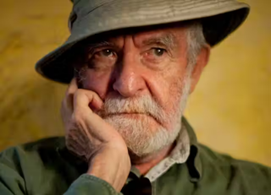

These were the words of a black child chosen to be inscribed on his gravestone by Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard, who passed away on the 8th of March this year. He was South Africa’s most important and prolific playwright with thirty eight plays, many film scripts, LifeTime Achievement Awards and more than 20 honorary degrees to his credit. He was the first South African playwright to enjoy an international reputation. Fugard also served as the adjunct professor of play writing, acting and directing in the Department of Theatre and Dance at the University of California, San Diego.

Born on 11 June 1932 on a farm near Middleburg, Cape Province ― a village in the semi desert Karoo region of South Africa, a place of enforced intimacy and depressing squalor, Fugard was an artist of intense integrity and moral commitment. Fugard attended Port Elizabeth Technical College, left home and hitchhiked to North Africa with a friend. He became “keenly aware of the injustices of apartheid” and befriended local anti-apartheid activists – an experience that shaped his future work.

The name of Athol Fugard (pronounced few-gard) is synonymous with the South African theatre. Starting his career on conventional dramatic lines, Fugard has grown to become the major South African playwright registering his name along with the world famous playwrights like Arthur Miller, Tom Stoppard, Harold Pinter, Edward Albee, August Wilson and David Hare, with plays which mark his strong resentment as a white liberal humanist.

The South African writers experienced torture, imprisonment, exile and other common punishments imposed on them by the governments. Several writers – poets and novelists were banned, sent into exile or were forced to meet their own death. If Dennis Brutus, Ezekiel Mphahlele, Bloke Modisane, Alex la Guma, Mazisi Kunene, Lewis Nkosi were sent into exile, Can Themba was slowly strangled to death. The works of several white writers such as Nadine Gordimer, Andre’ Brink and Athol Fugard were banned from public reading and performance. His house was searched frequently and draft copies of his plays were taken away many times.

As felt by Gordimer, “politics is not just a climate,” but to borrow the phrase of Irwing Howe – “politics is fate in South Africa and it has choked the other implications of the South African writing”.

The South African theatre with its “oral” and “kinetic” products of performance culture started developing from the 1930s. The real theatre experience evolved from Jazz performances during the 1940s. The establishment of the National Theatre Organisation (NTO) provided an outlet for local writing with the contributions of W.A. de Klerk, Gerhord Beukes, Uys Krige, Guy Butler, James Ambrose Brown, N.P.Van vyk Louw and others. The 1950s witnessed a “renaissance of English drama” in South Africa. There were plays by Alan Paton, James Ambrose Brown and Lewis Sowden and from the township by Gibson Kente and Sam Mbanghwane. In the 1960s Fugard formed Serpent Players – a group that consisted of black worker – players like John Kani and Winston Ntshona who earned their living as teachers, clerks and industrial workers. In the mode of Jergy Grotowsky’s poor theatre , Fugard created plays reflecting the conditions of the black townships using the biographical tragedies of the worker-players.

There were several Acts like CopyRight Act (1965), Group Areas Act (1965) etc., “which imposed control on the writers.”

From 1976 to 1989, theatre acted as a weapon against the government. Zakes Mda, Matsumela Manaka, Maishe Mapanya, Kessie Govinder, Muthal Naidoo also produced their works. Of all, it was Athol Fugard that made the “personal” dominate over the “political” without negating, at the same time, the political content as the focus of his attention.

Although blacks used to visit theatres before the National Party’s victory in 1948, they sat in separate areas; by the early 1960s, they were prohibited by law from attending performances altogether, and the “mixed” casts were forbidden. Fugard’s collaborative theatre practice challenged all this.

Rejecting the label of a “political playwright”, and speaking about his status as a “story teller”, Fugard affirms that he always “wanted to celebrate” the “forgiving and understanding” nature of “the South African situation” exhibited through the “generous” gesture of Nelson Mandela. He says:

That is why (this) perception of myself as a political writer disturbs me. An attitude like that closes off an individual to an important thing I have tried to do. I became conscious, as I was thinking about talking to you today and as I was looking back over my plays, that in addition to all the judgements, the condemnations, the angers, the outrages, the whatever else I have expressed, I’ve tried to celebrate the human spirit- its capacity to create, its capacity to endure, its capacity to forgive, its capacity to love, even though every conceivable barrier is set up to thwart the act of loving.

The Notebooks of Fugard record several such images, ideas, opinions, observations, comments and even his feelings which form the genesis for most of his plays. The “notebooks” reveal both Fugard’s love of the physical beauty of his homeland and an eye and ear sensitive to the events around him. The first entry in his notebook proved to be the genesis of The Blood Knot (1961). The themes of other works include the acceptance of responsibility for one’s life, the recovery of past memories that lead to affirmation of the present, and the heightening of individual consciousness.

Fugard provided world theatre with a major sequence of plays, mostly set in South Africa, and for the most part reflecting, or influenced by the politics of apartheid and its legacy. Most of his works were written for a South African audience and presume an understanding of that society. He speaks passionately about South Africa and its people. Fugard’s work as an artist has its persistent focus on the disenfranchised, the dispossessed, and upon the ‘ordinary people’ of his region. Though he started as a regional writer, his works have universal significance and appeal. His commitment to the theatre is total and it involved a willingness to take risks: not only on the personal level, but with a “triple psychology” (The Paris Review, 1989) – as a working playwright, director and actor, and at times when the rulers of his country seemed hell-bent on destroying, not only serious opposition, but all signs of independent thought. All his plays stood as challenging statements to the Acts initiated during Apartheid reflecting the traumatic conditions with both black and white actors on the same stage. Even during the post-apartheid conditions Fugard continued writing expressing his faith for coordination and the potential of human ability to celebrate the capacity for forgiving and for loving overcoming the barriers of antagonism and racial disorder. Plays like Playland and Valley Song showcase this.

Fugard’s contribution is noteworthy not just because he was the most widely published and produced playwright from South Africa but rather because he was the first to create on stage a fully colloquial South African English, as opposed to the self-conscious literariness that usually affects writers. Shaped by the Afrikaans that many of his characters would possibly speak more readily than English, especially The Blood Knot (1961), Hello and Goodbye (1965) and Boesman and Lena (1969), the mature plays of Fugard created a South African idiom that could be national, local, and intimate all at once.

As Loren Kruger, the Professor of English and comparative Literature at the University of Chicago observes, “the dramatic and theatrical idiom of Fugard’s solo literary work can be described as a synthesis of the scripts of domestic drama, existentialism and anti-apartheid testimony. What Fugard did was to make ‘political theatre in the western mode’ visible, available, and ultimately legitimate to a degree impossible for the small, beleaguered interracial groups associated with liberals or communists in the 1930s and 1940s” .

Along with the influences from Kierkegaard and Sartre, in Camus, Fugard found a kindred spirit for his world-view and in Beckett he found a dramaturgy of maximum import with minimum theatrical outlay. If Time magazine calls Fugard “the greatest active playwright in the English-speaking world”, New York Times praises him as “the greatest playwright writing in English since Shakespeare.”

While retaining the liberal stance, Fugard produced complex plays projecting both the political situations and the existential angst of human beings. Athol Fugard, the humanitarian and challenging voice of the South African theatre, believes in the power of words, which he feels are implicitly explosive. He feels that ‘words are more powerful to create the right ambience’ in the hearts of the rulers and several of his plays illustrate his conviction.

As observed by Alan Shelly, “Fugard is the consummate man of the theatre, who, in addition to supplying words, has directed most of all his own plays, and acted in many of them, and knows very well how to keep his audience engaged”.

*

Add comment