My great grandmother wore a white thaan — a plain sari that was the garb of widowhood — cooked in a separate kitchen and consumed only vegetarian food. Needless to say, her culinary skills yielded memorable tasty morsels for all of us as did that of my grandmother. My grandmother spent her widowhood in white saris with a narrow border, ate vegetarian but cooked non-vegetarian food for all of us. She used the normal kitchen for all cooking but would not eat any eggs, fish, meat, onion, ginger or garlic. We all tried persuading her to eat everything. Didn’t work. Luckily for me, my mother-in-law, who I met as a widow, wore normal clothes and ate normally like the rest of us…

Each generation in our families saw widows integrate into the normal sphere as grieving individuals. When my father became a widower, he mourned his wife and joined her in the ethereal realms five years later. He was as sad as any widow would have been to lose a spouse.

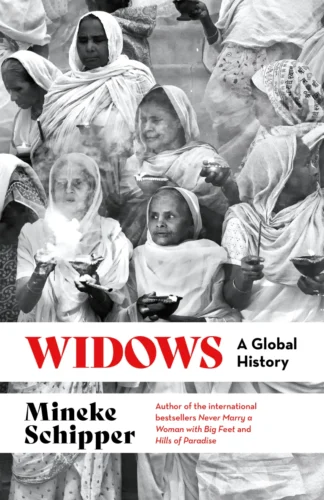

So, when I came across a book called Widows: A Global History[1] by the Dutch author, Mineke Schipper, I was curious. On the cover was a picture of widows in Varanasi. Just having worked on an anthology on violence against women, Our Stories, Our Struggle[2], I was keen to learn why we needed a separate book on just a single group of women. Was there a reason for it?

As the pages turned, horrific stories unfurled across the world… stories of killing, burning, making widows drink the water in which the dead spouses’ bodies had been washed, even familial or non-familial rape cropped up. In some cases, it was sex with a ‘cleanser’ to cleanse the dead husband’s interest in the widow. One read of how degenerate social norms could be across time and geographies. The main reason for the perpetuation of such norms was given as greed for property in the extended family or village of the dead man and patriarchal mindset, which originated with the realisation that a woman birthed a man, a unique property which made the opposite gender feel threatened. Therefore, dominance was asserted by the patriarchal system.

As education spread through the world, the communities reformed. She tells us: “The story is much the same everywhere; widows who are well educated know what rights they have or are able to find the right authorities to approach with their questions, while women with little or no education continue to suffer from malevolent practices.”

Her narrative reflects how education had changed the Western world:

“How far have things advanced for widows in the West? One major advantage for these women was that by the year 1800, large numbers of Europeans were literate…”

Our Stories, Our Struggle’s focus was on South Asia. Was this also the truth about South Asia? In the late eighteen hundreds and early nineteen hundreds, what were the stories of women in my community? That would probably have been before the time of my great grandparents… My great grandfather, a Hindu, married a Brahmo[3] woman who rode horses and spoke seven languages. When she died young, he remarried, ensured his second wife never had a baby so that she took good care of her stepsons. He died early, leaving his second wife to look after my grandfather and his younger brother. The great grandmother I knew was the second sturdy strong young bride, who never remarried and wore the white thaan till her death.

Sunil Gangopadhyay’s fictitious independent young Bindubashini[4] would have come before her times… in the 1850s. Bindu turned widow and returned to her parent’s home. As her family felt her chastity was being threatened by the love of the young protagonist, she was sent to Varanasi, where she lived as a chaste widow, till she was abducted and forced into prostitution by a goon. As a result, her father declared her dead to the family, even before she jumped into the swirling river and ended her life. She did lose her chastity as a widow, but in Varanasi, in the terrible hands of strangers who raped her into submitting to prostitution. A remarriage would have been unacceptable. Though the widow remarriage law was passed in 1856, it is still not socially accepted in all communities. In any case, a widow should be given the freedom to make her life’s choices over her marital status.

Why should a woman have to necessarily depend on a man? Or why should she be ostracised if she loses her spouse as in the case of widows living in Vrindavan?

In her book, Schipper has dwelt on ‘witch villages’ of Africa, basically support communities for abandoned widows, and on the state of widows of Benaras. She has also written of sati — another issue that has been in the news since the people convicted for Roop Kanwar’s sati [5] have been freed in October 2024 due to ‘lack of evidence’[6]. Despite more stringent rulings post her sati,[7] women continue to be burnt or self-immolate[8] at their husband’s pyre. Even if it’s a few cases, is that acceptable? I do not want to dwell on the sati cases, but can people who abet self-immolation be regarded as sane or civilised? While we wiped out cannibalism and it is viewed as a crime and disgusting, burning a young girl or an old woman on the pyre of a dead man is not?

As of 2020, there were still 250 sati temples in India[9], including one dedicated to Roop Kanwar. If such deaths are glorified, can we call ourselves civilised? Roop Kanwar was educated. She could read and write and wanted to have her own beauty salon. And yet she burnt at her husband’s pyre. I was not witness to the atrocity but, in 1987, when the incident took place, I had just stepped into my twenties — Roop Kanwar was a year younger to me — and at that point, I could not imagine being married. I was studying and had a career to dream of. Yet Kanwar lived about only 500 kms away from where I was. She could read and write. By Schipper’s logic, she, a literate, should have resisted sati as should have the rest of her family, knowing it was as illegal as cannibalism, murder or rape. But did that happen?

What is the difference between the education that wipes out diseases from a society and helps it heal from social ills and just literacy that allows one to read and write? I am not an activist, but I know freeing these convicts on the grounds of lack of evidence is unacceptable as are criminals who continue to walk free with disappearing or altered evidence. Living in a world that has given me an education not to accept social ills and rituals that threaten human lives, I am at a loss to understand or comprehend why society distorts/ condones crime, murder or any form of violence, giving them coatings of rituals, caste, creed, corruption and politics.

Widows, an eye opener, left lingering thoughts… in South Asia, can education be more than literacy for those who stay entrenched in dark rituals that destroy human lives and constructs? Will such a possibility be as nebulous as world leaders agreeing to pacifism and stopping wars that in the name of defending modern rituals kill and destroy? How long will we conceal heinous acts in the name of manmade constructs?

[1] Widows: A Global History by Mineke Schipper, Speaking Tiger Books, 2024

[2] Our Stories, Our Struggle: Violence and the Lives of Women – Narratives and Poetry by South Asian Women edited by Mitali Chakravarty and Ratnottama Sengupta, published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2024

[3] Brahmo was a cross between Hinduism and Christianity, a monotheistic religion founded by Raja Ram Mohun Roy (1772-1833) and further popularised by the Tagore family.

[4] Shei Somoy (serialized in Desh Patrika, won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1985) or Those Days (translated by Aruna Chakravarti)

[5] https://theprint.in/ground-reports/sati-economy-still-roars-in-rajasthan-youtube-as-jaipur-court-closes-roop-kanwar-case/2331357/

[6] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn8ykmn2p1go

[7] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237707719_Sati_Tradition_-_Widow_Burning_In_India_A_Socio-Legal_Examination

[8] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/law-and-history-review/article/policing-sati-law-order-and-spectacle-in-postcolonial-india/BC5AB8CE00A4F2BB630C0294F0A2DB70

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)#:~:text=The%20modern%20laws%20have%20proved,to%20the%20practice%20of%20a

Add comment