On Thursday, February 17, from 7-9 PM, I attended an event titled “Brooklyn Reads: Bitter with Akwaeke Emezi” at the Brooklyn Museum. Despite living in New York City for the past four years, I had never before visited the Brooklyn Museum. Nor had I read any work of Akwaeke Emezi’s in its entirety. Years ago, I had picked up Emezi’s debut novel, Freshwater, read perhaps ten pages of it, and put it back down again, not for any particular reason, but with the intention to restart and finish it at a later point.

That evening, I was joined by a friend who had similarly never read a text by Emezi. My friend had only bought a ticket to accompany her roommate, who was in fact interested in Emezi’s work, but due to an unexpected conflict on the day the roommate was no longer able to go, thus leaving behind a free ticket that was then offered to me. Had I tried to master the waves of my life as meticulously as I normally did, I would not have ended up at the Brooklyn Museum on that particular day, at that particular time.

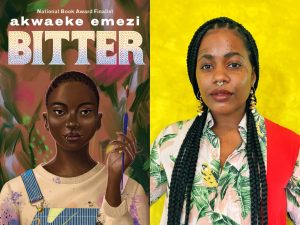

Akwaeke Emezi is a Nigerian-born English-language author who is only thirty-four years old, but has already written three literary fiction novels (Freshwater, The Death of Vivek Oji, You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty), two young adult novels (Pet and Bitter), one memoir (Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir) and one poetry collection (Content Warning: Everything). Bitter was published only two days prior to the event, and serves as a prequel to Pet, Emezi’s earlier YA novel. It follows a young protagonist, the eponymous Bitter (a transgender black girl), as she wrestles with the dilemma of participating in the frontline activism occurring in her town or remaining sequestered in her art studio.

The event followed the typical contours of a book talk: Emezi read a selection from Bitter, was then joined by Nic Stone, another YA author, for a conversation, before the audience lined up at standing microphones to ask Emezi questions. The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Auditorium, where the event took place, seats 415 people, and has two floors. Craning my head around during the event, I spotted a few empty seats here and there—but only a few.

This was the first literary event that I had attended since the pandemic began to wane in America. The other two pre-pandemic book talks that remain imprinted in my memory were for authors Jeffrey Eugenides in 2018, and Sally Rooney in 2019, both of which occurred in my first year of college in New York City. Those events were set at bookshops—the Strand and McNally Jackson, respectively—and neither had the Lenape land acknowledgement, nor American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter working throughout the talk, as “Brooklyn Reads: Bitter with Akwaeke Emezi” did. Eugenides and Rooney were also authors whose work gave shape to my adolescence, and in spite of the expansion of my reading life since then, I can still quote some of their sentences from memory.

But beyond just my own relationship to the literature, the tenor of Emezi’s event was so much more personal than any other literary event I’d thus far attended: I learned more about Emezi’s life from this event than I could have possibly anticipated. Emezi referred often to a period in their life that they termed their “asshole twenties” and the growth that they experienced from that period, especially after exiting a childhood of abuse, homophobia, and transphobia. They explained how the writing of Bitter and their forthcoming poetry collection Content Warning: Everything, took place at moments of intense suicidality and prolonged physical disability. They offered advice to the audience on how to set boundaries in close relationships, and how to practice and prioritize self-care in ways specific to black people. None of this conversation was unwarranted; it was entirely in response to the questions that the audience members asked Emezi, and Emezi always answered with care and grace, taking care to draw parallels between their life and Bitter’s characters, who similarly struggle with questions of race, class, survival, and revolution.

Sitting in that darkened auditorium, I wondered: fundamentally, is a “book talk” purely a promotional invention? Of course, the ultimate purpose of a book talk at a bookstore is to generate publicity and sales for the author and the store by hosting an intellectual conversation. At a public space like the Brooklyn Museum, though, was the same dynamic at play? What’s more, was the intimacy of the conversation unfolding before me part of this potential ploy? (One audience member, standing at the microphone, mentioned that they had a gift that they wanted to give to Emezi after the talk concluded). People are likelier to buy an author’s book if they feel they have a relationship to the author, regardless of how one-sided that relationship actually is.

At the same time, the publication of Bitter, in conjunction with its companion YA novel, Pet, seemed to give rise to a shared feeling among the majority-adult audience: the desire to have had this novel in their own adolescence, to give language and guidance to lived experiences they hadn’t yet known were shared. The event was hardly just about Bitter. It transcended that, expanding to questions of how to navigate a world hateful to black people, trans people, queer people. And why was I taken aback by that, if I believe that a book ought not to exist in a vacuum, that it ought to have bearing on real human lives?

After the event concluded, my friend and I wandered around the floors of the Brooklyn Museum that were still open. We wanted to look at an exhibit called “Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams”, but it was closed, so we instead meandered towards “The Slipstream: Reflection, Resilience, and Resistance in the Art of Our Time”, an exhibit of art ranging from the 1960s to the contemporary era that addressed the issues raised by the pandemic. We sat in a sequestered nook and, in silence, watched several animated films by William Kentridge, a South African artist whose major themes are capitalism and industrialization. As we exited, my friend showed me a quote from Emezi that she’d written down: “We will not see the world we want in our lifetime.”

*

I cannot express how much I appreciate your work . What an observant and thoughtful piece.