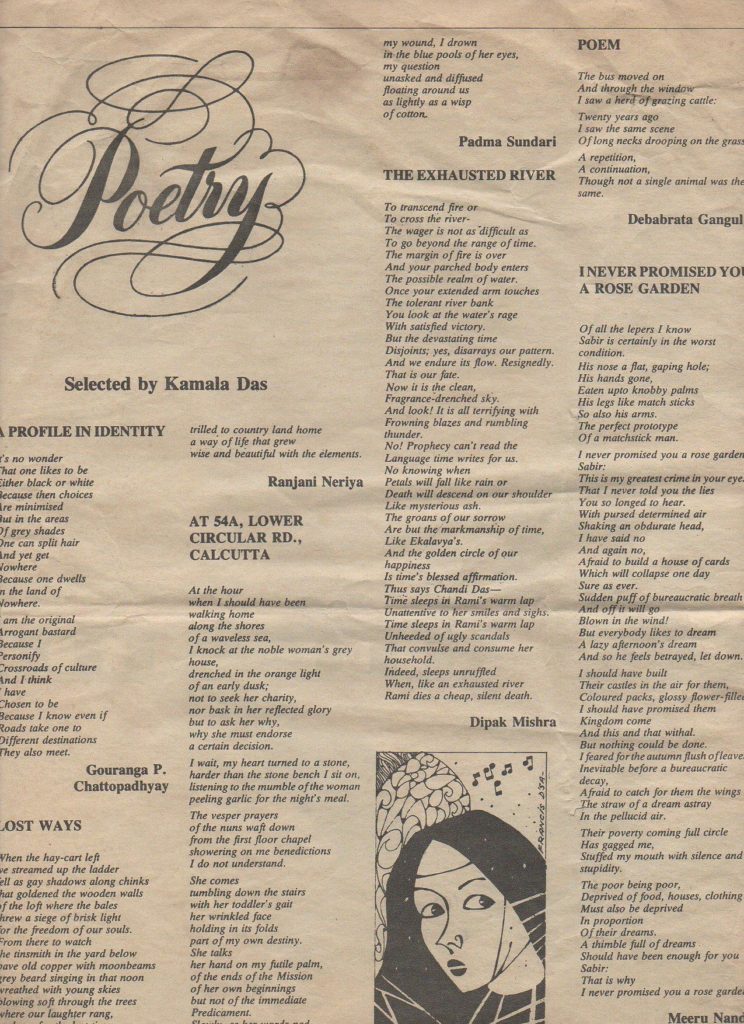

And if yesterday, I shared a poem called “Digging”, and received so many likes for it, I surely failed to acknowledge that my mother introduced me to Seamus Heaney. And T.S.Eliot. And Kamala Das. Keki Daruwalla, Arun Kolatkar, Anne Sexton, this “interstices” poem in the Times Literary Supplement, that brilliant pornography in POETRY, to Carl Sandburg, Pablo Neruda and most of all, Jayanta.

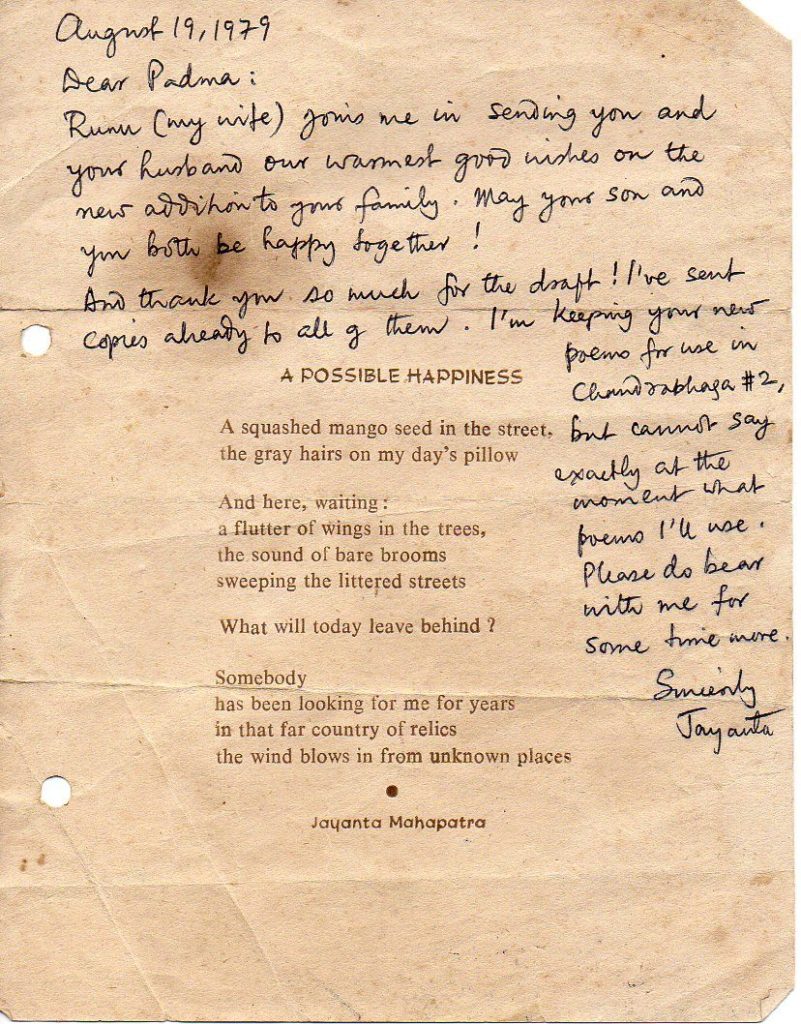

Even more than Eliot, Jayanta Mahapatra is the poet she’s imbibed-“a silence that tells us the world is not our’s” is a quote I often hear from her lips. Although they exchanged letters for a few years, it wasn’t until much later that she got to meet him; sometime this millennium, when she happened to be in Cuttack and obtained his number from the operator. The details of the visit that followed are vague, but I’ll never forget her recollection of that brief telephonic conversation, how the octogenarian traced her in a second, as a poet he was proud to have published in x and y issues of Chandrabhaga, and only twenty-odd years ago.

When today, I see some of the biggest deals in the Indian canon, I’m dizzy my mother was once featured alongside them. I display her correspondences with Jayanta Mahapatra in my album with as much pride as she’s nailed the laminated printout of my first publication in the hall. And almost always, when I share her work with others, I’m asked why she stopped writing. I ask her that too, whenever I’m in India, or over the phone, on those rare occasions without drama, why she stopped writing and there’s not just one reason. They are all valid, and depressingly so. There’s always the fear that what died in her might perish in me too. When I persist in my questioning, she quotes Kamala Das, something about a fever that came and went.

And to her credit, Kamala Das accepted at least one outcome of her fever in the poetry section of The Illustrated Weekly of India (now defunct) that she was curating:

“At 54 a, Lower Circular Road, Calcutta”. It’s a poem about someone who’s also in my poems. The difference being that the identity of the person is shielded in her work; it isn’t exploitative, like mine, but cathartic.

Her wrinkled face/holding in its folds/part of my own destiny is an indictment. The question in my question/unasked and diffused, however isn’t just aimed at the owner of the wrinkles, who’s Mother Teresa; it’s diffused in what is clear to me now was an effort, a chronicle of her responses to something society perceived as betrayal. It concerns the sadness of seeing an intellectual of the highest calibre renounce her gifts for a holy order.

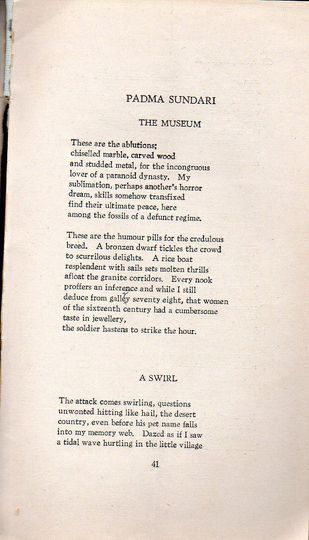

And in “THE MUSEUM”, another fevered creation, lines like this: Every nook/proffers an inference, offer me more insight into my mother’s sense of aesthetics, her perception of the exhibits in a museum, than any account outside of the poem; for instance, I remember little of the few excursions we’ve undertaken together-that trip to the Smithsonian; she’s just a photo in it, under a space capsule, and photos are great but they never reveal details like scurrilous delights or resplendency or deductions into the adornments of sixteenth century women to define a few memorable seconds of the interior. A poem like, “In The House of Lawyers” is an invaluable record of ancestry: caliphose-6x/from Grandfather’s homeo chest/or the Allahabad Law Journal, bound in leather.

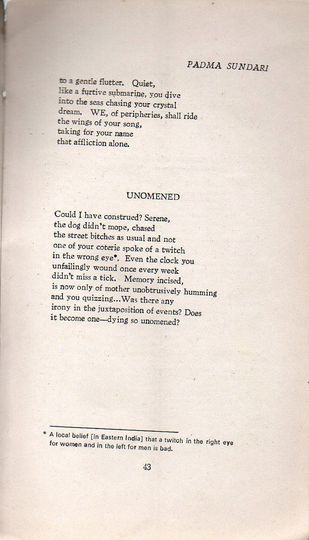

But in my opinion, the best of Padma Sundari’s oeuvre is the poem, “UNOMENED”.

It was so easy for me, when I’d first read it as a twenty year old, to dismiss the beginning, Could I have construed? for being cerebral and not the real deal; and now, I applaud her craft. ‘Construed’ is an unusual, startling verb, and it was masterful to position it at the end of the first line, in a dazzling complement to the title. The poem, which is mainly crafted around one familial death, actually refers to two. And elements, like the clock, seep from the first unomened demise into the next. The ending, ‘Does/ it become one— dying so unomened’?encapsulates for me her memory of many deaths and failings: the best friend, who, along with her family was crushed by a sixteen wheeler; a vicissitude that claimed her grandfather’s house— which, through its many retellings, has assumed in my mind a palatial proportion— and many other skeletal interpretations that the poet surely didn’t intend.

Her body of work now amounts to the few scans shared here,just enough to perhaps qualify as a dog-ear in the glorious history of Indian English Poetry. Sometimes, she jests that she merely needs another fifteen poems for a full length collection, and if I’d be willing to lend them to her. The last time she wrote a poem, she e-mailed it to me. It was her only work in more than a decade:a tribute to her favourite uncle who’d just died. And I probably never replied to her,or if I did, it was terse and professional, as an editor to a poet. A rejection note of sorts.

*

Add comment