Their Urdu is fluent,

Elegiac poetry; expression of power.

Political and religious separation,

They are acquainted to the desolate hour.

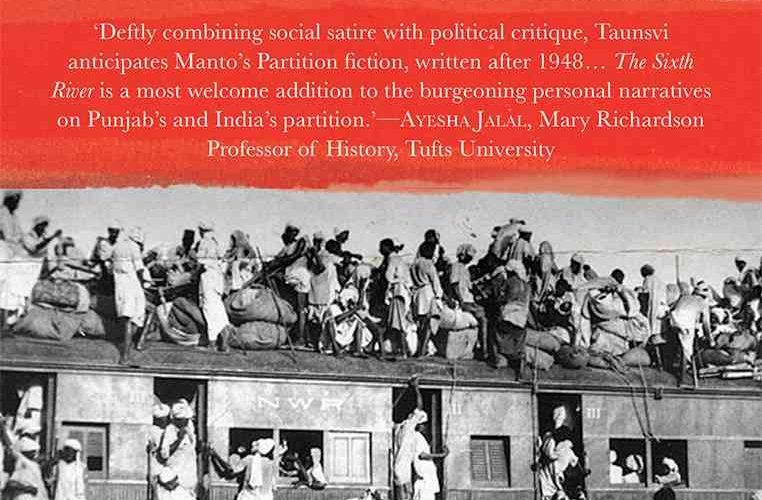

Fikr Taunsvi’s ‘Chhata Darya’, now known as ‘The Sixth River’, is one of its kind works around Partition. The stories are an integration of historical facts, and anecdotes. However, Fikr manages to make the reader experience these anecdotes, the violence, the disorientation, from an observer’s perspective, rather than that of a victim. Fikr is not seen pitying himself throughout the journal, rather he sounds almost curious about the events that occur around and to him during that period. This eye-witness account has been translated by Maaz Bin Bilal. He is the associate professor of literary studies at the Liberal Arts program provided by O.P. Jindal Global University. Maaz had already been popular as a poet, much like Fikr, for his formerly published book, Gazalnama: Poems from Delhi, Belfast, and Urdu. In fact, Maaz possesses Fikr’s artistic qualities, and his way with words.

As the translator, Maaz manages to familiarise the readers with Fikr’s narrative in his introduction. He has not only explained Fikr’s character and journey but has critically analysed the text for the readers. Maaz finds Fikr’s stories particularly interesting yet important, and describes translation as an act of service, as well as recovery. Maaz points out that one of the reasons he chose to translate The Sixth River was because of its relevance in today’s day and time. The sixth river according to Maaz, is not just another eye-witness account of partition, rather it highlights the engineering of the political structure which has led to communal complexities for decades now. “With regards to Chhata Darya and the parallels we see today, I thought it was a more valuable text in its politics and depiction of communal politics. Often people related with the Hindutva ideology in North see Urdu as a Muslim language or the language of Pakistan. Another reason I chose to translate this text was because Fikr himself comes from a Hindu background but still writes in Urdu. So, it is an attempt to put forward an Urdu text by a Hindu, who was a major literary figure of Urdu in independent India.”

Maaz himself is an admirer of the language, in his introduction Maaz argues that Urdu neither Hindu, nor Muslim. Fikr’s Sixth River is one of few works of partition which had been written in Urdu and is a non-political leader account, which also highlights the internal displacements during partition. Maaz’s family was internally displaced during partition, and Fikr’s description of internal partition during that period is something Maaz could relate to. Fikr also understood the challenges of being religiously different in a time raging with religion. “On my father’s side I am a Punjabi, in India when I say Punjabi a lot of people assume that either means a Hindu or a Sikh Punjabi. But I am in fact, from a muslim Punjabi family.” The more Maaz talks about Fikr and the text, the more similarities can be seen between both, Maaz and Fikr.

The sixth river displays the loss of land, people, lifestyle, and identity, but most of all it introduces religion as a mediator for a larger political agenda. However, Fikr’s outlook towards religion is contrary to the ‘engineered political structure’. Fikr is not seen blaming any dharam, be it Hinduism or Islam for the betrayals, violence, deaths, or political unrest. Rather, he blames the violent misdemeanours upon the adverse reality constructed for a larger political purpose. Even when his own friend murders his daughter and offers Fikr to take his child’s life out of guilt, Fikr forgives him and labels it as an act of intense rage because of the unfortunate circumstances. Maaz describes Fikr to be clear sighted about what instigates a riot, and that it was never Islam or Hinduism which caused this violence. Instead, Fikr blames the political leaders, politically guided local actors with mercenary interests, and a larger agenda at work. Maaz compares that to the present situation in our country, “It is a politically engineered structure to create riot like situations, to create discourse which reeds hatred and then ultimately is responsible for the kind of communal hatred that we see around us.” Maaz’s recent work, his poem, ‘Who Did It?’ incorporates a similar idea. He constantly asks the rhetoric question, ‘Who Did It?’ while referring to the situation during the first wave of the pandemic.

The call of the lapwing sounds at night, ‘who did it!’

On which detection must we alight, ‘who did it?’

The whole town was witness to the crime, nonetheless,

The haakim forces the victim: ‘Write – who did it!’

A plague is afoot, sifting through humanity,

Who spread it? Where’d it come? Is it not trite: who did it?

Where we go from here may scream to the skies

Of the bravery of all those who fight who did it.

Nature’s self-correction, the sins of the fathers,

Did a god will this to set aright who did it?

I am drunk on wine, and they are on power,

Who’ll adjudge who is wrong, who is right, who did it?

The rich live in isolation in large bungalows,

Abdul, who built that house, must fight who did it?

Deserts of loneliness, and ghettoes and camps,

Who put them there and set them alight, who did it?

Birds still chirp, humour persists, there’s laughter, oh, Maaz,

Do not write poetry from pain to spite who did it.

The sixth river is a metaphorical river of fire and blood which portrays the divisive rift created in the middle of Punjab by communal and imperial politics. But this is not the only metaphorical boundary in the text. Maaz believes that there exists a personal boundary in the text, one amongst friends, caused by the partition. The sudden transition into loss of trust, loss of belongingness, and ultimately loss of ones’ friends. “Lahore for him, as one reads in the Sixth River too, became the city of (composite) culture and the arts, intellectual inquiry, and creative and professional opportunity. But perhaps even more strongly, Lahore for Fikr was the place of friends, of his genteel society, camaraderie and social etiquette.” Fikr delays his departure from Lahor, until he has been betrayed by Mumtaz Mufti, whom he considered to be a well-wisher and friend. It is only then that Fikr feels he does not belong in Lahore anymore, and leaves to find his new identity. Maaz explains how this boundary still exists during modern times. It is unfortunate but everyone has drawn these boundaries with someone in the past few years, “That is what we see as the heart of the tragedy in Sixth River that Fikr has to leave Lahore, not because of the geo-political boundaries but the personal boundaries as a result of the geo-political boundaries, it is his friend’s betrayal that eventually makes him leave Lahore. And I see that happening around me, in my own life, that personal relations are increasingly getting affected by this overall circulation of hate which is politically engineered.”

India had been in a catastrophe much before the pandemic. However, the awareness around this political, social, and economic predicament has increased since intellectuals, artists, poets, philosophers have started creating and publishing pieces during crucial timelines. This brings us to the time old debate on the role of art that is inspired by tragedy. Fikr Taunsvi’s ‘The Sixth River’ with its unique style of writing, finds a way into this artistic sphere. However, a lot of times creating art while the world around is collapsing, can be considered problematic and unnecessary. It may indicate detachment from the actual tragedy and show opportunist behaviour. Such work is argued to be distant from reality and insignificant in making a difference. Maaz’s introduction mentions Fikr’s ability to “step away from the immediate violence all around him to rationally interrogate causality.”

Despite all accusations about detachment, art and literature is a space to vent and express anxiety, and documentation of crucial timelines in history becomes a complimentary benefit. Maaz argues that the section where Fikr questions art, elevates the debate beyond art to culture or civilisation itself. “Art is not just history, it is a comment, a response to history perhaps. When violence does take over, reading a poem to a gun pointed at you will not block the bullet, art does not do that, neither can culture or civilisation. But once that immediate violence is over, art and culture will help you make some sense of it. It will make that violence and loss bearable; it will help you cope. It will make life worth living.” Art is also considered to be an Artist’s escape from the merciless reality. Majority of arguments against art and tragedy are based on prejudice and heavy judgement on the selfish nature of documentation during crisis. “For the artist, it is also a means to make sense of the world, to respond to tragedies, be it personal, political, or civilisational. It is important for the artist to find a way that they can connect with, that expresses their agony, their discomfort. It helps elevate their own other trauma, anxiety, concern, by things they can enjoy and appreciate, that even entertain them sometimes, that allows them escape.”, Maaz adds. Maaz argues that Art is not merely an act of therapy but also an important source of criticism. He says, “it is not just a means to vent but also to criticise. It is voicing the people’s voice. For example, Parul Khakhar’s poem mentions how Ganga has become a hearse carrying dead bodies in the King’s ideal realm (Ram-Raj). It criticises the regime and call out the leaders. This poem garnered twenty-eight thousand hate tweets because it was against the government, that shows the kind of impact art can have.” The poem also saw a great deal of positive reaction because there were so many people who could relate their loss to this poem. “This poem gives those people voice. Artists are not guilty of negligence; they do what they can. A lot of artists are social activists, their art is activistic and then they do other things to help as well.”, Maaz adds.

In Maaz we can see glimpses of Fikr. Fikr’s curiosity and Maaz’s eagerness to navigate through tragedy while experiencing it are surprisingly alike. They hold the artistic proficiency to create both, emotionally meaningful and socially relevant pieces. Maaz is as fierce and fearless as Fikr in calling out a politically corrupt structure. Both their works are capable of describing pain, while maintaining the serendipity of literature. Maaz and Fikr are critics of politics and society, but they are also admirers of civilisation and culture. Fikr values his camaraderie, and Maaz has years of experience and work to show on themes of friendship. The alikeness of their ideologies and talents is uncanny but it comes as a blessing to the readers.

*

Very interesting. I was particularly struck by the writer’s desire to see similarities between the translator (Maaz) and the original author (Taunsvi). That they share similar concerns. It’s ok even if they don’t, although in this instance they do! A translator can enjoy his/her distance from the original work.

Conversely, the term ‘sixth river’ is impactful. It only proves that the partition is a dynamic history. Not bound by eras and historical pasts alone.

The copy of the essay here, however, would have benefited from some editing. Thanks, though, for introducing us to an important work.