When you meet Jayant Kaikini, you are already thinking of many of his short stories and the people who inhabit his story-world(s). His Bombay. Its mannerly crowds. The autorickshaw fellow who never shortchanges you ‘even in the middle of the night.’ And many such things.

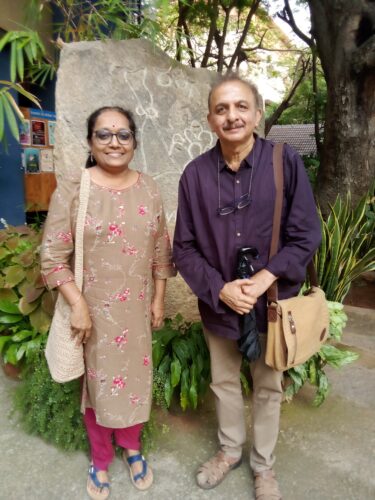

I had five questions that I ran past my editor to ask him. The questions were shared with Kaikini and the plan was to talk about literature, his writings in Kannada in Bombay and his Bombay in Kannada, etc. Our phone conversations were anticipatory of these addressings. We thought we would meet when convenient for both, and it finally happened at Ranga Shankara in Bangalore, in the good old summer month of May.

As was wont, I did not stick to my questions. They were there in the background for our conversation to wheel freely.

Not unpredictably, somehow, we started off with Bombay.

“What Bombay did to me was: it turned me inside out, like a tea shirt that you dry out, with the inside out. My inhibitions and complexes were all exposed in Bombay.

At home we spoke Konkani, I mean, you do, if you come from the region that I came from; one learns Kannada in school– reading and writing. Strangely, girls those days were taught Marathi as well, as our region was part of the erstwhile Bombay Presidency, and the marriage market was across the border too– girls would likely fit better in a Marathi-speaking family with such additional skills. Sort of. That was not the case with boys. So, you have a very vibrant language-culture in the region. Even if you are shy and self-doubting as I was, you are already familiar with two to three languages in a single setting, in the company of your elders at home, with sisters and young women of the family in their circles, and with friends on the outside. You are adept at understanding your own culture in a nuanced way. The most traumatic experience for me, however, was when I moved away from Gokarna to Kumata for graduation, and later to Dharwad for my Masters in biochemistry, from this Kannada medium to where English was spoken. For a good time, I had been quite traumatized. I am yet to recover from that fear (chuckles). I get these nightmares, ‘oh god, there is an exam tomorrow, how am I going to manage?’ Such inhibitions and personal doubts were fully exposed when I landed in Bombay. I was like a tea shirt dried out with the insides of me facing the world.”

The childhood household had always been agog with literary and social activity. Jayant’s father, Gourish Kaikini, himself a teacher, journalist and eminent litterateur, a friend of many progressive writers, always had poets and authors visiting him at the household. “I was the one who counted the heads for tea. One of the most vivid memories was the sight of those empty teacups that lay next to the chairs that people had either vacated just then or were about to occupy, waiting to be served tea. You again prepare tea. I never thought of becoming a writer witnessing all this literary activity at home. In fact, I didn’t want to. But again, I had begun to write and that stayed on. I don’t think I wrote a lot, probably have written for a long period of time. Like, two pieces a year? So, it’s only later that one saw these writings in the form of a collection– you can say, a collection, maybe once in five or six years?”

No Presents Please introduces us to Jayant Kaikini’s fabulous world. Translated into English from Kannada by Tejaswini Niranjana, it is a collection of short stories that echoes the sonorous internal navigations of people that are connected externally to the sounds and smells of the various tracks of Bombay. “It is a city that respects your hard work, your labour. Everybody knows that the other person is there for a livelihood. Everyone’s earnings are precious to the other person. No assumptions there. In the middle of the night, a rickshaw driver would tender you the exact change for a note that you gave him because he knew that your money was valuable to you.”

Mumbai as a city had taken Jayant Kaikini to a new milieu from his own, but it did keep him close to his language. “Can you believe that there were a good number of Kannada medium schools in Mumbai at the time? They were run by devoted Kannada sanghas, individuals in them, doing their daytime jobs and running these classes in the evening. Never for any profit. It was such selfless service to their language. It was here that I found my friends and my supporters. In a way, it really helped me, being away from the Kannada literary circles … and being in a new place where you had these cultural and linguistic bonds to move independently in a new setting. I would write from Mumbai, and sometimes it felt as if I was cut off from the literary issues of my home region, but I was able to find new subjects, new people, new ways of understanding life.”

“I personally was never close to the processes of how awards or literary events were won or devised or validated. As I said, my being away had changed many things for me. I was very much part of the Kannada literary, cultural scene but was also away from it, and into many more languages and cultures at the experience level. For example, when I was in Hyderabad working for ETV Kannada, I did a series of television programmes/talks on Kuvempu, Shivram Karanth, Bendre and Raj Kumar and it was done with great love and affection for the literary traditions of Kannada. I received fabulous response. But then I was also interested in life around me, at that time Hyderabad, later in Bangalore. From Charminar to humble hawkers.”

Jayant’s fondness for the form of short story is formidable. There is a lambent quality to his stories, in a way congruous to the world of his characters, sometimes the fringes of their life, and oftentimes to the connections that individuals build with a city, and within a city. The response of a character to small spaces/ large rail lines and the bus stations brings out not only the reconciliations of the human mind with self, but also the discontent and dystopia that his characters encounter in the external world. Jayant imaginatively retrieves this world and recreates it in matchless detail. “You know, some of these characters happen to you. You meet them – for example, a shy, reticent woman of marriageable age whom the protagonist does not meet but is caught in a match-making effort of her brother (although it doesn’t go far); it is an experience in which you notice our fragility, our compassionate spirit, and you realise that you are no longer looking at the city, but trying to understand the person through the city, or with the city because you are a part of it.”

“There used to be this relative, who used to come from Bombay to visit us in my younger days. His promise always used to be that he would bring me a pair of shoes. This is like the highest form of a promise. Shoes from Bombay! Every time he visited us, he would measure the size of the foot by drawing it on paper with a pencil. He never brought me any pair of shoes, but on each occasion, would measure my foot. The line would change in length, but you never got them from him! The world outside doesn’t simply exist on its own. It exists because of us. The frailties you notice, and the love you develop with people.

I met my future wife at workplace. I was a chemist at a prestigious balm-making company in Bombay and she used to be the quality-certifying officer. Unless she approved, my chemical compound wouldn’t pass (chuckles). So, our bond seemed to have had some real chemistry to it! And it is these connections that shaped my world.”

As one of the pre-eminent writers in Kannada, Jayant Kaikini’s work celebrates an unusual autonomy: of thought and deed. That’s what sets him apart from the others perhaps. He has not only moved between cities, and the relocation-swathes of internal turmoil, but also between different professions, different demands of creative and chemical crafts. He has been a biochemist, a creative content writer, content-maker and presenter within the television and advertisement circuits, lyricist, and a freelance writer. “I hope I can someday retrieve and digitalise those features on Kuvempu and others,” he says, stoked by a key memory. It’s as if he had suddenly realized to put salt in a gourmet dish of delicious memories of a significant literary career of observations.

His most recent busy engagement has been with Mani Ratnam on the film, Ponniyan Selvan. In writing the song lyrics for the Kannada version. “I wasn’t keen on transliterating the Tamil lyrics. I communicated the same to him. It was wonderful that he gave me complete autonomy to write the way I saw fit. Most of the songs in the film came in the ‘background,’ and lip-synch was manageable. Writing for Ponniyan Selvan’s Kannada version—its songs—has been such a great and wonderful experience for me.”

Kaikini’s geniality illuminates his experiences with the celluloid industry: “when I visited a super star for the first time for a story discussion, years ago—he was already a super star— I was quite nervous, but he was very approachable, humble, and supportive. I sat with him, quite excitedly, for a story discussion in his house, at the dining table. The table was uneven and would gently shake every now and then. And here I was, thinking, “what a relief, even in a super star’s house, the dining table can be imperfect.”

***

The questions that were never asked in the way they were written down:

Question 1: Is the city an inspiration for stories? Does a story change with the change of its location?

Question 2: Is it important for you to ‘plot out’ what happens in a story? Or would you rather that the character (a human experience) be known through your story? How do you negotiate the two?

Question 3: Do you think that the state has any role in the recognition of a writer? Is there a way a writer controls it, in your opinion?

Question 4: How do you deal with “the changing times” as a concept while engaging with creative writing?

Question 5: How close are you to the Kannada literature in assessing its association or its contrasting position to any other literature in India? How do you keep up with the trends in other forms of literature– Also, in other languages?

[1] A familiar introduction to the beauty of Kannada comes from the words of Vijayanagara emperor Sri Krishnadevaraya’s ready reckonings in Telugu, his poetry, and his eulogization of the Kannada language as kasturi: aromatic and mesmerizing. I am consciously invoking that memory of a definition here.

Add comment