As I picked up The Fern Gatherers Association, I was charmed by the aesthetics of this book. Red River Press, the publisher, has done a wonderful job with this one. The title itself is intriguing. Ferns, one of the oldest living forms, are an enigma to themselves, nature’s own poetry. They are rich in variety and prolific in growth in the tropics. They are also the link between a world past and the world present. The poems in this anthology too are rich in a variety of mood, tone, style, diction, and of course, metaphors. Poet Howard Nemerov had once said, “poetry is an art of naming and this naming is done by story-telling and by metaphorical approximation and refinement”. This anthology tells us beautiful stories – of life, of the everyday things around us that lose their mundanity through the poet’s eyes. In poet Sekhar Banerjee’s eco-humanist world, red letterboxes hang on trees (Dead Letter Boxes) or the poet wants to turn into millipedes and burrow deep into the pillow away from the sun (Paraffin). Humans live in a world of close dialogue with nature, they are one with it, an entity in the vast corpus of being, not the master

My feet are roots – I carry my roots wherever I go

and I keep slush, the raindrops, the black clouds

in my head and my shirt pocket

(Lohagarh stanzas)

Like the ferns, the poet is also establishing a connection – between the old world of letters and post boxes and this world of virtual communication, between the hills and tea gardens of Bhutan and North Bengal and the plains, the city of Kolkata. Between the living and dead too – “You are now older than your dead brothers; and still younger/ than your long-gone parents/ Now your son and daughter…” (A Large Family). The world of Fern Gatherers’ Association is life-affirming, and death, though never too far, is just a part. Life is playful, a series of metaphors –

“Warmth is the contour of heat

History is a contour of us

A kettle is an unborn fire

Fire is a relative of the sun

The sun is the stove of the universe (Book of Tea)

This month’s column Poetspeak spotlights poet Sekhar Banerjee and engages him in a conversation around his latest anthology of poetry The Fern Gatherers’ Association. The conversation happened over a week via WhatsApp chat where the poet expressed his feelings and ideas behind the composition of this anthology.

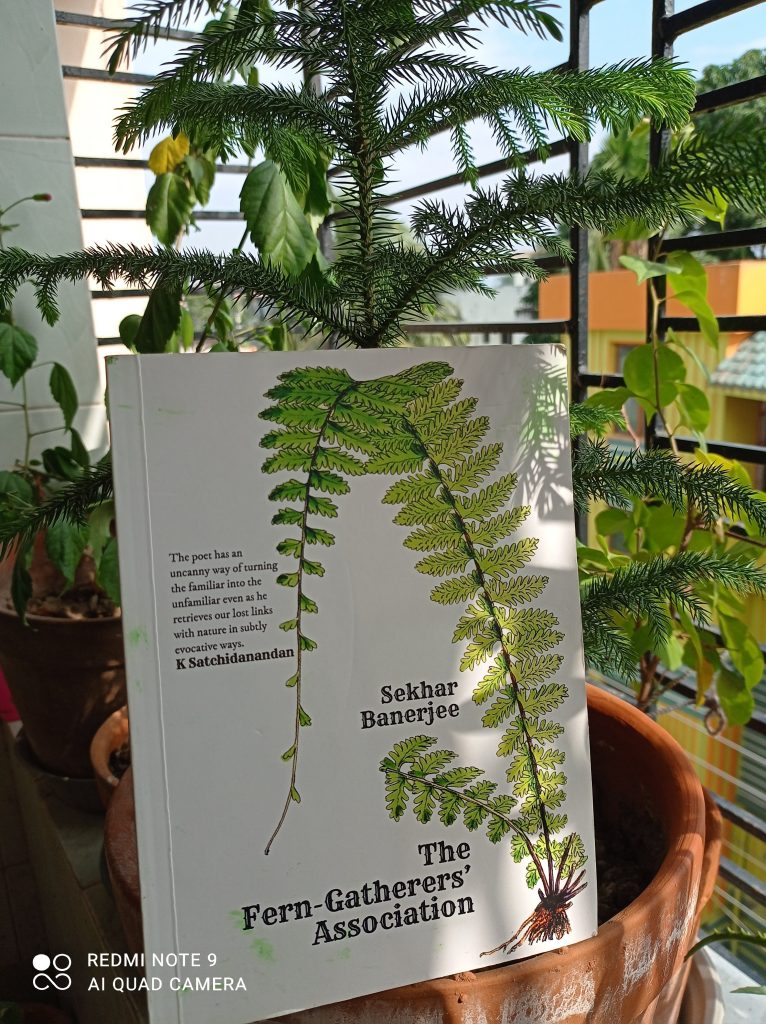

NS – Let’s begin from the beginning. Cover art and title always intrigue me as they are the first interaction with the work. What struck me was the beautiful greenness of the cover. It would be great if you could share with us what prompted this title and such a cover?

SB – Thank you for asking, Nabanita. The Fern-Gatherers’ Association, I know, is a rather unusual name for a poetry book. I was born in the tea region of the northern part of Bengal where the ferns grow abundantly. It is much like going back to my roots through the title. However, I always believe in minimalism in poetry and re-establishing our lost link with nature in life.

The white background signifies minimalism in life and the greenness is our lost link with nature that we still carry in our collective unconscious.

NS – Yes, I can see the poems in this anthology reflect what you just explained. You know, your last response preempts my next question. If a word could describe an anthology, I would say this is an amazingly green anthology. Your tea region roots partly answer for that. But somewhere your city life intrudes as well. How do you look at both the experiences and how do you assimilate them in your writings?

SB – It’s a very essential question, Nabanita. It’s true that our early life experiences shape up a part of our thinking and create our core vocabulary. My poems are replete with woods and mountains as I have lived in the tea region of Bengal and Bhutan as well. However, they are a facade for expressing my emotions and realizations or absence of it because I believe that humans should live in sync with nature, not going beyond what is still an organic journey for all of us.

To me, urbanity is a concept, not a particular way of living in an area crowded with superstructures or mountains and tea gardens. The basic life experiences – pain, pleasure, grief, enmity, loneliness, death, in absolute terms, remain the same. Some are subtle, some pronounced.

This dichotomy and oneness of our existence haunts me and exasperates me more than anything else. And I keep on using more similes, more allegories, more metaphors from nature intentionally while living a ‘ city life ‘ – whatever that means. Life is a more appropriate term, I presume.

Now there is a craze for ‘ecopoetics’. But poetry is and always will remain dependent on our ecosystem and our immediate environment as long as we are organic beings and not straight-jacketed into some economy driven philosophy of life. Light posts might have replaced trees and multistoried buildings might have replaced the singular home and metaphors and similes might have changed accordingly, but our raw emotions as human beings remain the same in all places alike. That’s why poetry is universal.

NS – You know, this brings to my mind a host of poets like Mamang Dai, Easterine Kire, Esther Syiem, Robin Ngamgom, in whose poems nature is a living, thriving entity. I find your anthology The Fern Gatherers association to be in a similar tradition. Is this a coincidence or were you consciously being a part of a tradition?

SB – Geographically speaking, the northern reaches of Bengal is more attuned to the northeast. This might be one reason for looking at things somewhat similarly. However, this is not a conscious endeavour. On the other hand, this particular way of looking at life and poetry resonates in the works of some of my favourite poets, say Elizabeth Bishop, and Wallace Stevens or Adam Zagajewski. However, my favourite list of poets also includes John Ashbery.

NS – That speaks a lot about the versatility that we meet in this anthology!

As I was reading the poems, I realised that letters, postboxes, addresses – these references kept recurring. Is this a nostalgia for a more tangible past when the idea of ‘touch and feel’ was important?

SB – That’s a very good question. Symbols and agents of communication come as a recurring theme in my poems simply because I miss the effort and the feelings associated with the past methods of communication. The yearning for more meaningful and sensitive communication brings back the good old ‘ touch and feel ‘ days when our limitations in communication compelled us to attach more values and permanence to it. However, I have other reasons to dig up those symbols because I stayed in an almost cut off place in the hills of southern Bhutan for four years as a Government teacher and the postman was the only angel we would look for every evening.

NS – No wonder there are so many references to the postman and letters. My favourite one is-

Letters slowly pile up

month after month, as if,

they are my unopened sleep at night

as if, they are my last days,

in exile (Letters Sorting Home)

I also find it interesting, the way you look at the city in your city poems – the concrete and the natural blend in a beautiful collage. What makes you look at the city like this?

SB – I feel that the city is a necessity however much we pine for Arcadia. We need cities to grow otherwise the community life in surrounding small places will eat up an individual’s effort to be what s/he is. But cities need to be more organic, more humane in their approach to their inhabitants and overall environment than a mechanical superstructure created for the fittest who can survive. That’s like another jungle with town planning. I try to find a balance in my poems.

NS – That is true. To be organic seems to be the mantra towards more sustainable living that the cities are moving away from. Thank you for such well thought out responses. I am sure The Fern-Gatherers’ Association is going to win many hearts. Now, a couple of questions about you and poetry in general.

As a bilingual poet, do you think there’s a difference in terms of subject, theme, etc when you write in Bangla and in English?

SB – Yes, I have several books in Bangla as well. People of my generation used to be bi-linguals as a colonial legacy and subsequent surge of nationalism. I try to bear this legacy. Linguistically and sociologically, these two are different worlds altogether. However, the emotions are the same in every language, only the diction of expressing it differs vastly.

NS – And finally, what does poetry mean to you?

SB – Poetry is a kind of therapeutic and spiritual experience to me, the only way to express the world as I perceive it and a notebook on how I lived.

NS – Thanks for this enriching conversation and for penning such a beautiful anthology. I wish you the very best. I would like to close with a few lines from this anthology that speaks of loss and companionship in deep communion with nature. This anthology is replete with many such poignant imageries.

In the evening, I see a lonely human figure going

down the valley with the Tibetan horse with blue fog

following

loss

in a strange language they converse

(Goethals Football Field, Kurseong)

*

Add comment