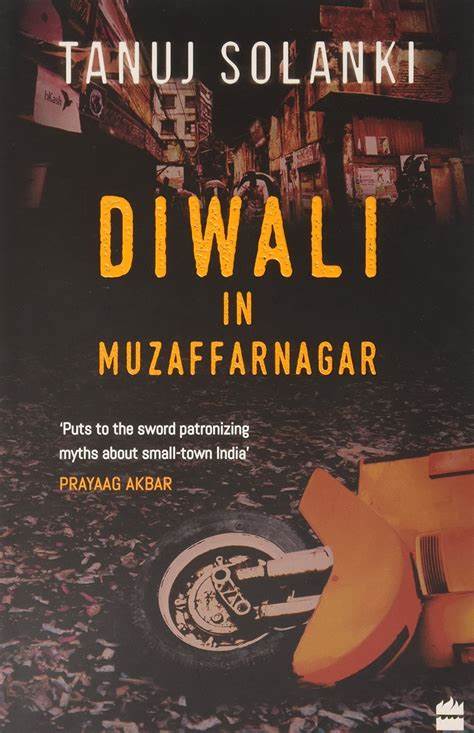

Tanuj Solanki’s second book is a collection of eight short stories related to a town that’s “peaceful except when it bared its ugly side”. The book recently won the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar Award in English (2019).

“This town is shit, she thought, and smiled”- this being the last sentence of the last story in the book, titled “Compassionate Grounds”. The choice of it being the last story is apt, and that last line even more so, as we shall see in the passages that follow.

The collection begins with the one of the shorter stories in the book, “The Sad Unknowability of Dilip Singh”, where the protagonist is a tormented, struggling poet trying to move his craft into prose poetry and in the later days, into short-stories. To lazily summarize it, it’s a story about a failing writer who ends his life-not an original trope in fiction, and stands at the risk of over-romanticizing the travails of artists that’s been done innumerable times in cinema and literature. But, just in these six pages, Solanki has probed details and textures, and tried creating a portrait of “unknowability” that ricochets between the writer and the writing. Let’s begin at at the beginning: the suicide, when the mother finds Dilip Singh hanging from the ceiling fan, her “plain widow’s sari” around his neck. Let us pause for a second, just consider the irony in this description- and what it says about the use of Solanki’s props in pushing his narrative (nylon string/coir/belt…all might have done the job, but the widow’s sari is an embodiment, almost its own character- and these props, as we shall see, will recur throughout the collection).

Let’s now talk about the transition of Dilip Singh—and right before we go to the disconnect his friends felt about his poems, to the improvement we are shown through a line being re-written, the narrator admits that the label of a “writer” is a problematic one, even for someone who has perhaps authored several pieces, “none of which were published”. In Singh, we are given a writer whose voice changes, over the years, from phony to real, more nuanced. So “the grey sky gave out a grey piss” moves from the surface to the interior, becoming, in its final draft : “Everything was the colour of my mind”. Here, we approach a more knowable Singh, less obnoxious, and more confident about his influences. This leads the narrator, who regularly meets him at a sea front, to the assumption that he was happier. Now there is a connection right to the first passage, where we are given the source of the mother’s widowhood: Singh’s father’s death. Again, the cruel irony of spaces and objects, the image of Singh standing next to his father’s corpse right where he would eventually end his life. What does this tell us about Solanki’s craft? Sure, it’s a calculated, clever move, but it works, and employs space as a chronicler of grief. And from grief, there is the Singh whose now-authentic voice, claims to have landed him a poem acceptance with a reputable publication, though the poem, to reinforce the unknowability, is never published.

“My Friend Daanish” is one of Solanki’s most accomplished stories, and also features a character, Gunjan, who returns in the last story, “Compassionate Grounds”, as an adult. And the story introduces an important prop, the Honda Activa, which is centered around the title story, “Diwali in Muzaffarnagar”. The story is in an adolescent setting, where Tarun is a meritorious student who has been gifted a scooter for topping his eleventh class. The gift is an encouragement from his parents to motivate him to excel in what is, in India, the most important school year which plays a crucial role in the admission process to professional colleges. The twist in the tale is that, the placid, unintrusive Activa befriends a rebellious Bullet, a bike known for its machoism and roar, in the guise of a maverick named Daanish— and Tarun’s affinity with Daanish is because “he is someone I couldn’t be”. Stories of boyhood heroes and their adventures are again not new to literature—but here, in Muzaffarnagar, there is always, in the author’s narration, the sinister undercurrent that friendship is priced with a local flavor.

So it is in this story, that Solanki first explores the socio-politics governing the mundane in Muzaffarnagar. From bunking classes, to initiating Tarun to eating chicken, to his dexterity with automobiles and short-cuts, Tarun, in Daanish’s company, learns that “there are other kinds of valuable knowledge in the world”. Through these internal conversations mixed with gestures that seem fascinating to the youth, Solanki manages to invest us in this growing friendship between the two students. But the underlining difference here, and one that is crucial to the storyline, is not of personality, but identity: between Hindu and Muslim, in a town fraught with communal tensions. And it’s in the fleeting, loaded interactions and ceremonies—the only rule during prayers was to join our hands; some made a fist of one hand and covered it with other, some joined open palms, some interlaced their fingers—, and when Daanish turns up at Tarun’s house unannounced—She then asked him for his name and on hearing it, turned to look at me with an

awkward smile. Returning to the vehicles, they are also literary vehicles that propel the story towards the cultural, where the streets become interrogators and the dust clouds the wheels throw-up are miasmas of prejudice: Soojdo Choongi, a muslim majority village that wasn’t deemed friendly.

Another detail Solanki frequently utilizes to lend believability to the narrative, is money. “Nine hundred rupees of extra pocket money; it could have been eight hundred rupees, but I couldn’t lie completely”. In fact, the relationship between familial relations and monetary circumstances bolster the later stories, “Good People” and Compassionate Grounds”. And again, when Tarun confesses to Daanish that he doesn’t have enough: “Did I say anything about money?”

My Friend Daanish ends with the chilling conclusion of “celebrating a day that generally had no business being celebrated in Muzaffarnagar”. In this story, Solanki’s descriptions of student life, communal relations, conservative locales, domestic upbringing and adolescent desire, all work together, gathering momentum to seal the suspense in a revelation which—enabled by technology— might be called, sanitized tragedy.

Now the title story, Diwali in Muzaffarnagar, features an adult Tarun who learns, on the most festive/auspicious day in India, that his brother, Kanu, has met with an accident. All Indian roads are infamous for these types of accidents that result in ugly altercations, and where the sucker ends up paying for the damages. Now Solanki, by using this seemingly quasi-humorous, commonplace incident, overturns the normalcy by employing, what on the surface seems to be familiar dialogue: “What happened?- I had an accident. A little one” “On the day of Diwali, I thought” —and lines like these, that shift the story into the character’s interior to reveal moods/epiphanies/secrets to the reader, are probably Solanki’s most significant accomplishment in terms of craft. So using a straightforward plot, we are given an insight into the dilemmas of a day in Muzaffarnagar, albeit an auspicious one. And as the story progresses, the author begins dimming Diwali’s festive lights until there is total darkness. Again, Solanki’s detail in monetary transactions, where Tarun’s father is trying to negotiate with the other party (the saving grace of them being Hindus too) involved in the accident; but he’s quickly cut-off by a reasoning that’s problematic to mitigate: ‘Bhaisaab, it is Diwali Time’, the man said. ‘My festival has been ruined.’ Also, the predicament is accentuated by the fact all this is taking place near Soojdo Choongi (a muslim majority village that wasn’t deemed friendly), and there’s a desperation to conclude the unsavory business as swiftly as possible: “panic and prejudice make one do things”.

In Solanki’s stories, the tone often metamorphoses in the characters who span different generations. The ninety-four year ailing grandfather in the title story for instance, and the cruel honesty in admitting the burden of his existence to the entire family: “And this old man doesn’t die. Hangs on and hangs on and hangs on. I want this man to die.” . And the fleeting comic interludes of this nuisance of a man, when the house is still plunged in the aftershock of the accident: “Congress is screwing this country”. The point of delving into all this is to underline the dexterity of Solanki to narrate a story that’s relatable and ambitious—the shift in perspectives, the internal monologues, the helplessness/anger/defeat, longing and sexuality, the situational architecture opening windows into invisible realities unique to Muzaffarnagar, and still poignantly steering these ships to their harbors. Like the window creating an awareness of the geography—so the phone as a prop: one that interrupts Tarun at the beginning of the story, as he’s trying to climax to the memory of Marie-Anne, and later, post-accident, amidst the emotional turmoil in the house, a phone-call from Switzerland that re-establishes the link, and then the eavesdroppers who pursue the symbolic significance of this call till the familiar talk of marriage and caste—a revelation about Kanu’s sexuality—and in all this, the most jubilant member of the family is the old man everyone wants dead. The question any astute reader might ask here is if Solanki is packing in more detail than warranted? Has he over-labored to establish these connections in the story: contrast an ugly-Indian town with the gorgeous Interlaken, or revealed the sexuality of Kanu to forcefully add an element of surprise—how would the story have worked if Kanu’s relationship with Arun wasn’t revealed? Or Tarun’s decision to cut ties with Marie-Anne? Why must all this be happening on this hellish-Diwali night in Muzaffarnagar?

My favorite story in Diwali in Muzaffarnagar, is Good People. It’s about a newly married couple, and the wife, Taruna, is a survivor of child-sexual abuse. Solanki is timing it, giving us the mildly-interesting post-marital bliss scenario, honeymooning near Lonavala, there is cuteness… there is sunshine under the lines…levity…the sensual, until the question is popped, just-like-that: not the who, but the what.

The proverbial piano is at play here: pushing the right buttons at the right time, and Solanki’s metronome is guiding his fingers as they tap out the story on the keyboard.

The memory, the things that lead back to the memory: grubby fingers, tobacco drool, kurta-pajamas with the top button open…the net of associations leading up to her marriage, to discover in her husband “a good man, a man who could be pained by her pain”.

But before Lonavala, the honeymoon destination was Iceland. To illustrate this seriousness, Solanki even slips in the husband Ankush’s reading-list comprising Icelandic murder mysteries (perhaps a trivial detail, but is it alluding to nature of the story being written?). But then—again reiterating how the author’s monetary considerations of his characters root them in believability, this dream of the aurora-borealis in an exotic locale is punctured by their financial circumstance. The bride’s father who has—in a typical Indian tradition— spent a fortune on her daughter’s marriage. And Ankush, who began to see the expensive as unnecessary.

Whether Solanki is writing a chronological narrative, or delving in flash-back, there is, in the dialogue, an element that links to the core of the story: like in the case of Ankush’s first meeting with Taruna, where the talk was about child sexual abuse. The narrative moves into their courtship, the logistical difficulties of working in different cities, till the deal is almost sealed, and in a meeting with Ankush in a café, by telling Ankush, the reader is let in on the fact that Taruna’s abuser is actually someone related to her. This decision to place the Who after the What is a testament to Solanki’s ability at positioning suspense. But there is something strange here, not the clear-soup they’re having but a challenge that is of a species different, more noxious from the challenges that usually accompany marriages.

The figure of the moribund, burdensome man, returns in Good People, but this avatar, though even closer to death, is just more menacing, and a severe moral quandary that strains not just the wedding, but the newly-weds and their spaces, forcing them to re-examine the most basic ideas about the ends to which money is a means, and looming large and stubbornly over the atmosphere of what should be a festive, cheery home. Solanki is a cruel wordsmith in deciding to keep this tormentor alive as long as he does, and it’s perhaps not entirely foolish to speculate about the toll it must have taken on him to create a situation where the humane- the morbid- the financial- and the bottomless trauma of the survivor all function together to blot out the sunshine he initially gives us in the beginning passages.

In Diwali in Muzaffarnagar, the reader has a literary ticket to the confounding, the traumatic, the absurd and the living-ghost, to heroes like the adolescent Daanish and the elder Gunjan, to Taruna and Ankush who, in a fiction of my own making, hope make it to Iceland. And also, to return to were we began, the unknowability of a writer whose affinity for the sea-front couldn’t save him from dying in Muzaffarnagar.

*

Add comment