I first chanced upon a Marathi fictionalized memoir written by my great grandfather at the British Library in London, in 2014. This memoir, based on family history, was written in 1895 and described my great grandfather’s father’s (my great-great-grandfather’s) conversion to Christianity in April 1840. The book had even won a prize in 1895 from the Bombay Tracts and Books Society. I was fascinated with the story, and later translated the memoir into English, and edited, and introduced it for re-publication. The book was accepted by the AAR ‘Religion in Translation’ series after rigorous review and published by Oxford University Press in 2019. The writing and translation had me in a state great excitement, reconnecting me as it did, to family (and doing family-history as a method) in unexpected ways.

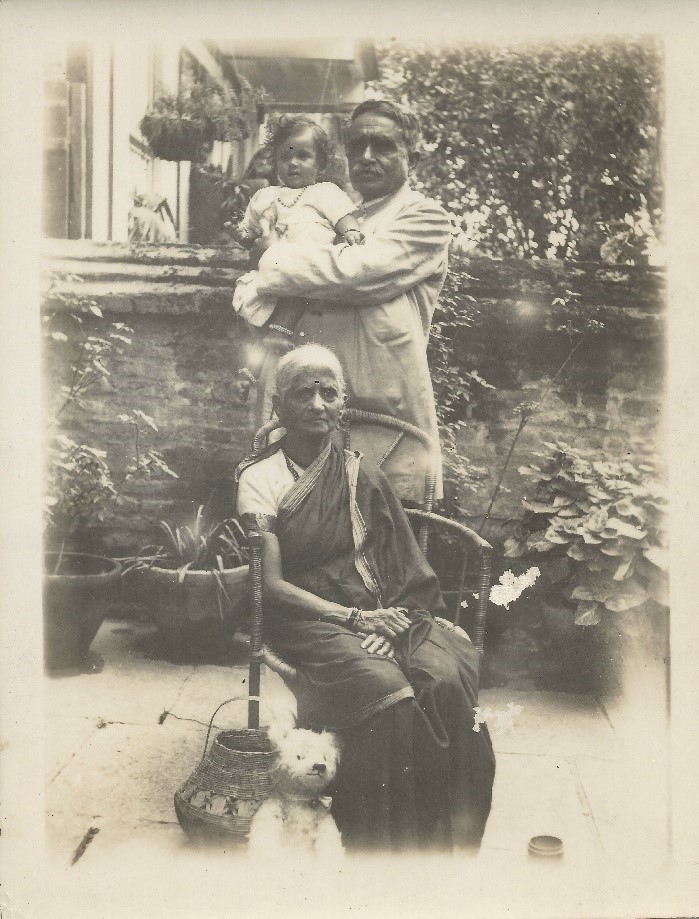

My great grandfather (the author of the memoir) was born at the small mission-cantonment town of Malegaon in Maharashtra (Bombay Presidency), about a hundred kilometres north of Nasik. His father, my great-great grandfather (the convert) hailed from a Chitpavan Brahmin family that had moved to Panchavati—an impoverished place unlike today—on the other side of the Godavari River from Nasik, after serving the Peshwai till 1818—the last post abdicated, being the Subhedari of Chakan. The family underwent impoverishment after the fall of the Peshwai, and the road ahead suddenly looked untenable and bleak.

My great-great grandfather, a young boy at the time, had grown interested in English, and had wanted to study at the newly established missionary school in Nasik (at Sharanpur) in the early 1830s. He was disallowed from doing so, because the family had to maintain its pride as Brahmins, and its status as supporters of the defeated Peshwai. Orphaned at an early age, with a brother far older to him, who was anxious with managing their financial affairs in a way that would keep family pride and status intact, my great-great grandfather was mostly left alone. He gradually became attracted to Christianity, making friends with boys who were already studying at the mission and had converted. Encouraged by them, he spent his time secretly reading Christian texts, and the Marathi Bible.

Finally, he made up his mind to convert, and accompanied by his much younger wife in April 1840, left home for the chapel of Church Mission Society (CMS) in Sharanpur to accept Baptism. The couple never returned home, though they continued to live in nearby towns, as if existing in a parallel universe. It felt lonely to read about their life, and yet, tremendously courageous. After conversion my great-great grandfather struggled with his sudden redefinition as an individual, who was solely responsible for himself, his wife, and children, without access to family support or resources. At a relatively older stage, for he was already in his 30s, he began re-educating himself painstakingly, and gained a profession that would sustain him and his immediate family.

His Hindu-Brahmin family, not taking his conversion lightly, first tried to poison him. Failing to kill him, his older brother tried to commit suicide. This caused great bitterness for the family, and my great-great grandfather wrote later of the madness of the 1857 riots. European missionaries had fled the missions, hearing rumours of riots organized on Muharram day in August 1857. Many converts like my great-great grandparents were left to man the mission premises, at the receiving end of rioters that ransacked, destroyed, looted, and killed. My great-great grandmother had, moreover, just given birth to their first baby some months earlier in 1857. The couple suddenly faced mobs at their doorstep in Junnar. They went into hiding, barricading the gates and walls of the mission buildings, that were promptly burned. The couple finally took shelter in an abandoned warehouse, remaining as silent as possible for the next four days. The heat, damp, and stench of smoke was so formidable that my great-great grandfather, being an asthmatic, developed a nagging cough that troubled him for many years. He described how the couple’s continuously prayed at the time, asking God, whether this was the end, and whether they had been redeemed and kept alive only to be brutally chopped to death! They survived the rioters who never thought of looking inside an abandoned warehouse.

Apart from such dangers, my great-great grandfather had a happy, and successful life as a native pastor. He was active in the regions surrounding Nasik, where he proselytized among Adivasis. He spoke two different dialects of the Bhil language quite fluently, and composed numerous hymns in these languages. He spent many years in the Anjaneri region of Nasik, and being musically talented, also played many Adivasi instruments. His wife was lauded by CMS missionaries for her leadership in serving the native Christian community, and for fostering many Adivasi children. Some of the children she fostered came from African backgrounds, rescued by CMS missionaries in Bombay from ships captured in the Arabian Sea.

Later as his asthma worsened, itinerating among the Adivasis grew difficult. My great-great grandfather then served as Marathi teacher, and helped out as a priest at the local cantonment hospital in Malegaon. This hospital had earlier functioned as a Lock-hospital for STDs in the cantonment area, but soon, after Lock-hospitals were abolished due to the enactment of the communicable diseases law, the Lock-hospital was turned into an ordinary cantonment hospital that was entrusted to the CMS mission.

The book’s writing brought me renewed experiences of what were old and unknown associations. I felt hope as I discovered and visited the St. Pauls Church at Malegaon, where my great-great grandfather had served as native pastor of the Marathi Church for 26 years before passing away in 1884. Helped by Church community members, it was a poignant moment for me to discover his grave, where he was buried jointly with his wife, who had also passed away, quite prematurely, in the same year of his death, just a few months later.

To complete my book, I visited many libraries and archives in England that housed the 19th century CMS records for mission outposts in India, especially Bombay Presidency. I searched endlessly for Sharanpur, Junnar, and Malegaon records. I remember one archival visit to Birmingham in particular, that houses the largest collection of CMS records. This was the first time I encountered annual reports, and letters, personally penned and signed by my great-great grandfather. It moved me to tears, to touch his handwriting. Since his wife had been a very young girl of five or six, when they had arrived at the mission, she had to initial spend the first decade at the mission orphanage and gain education at the school, before she could accept Baptism, and begin living with my great-grandfather as his wife. The school report moreover said that she excelled in English and arithmetic. The European missionaries at the CMS remarried my great-great grandparents at the Sharanpur Church, and it made me laugh to discover their marriage bans, and wedding registration details from 1851.

I grew a lot through the writing process of this book. There was excitement, sadness, and wonder. There was also a new beginning. Not only was I encountering my ancestors; I was also discovering the rich history and tapestry of the Indian Protestant Christian community and their narratives in Maharashtra that had once been part of society in Bombay Presidency, but whose memories and contributions had been erased by nationalism.

*

Fascinating archiving of personal history and recounting of your ancestry!

May I have your email? I have started reading your biography of Baba Padmanji.