This is the trail trod by Gurjala Ravinder as a worker of the Singareni Karmika Samakhya (SiKaSa). This path was forged by the coal miners, paved with the salt of their labour and the weight of their dreams. It is never easy to carve paths through lands untouched by the footprints of time when the path is rugged and unyielding. Along its length and breadth lie the struggles of workers who risked their lives, their warm blood nourishing the soil of resistance. The trudged path, heavy with the echoes of their courage, stands as a testament to the lives of martyrs.

Inside the choking depths of the earth, where darkness swallowed every breath, and the air hung heavy, miners waged strikes for air, light, water, safety, and even the most basic dignities of life. They fought for houses, medical care, and a better life outside the mines. They carried out militant activities demanding the regularisation of temporary jobs and the revision of wages. Behind all this, there was radical political consciousness, and there were meticulously crafted strategies. Ravinder played his part in all of them.

SiKaSa ignited a remarkable awareness in the lives of coal miners—who breathe and bleed coal. It altered the dynamics of human lives in the workers’ colonies. It reinforced human relationships. It turned innocent toilers into thinkers and activists. It lit flames of hope in the dark and lives under the rocky layers of coal and shale. SiKaSa set fire to the ‘Coal Belt.’ For the first time, it inspired working-class literature. New writers emerged from among the miners. Calloused hands that once gripped shovels now took up the pen. Coal cutters sculpted stories. Daily wage coal fillers turned their day-to-day struggles into songs. Boggu Porallo (In the Layers of Coal), Nalla Kaluvulu (Black Lotuses), Nalla Vajram (Black Diamond), and Banda Kinda Batukulu (Lives Beneath the Rocks) are some poignant and powerful works by the Singareni Coal workers.

Faced with the company’s exploitation, the betrayal of workers’ welfare by national trade unions—steeped in bankrupt trade unionism, including left-wing unions—and the rampant hooliganism inside the mines and workers’ colonies, the miners, under the leadership of radicals, forged diverse forms of struggle. Marked by both victories and defeats, the 56-day strike against wage cuts became a turning point for Singareni and the history of the entire working-class movement in the country. SiKaSa emerged as the unassailable leader of the coal workers in the coal mines, a beacon of resistance and solidarity.

All this transformed into literature, etching their struggles into the annals of history.

Allam Rajayya’s novel Siren amazingly captured the qualitative changes in miners’ lives, before the emergence of SiKaSa, portraying this transformation with remarkable depth. Tallulu Biddalu by Hussain narrates the intense political movement within the collieries against the backdrop of martyrs – Gangaram and Saroja, – Gajjela Lakshmamma’s children. P. Chand’s Veerudu weaves the life of Sammireddy, a man who burned like a pillar of live fire. These three novels have inscribed in blood the history of Singareni’s struggles, which stood as a beacon for the entire country. In this continuum emerged Ravinder’s Embers of Coal.

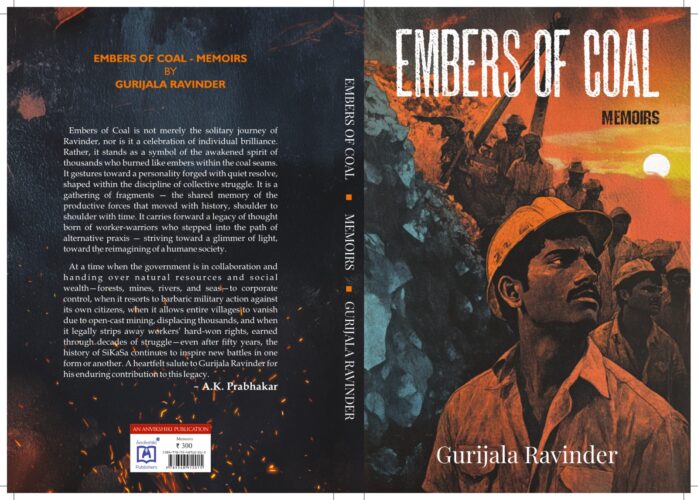

Though autobiographical, Embers of Coal remains a work of creative writing. Published in Telugu by Perspectives (2024), it is a remarkable feat that the book has been translated into English in the same year—a milestone in the publishing world.

Whether historical writing or an autobiographical sketch, a writer must have an objective, and well-defined perspective. Their worldview enables them to see history not as a collection of events but as a cohesive tapestry. A transparent world outlook provides clarity of vision and guides them on the right path. Ravinder’s life must be understood in this light. Then, his memories will not remain mere personal recollections, nor will his experiences be confined to individual incidents. They will become part of history, rooted in a specific time and place. They will take shape as the theoretical knowledge that guides political practice and serve as torches lighting the way for future generations. Ravinder’s memoirs, though written as fragments of memory, stand out in coal-mine literature because they meticulously record the firsthand experiences of activists who participated in the radical movement.

Ravinder began his life in the coal mines as a daily wage filler at the MK-4 Incline mine in Ramakrishnapur.

Under the guidance of the comrade Gajjela Gangaram, who sowed the seeds of militant workers’ struggle in Singareni, he absorbed political lessons. Under the leadership of Nalla Adireddy (Comrade Raghu), Katakam Sudarshan (Comrade Anand), and Sammireddy (Comrade Ramakant), he matured into a committed activist. Following in the footsteps of Hussain, he assumed leadership responsibilities within SiKaSa. From Ramakrishnapur and Mandamarri to Bellampalli, Srirampur, Godavarikhani, and even the open-cast mines of Manuguru, Ravinder helped ignite and spread the flames of SiKaSa’s resistance. He became the voice of the coal workers, a thorn in the side of the management, and was hunted by the police. Framed in false cases, he endured brutal repression. Forced into exile, he lived apart from his family, unable to return even when his father passed away—denied the chance to see him one last time. He faced severe torture in police lockups and spent more than a year in prison. Yet, through it all, he turned every moment into an opportunity to learn, grow, and deepen his understanding of the movement.

Amidst all this, Ravinder married his cousin Sarala, who was active in the Agricultural Workers’ Union. However, before they could even spend ten whole days together, Ravinder was imprisoned. Though he was eventually released on bail, the repression continued. Separated yet united in their commitment, the couple remained steadfast in their dedication to the movement. Against their wishes, a child was born when their decision to undergo family planning surgery failed. Their lives were so deeply intertwined with the movement that it became impossible to distinguish between personal and collective interests. When Ravinder’s father passed away, heavily pregnant Sarala braved the overflowing Maneru stream to pay her last respects. The image of Ravinder and his comrade quenching their thirst with filthy water from a murky pit under the scorching sun is equally poignant. Such moments are a stark reminder that revolution is no feast; they lay bare the harsh realities and sacrifices endured by countless activists.

Ravinder’s statement—that he and Sarala had to step away from full-time activism because the party did not approve their request—sparked debates. Should the needs of the party take precedence over individual emotions and thoughts? The question ignited discussions. Decisions, after all, are shaped by the circumstances of time and place, always with an eye toward the broader public interest. Ravinder’s words make it clear that he acknowledges this understanding. As time passes, perspectives evolve, and new meanings emerge. After spending eight years (1978–86) as a militant activist, Ravinder now places his Memoirs before the readers for judgment. The final verdict, as always, lies with the people.

Embers of Coal is not merely the solitary journey of Ravinder, nor is it a celebration of individual brilliance. Rather, it stands as a symbol of the awakened spirit of thousands who burned like embers within the coal seams. It gestures toward a personality forged with quiet resolve, shaped within the discipline of collective struggle. It is a gathering of fragments — the shared memory of the productive forces that moved with history, shoulder to shoulder with time. It carries forward a legacy of thought born of worker-warriors who stepped into the path of alternative praxis — striving toward a glimmer of light, toward the reimagining of a humane society.

At a time when the government is in collaboration and handing over natural resources and social wealth—forests, mines, rivers, and seas—to corporate control, when it resorts to barbaric military action against its own citizens, when it allows entire villages to vanish due to open-cast mining, displacing thousands, and when it legally strips away workers’ hard-won rights, earned through decades of struggle—even after fifty years, the history of SiKaSa continues to inspire new battles in one form or another. A heartfelt salute to Gurjala Ravinder for his enduring contribution to this legacy.

Translated by Vimal from Telugu

Thanks to SARANGA and to AK Prabhakar annaa for his foreword to my buk.. Every WRITER Sits his Place only.. but THE BOOK TRAVELS RAROUND The WORLD.. NOW THE WORLD KNOWS STRUGGLES Of SIKASA & their Sacrifices..

Wonderfully written ..analysis certainly helps those who wants to know the inner details ..hearty congratulations to both Prabhakar garu and the writer Ravindar garu

Mukundaramarao

Hyderabad