I would like to start with the poem, “Ponnie looks back”, by Lakshmi Kannan, as a good way to Mind the Map, though it covers only a portion of the map, it tells us the story of the entire South Asia.

“I was their inerasable Memory. I just flowed on, and on, until one day. I noted how differently the people were dressed now. Some of them

were crude, their voices loud, their language rude. They sat around large tables, shouted at each other and referred to me dryly as ‘the Kaveri dispute’, wrenching my waters apart to broker a deal between the Kannada land and the Tamil land.

They forget that I have always washed the two lands impartially, equally, like a good mother that I am. I have seen it all. As a liquid, flowing time, I am condemned to see it all, wearily. I have a memory now that swells and sags with the sorrowful weight of a land where people have turned quarrelsome and partisan.

My journey toward the sea is weighted down by memories of the lives of Kannagi, Kovalan and Madhavi on my banks in Kaaveri Poompattinam, known as Poompuhar. The tragic grandeur of their lives is immortalized in the epic Silappadikaram by Ilango, and in Manimekalai by Chitthalai Chatthanaar. I have offered solace to this starcrossed couple and now I must join my mother at the Bay of Bengal.

Until I merged with my mother, the ocean, I was your own Ponni”

“Ponni” has many meanings, in different regions within this map, in addition to the name for the river Kaveri. It could also mean a seeker of wisdom, and all the poets we come across in this anthology are seekers of wisdom and also guide the readers to seek wisdom through these poems.

We need to follow up with another poem about a river, by Mamang Dai,

“The river has a soul—

it knows, stretching past the town,

from the first drop of rain to dry earth

and mist on the mountain tops

the river knows

the immortality of water.

A shrine of happy pictures “

…………

The river knows, what most of us have forgotten, the immortality of water, that the river is sacred. The river is a life giver, and treats all life around her equally, within the Map and outside. She minds the life around her, not selected human beings.

Which is not what we see among human beings, those who think they are more equal than others, hence have more rights. That is what Sanjukta Dasgupta is asking herself, and asking all of us, when she wrote about the Lockdown in March 2020, locking down thousands of innocent helpless people, within the map, but still outside their own map. Many died on the way, as there were no refugee camps. It was all because a few wanted to keep their areas of the map safe from the pandemic.

“M’Lord

Are we Citizens

Or are we refugees

In our own country?”

This poem is valid for all living creatures, who are refugees, if not their entire lives, but even at times. Because most of us are refugees, in our own country, always.

The river is Feminine. And she has been abused, disgraced, molested by man. Then, we find many poems have been written about the female of the species, who are the most suppressed and oppressed creatures on earth, even among the suppressed and oppressed societies.

Nabina Das takes up their cry, urging Anima to awaken Tejomila, a symbol of suffering, even the people of Assam have almost forgotten.

“Now is the hour for Tejimola. She is back from the dead.

From the many deaths. From the blood in the pumpkin

vine, from the splintered limbs in the rice pestle, from the

torn ligaments tangled in the branches of the trees. ……I, Anima, can feel Tejimola waking up inside me. Across

acid fields, shanties, human dumps, torn dreams, electric

wastes, I walk on. If you hear someone saying life in a

sunrise voice, you must know it is us. Two women gone to

three and four and more. We’re waking up to take on the

tangle and the tide.”

Then we meet Robin S. Ngangom talking about the other Easter.

The streets are only half-emptied,

not everyone has gone to witness

the resurrection of the son of god.

On Maundy Thursday no one washes

the feet of the poor

as the son of man washes

the feet of his automobile.

Under Easter stars

listen to the haunted organ

lifting a ghostly hymn, and pray

with a paschal candle in your heart

for the sorrow of the woman

shut out from a church.

When we are Mapping the Mind in order to Mind the Map, one of the most urgent, critical issues always would be concern for our environment, to preserve our ecosystem. If we destroy it we are destroying ourselves and there would not be anyone left to mind the map. That is probably why Sengupta decided to select this poem about the Chipco movement, already forgotten by many. In her own words, “* Chipko movement, also called Chipko andolan, was a nonviolent social and ecological movement by rural villagers, particularly women, in India in the 1970s, aimed at protecting trees and forests slated for government-backed logging. (Location: Bhagirathi River valley, Himalayas, Uttar Pradesh.)

Sanjukta Sengupta wrote,

“As women hugged the trees like mothers

No word or force could

Tear them away

From their beloved trees.”

Women have always been with nature, with all life around us. She was always aware that trees have their own life, that they create life, and support all life. Women also know that trees are as sensitive as all humans, that they feel pain, they feel empathy, that they communicate with each other.

Talking about our ecosystem and humanity, is Smita Agarwal, in her poem, Earth Day,

“Oxygen has been convinced it’s Carbon monoxide.

It must exit the planet.

Finally women are being conditioned to say,

“We love to be groped and raped”.

And Love, that smart aleck, is on his way

To a newly discovered galaxy which supports life.

He’ll settle down there, self fertilize,

produce yet another army

of callous progeny”

Tabish Khair, dares to write,

“Barbie

The girls who skipped and laughed, collecting dung,

The boys who shrieked in mud between errands,

She now knows in some minds across the land

They have no navel, they have no tongue.”

Khair also points out,

“Things contain in themselves so many things,

You can never just name them like Adam.

They are themselves and always something else.

I wish you would understand this

When you look at people and see an alien,

And say refugee, unbeliever, Muslim, gay.

With them, and with stones, trees, birds,

How everything impersonates something else.

There is nothing that is itself alone.”

There is nothing and no one that is itself alone. We are all one, one living entity, on a planet, in a universe that is alive. Unfortunately we have forgotten this universal truth.

Usha Akella, in her poem, “The repetition of it in Sri Lanka, and elsewhere”, she ends it with the lines,

“And whatever color I wear or whatever prayer I say,

Whomever I love or lie with,

there’s always ‘the other’ who will torch me till I am bone.

I join the living dead, a stone.”

A writer identified as a Diaspora, after writing about the tragedy of mankind around many locations identified in different maps, she ends up with Sri Lanka, where innocent children, women and men suffered, died, and faced a 30 year conflict, because each was made to look at ‘the other’ with suspicion and hatred.

I see in her poems the pain of all the suppressed and oppressed people ‘other’ around the world.

A rare diaspora writer who really feels for her motherland and her people, including the ‘other’ everywhere.

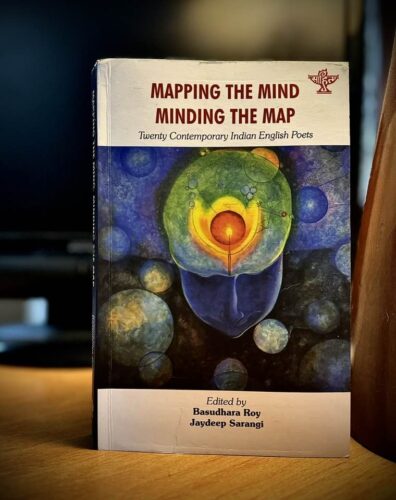

In this anthology, Mapping the Mind or Minding the Map is confined to a modern geographical and political map, while the borders have been shifting regularly. I am reading this anthology from outside the present map. I have personally met only two of the twenty poets collected here, but have read poems of several others, as a neighbour who visits the mapped region regularly.

It was not easy to select a limited number of poems out of the two hundred published, and my selection to discuss is not representative, but only the ones that caught my mind, as a reader not totally familiar with the varied culture, mythology and society contained within this huge land mass within the map.

These are also poems written only in English, while there are an immense number of poems written in the 22 scheduled languages, 122 major languages and over 1600 other languages, within the map covered. Poetry is in the blood of all Indians and they have been writing poetry for millennia. That is why we need translations of poetry in these languages. There was one poem by Sudeep Sen, which I kept to the last to comment. He begins with a quote from Calvino.

“LANGUAGE

Without translation, I would be limited to

the borders of my own country. The translator is

my most important ally.

—Italo Calvino

My typewriter is multilingual,

its keys mysteriously calibrating

my bipolar, forked tongue.

Black-red silk ribbon spools, unwind

as the carriage moves right to left.

In cursive hand, I write from left to right.

My tongue was born promiscuous—

speaking in many languages.

My heart spoke another, my head

yet another—the translation, seamless.”

Without translations, even within the region mapped out by the editors, no one would be able to read and enjoy most of the poems written, which are not written in English. Even the poems written in English, only by about 6 – 10 % of the total population.

We cannot see any solution to this problem, until and unless we could develop a universal language, or be able to use Artificial intelligence to translate any language to any other language.

*

Add comment