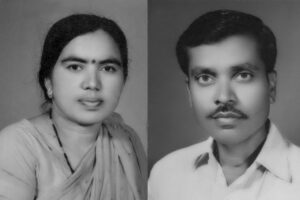

I miss my up-casting, feminist grandmother.

మేము రెడ్డోళ్ళము – This is how my paternal grandmother, Late Akula Lalitha Bai introduced our family in front of strangers. We are not Reddy though but she had that confidence of a dominant caste woman asserting her caste with no qualms – like a Reddy. She was fair complexioned and stood tall. The strangers had no choice but to bestow social privileges on her accordingly. Her real confidence however came from her education and employment achievements not from her caste.

She was a 5th grade graduate from a Telugu medium school in the late 1930s from Hanamkonda, the highest degree offered in a town of Telangana in the Telugu medium domain. One had to go to the city of Hyderabad to continue on to middle and high schools. After a few years of graduation, she got employed as a primary school teacher in Nizam’s government services.

She lived during the time the last Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali Khan had started advocating education and employment for Hyderabad’s woman citizenry. The Nizam was a late-moderniser in general when compared to the neighbouring Madras, Bombay and Travancore Presidencies (former two British administered and a Princely state). A moderniser he was, nevertheless. دیر آئے دورست آئے (better late than never)

Her real caste was “Munnuru Kapu”. It stands for a grouping of 300 (read “polluted”) sub-castes from intermarriages between non-landed Shudra castes and the landed Shudra dominant caste – Kapu. In Hyderabadi Dakhni they were teased as “dhai-sou pachas” literally meaning “250+50”, a dig on their upward mobility in society via proximity to the Kapu-caste. The Sanskrit meaning for the surname “Akula” is “without a caste or lineage”. Their ancestry traces back to migration from North India into Deccan specialising in land dispute settlements. That explains the intergenerational proximity to landed castes.

My grandmother preferred the up-casted “Reddy” identity however, a privilege-title for landed caste. It didn’t seem to matter to her that her family hardly owed any land though. Perhaps this real caste identity came with too much historical baggage. Only she knew the real reason. One thing was for sure that she looked the part and felt the part of a దొరసాని (dorasani), a dominant caste noblewoman.

This made-up “Reddy” identity came in handy. She used it for simple privileges in life like to jump the cinema ticket line on the first day first show (6pm) of a new Telugu film – by making small talk with upper-caste looking women ahead in the line and merging with them. It was that harmless. It got the job done. That doesn’t mean she would hesitate in capitalising on the free labor or cheap labor from lower caste domestic workers and even strangers when the opportunity arose. She was a gainfully employed woman, stylishly dressed with the best of saris and jewellery who commanded attention and respect, often translated into servitude, wherever she went.

My grandfather جناب Late Tulasi Venkata Narayana on the other hand was a 7th grade graduate from an Urdu medium school – the highest degree in town in his domain. He also got employed as an Urdu teacher in a government primary and middle Urdu medium school. He later graduated 10th grade from Hyderabad. He wrote Urdu poetry for Siasat and Rehnuma E Deccan weeklies under a pen name – Kiran and attended Urdu mushairahs.

Needless to say they both were stars, a power-couple in their caste and class biradaris. It seemed they could never go wrong, that is, unless the society betrayed them.

Despite being educated and employed, my grandparents made a hasty decision by marrying-off their daughter very early into a troublesome household. The matchmakers made a big deal of a certain educated and employed son-in-law prospect from a “progressive” Lingayat family. It turned out they were anything but progressive.

They didn’t quite respect my grandmother’s freedom of employment, her managing her own income, her agency in decision-making in family matters etc. The culture of intermingling of school staff between genders and religions apparently was also a major issue. Moreover, the elder of her two sons, my father, married the love of his life, my mother, a mixed-caste Christian neighbour, daughter of a WWII veteran father and an English teacher mother. Too radical for the 1970s and that too in a town.

These controversial freedoms my grandparents had to navigate and negotiate with caused the son-in-law’s family too much anxiety to the extent they kept my aunt, my father’s sister, isolated from her maternal home. This isolation from her daughter broke my grandmother. It shattered her and it became a lifelong-sadness. The whole family including my father and his brother, my uncle, were also affected. My father preferred a distance but my uncle became the bearer of humiliation during his several attempts to address the social isolation of my aunt.

On one side was my mother, the daughter-in-law, a B.A, B.Ed graduate with bright job prospects from a progressive Christian family. On the other side was her daughter who got married into a wrong family and was robbed off an opportunity to appear for government Teacher’s recruitment exam. The hall-ticket was also ready but she was not allowed to appear for the exam. She could have also become a teacher and accessed the same social and financial freedoms my grandmother and my mother did.

My mother soon got employed as a social welfare development officer working for the state. This contrast was too much of a reality check for my grandmother on the inequity among women in our society.

Moreover my grandfather wasn’t an easy man to put up with. He was highly individualistic, opinionated and financially conservative. My grandmother didn’t quite see eye-to-eye on many things with him and never hesitated to quarrel with him on disagreements. She used to dilute curries with water and serve him after he got drunk and insisted on being served dinner as a husband’s right and a wife’s duty. Alcohol became his lifelong-vice that contributed greatly to their overall loveless marriage, very typical of Telangana. My father was the only person my grandmother was emotionally attached to.

In order to cope with her life-sorrows she became a Sathoshi-Mata devotee. I would be lying if I said that things were always smooth between the Hindu mother-in-law, my grandmother and the Christian daughter-in-law, my mother, both coming from different castes and religions. They took time – decades – to come to terms with and to develop mutual respect when they eventually could see that they both were women of their own making, despite all the differences.

My grandmother also kept her interest alive in watching movies at cinema halls and I was blessed to accompany her a few times. The nearest cinema hall from our home was “Ashoka Talkies”, a swift 20 min walk. We would take a short cut that went through the ruins of Hanamkonda fort outer-gate remnants and also passed through the Dargah of a 17th century local Sufi saint, Hazrath Abdul Nabi Shah Saheb.

She would hold my hand and we would circumambulate the Durgah together a few times, like in Hindu temples. The mutawwali recognised her as a regular patron and indulged in khair-khairiyat talk. She would offer her respects and make mannats that I knew were almost always about the welfare of her daughter’s family.

There was no God left to be approached. Later in life, she would have prayer requests for my mother and maternal grandmother to Jesus for the well-being of her daughter and daughter’s children – a daughter my age and a son the age of my younger sister.

The social isolation of my aunt was broken with an involuntary intervention – abandonment of my aunt by her husband upon her first pregnancy complications. My aunt ended up living with us for several years after suffering with depression. During that time, my grandmother made it her life-mission to ensure quality healthcare for my aunt and quality education and social freedoms to her daughter’s daughter, at par with what I enjoyed as a boy. This was her path to atonement, her relief from her grief.

She turned into a fierce feminist as life passed by. She would not just wish or encourage but curated progressive life experiences for her daughter’s daughter, my cousin. She happily consented to my cousin’s love interest and even facilitating her marriage to a Reddy – a real Reddy, of course!

Later in life when she started living with us with our maternal grandparents as neighbours, she saw with her own eyes the rigid caste barriers that she grew up with being broken almost on a daily basis. These included treating domestic workers with dignity, mingling with them and eating together, attending their life events and inviting them for ours, not expecting free or cheap labor, supporting inter-caste and inter-religion marriages etc. This was an alien territory for her, and she took her own time processing such radical social changes.

My two Ashraf Muslim friends were spared because she knew they came from “reputable” caste-class backgrounds but my other friends, BC Hindu and Christian, were subjected to occasional checks and balances. Things smoothed out after she realised we had all become lifelong friends and support system to each other regardless of caste and religion.

If there is one story from her life that truly captures her courage and grit, it is this one – soon after her marriage to my grandfather, his relatives and friends started mocking him for letting his wife work. They got to his head, and he offered her a choice between their marriage and her job in a heated argument one night. She chose her job. The next morning, he quietly dropped her at her school on his bicycle before going to his and this continued until she hired a rickshaw-transport to her work.

There was this lingering sadness in her eyes for as long as she lived. Only after her demise could I fully process her complicated life story, well into my adulthood. Somewhere in this remembrance is a eulogy for her that I never got to pen down immediately after her death. Its been 6 years since her passing away. A eulogy too late but دیر آئے دورست آئے

*

Beautiful writtenBeautiful written Moses brings her to life before us!

Very interesting, Beautifully written