I first stumbled upon the existence of Sri Lankan author Anuk Arudpragasam’s work through an interview he did with the Paris Review, published in July 2021. Among the many fascinating quotes from that interview, one in particular struck me: “It’s not that I avoid pettiness, or judge people for pettiness, but it’s something that I will not accept in a book. Maybe it has to do with coming from a context in which books are not readily available and when you see a book, you believe it’s something that has to be valued. And, therefore, if somebody’s an author, they cannot be lighthearted or flippant people, they cannot be petty. For whatever reason, the object of a book is very important to me, and for me it’s not a place to be lighthearted. I’m very impatient about any book I read or any book I write getting to the question of what life is like and not tarrying on more frivolous matters.”

An unfortunate trend of contemporary Euro-American novels is that they are often about, as Arudpragasam terms it, “pettiness”; they are about the lives of young people working in the publishing industry in major metropolitan cities like London or New York. Perhaps we can ascribe this, in part, to the professionalization of literature through MFA programs. The more offensive of these kinds of novels continually reference the ills of capitalism and racism on the page, but refuse to seriously interrogate them in the context of the novel. Arudpragasam himself is a writer working in English, and his two novels were both published originally by American publishing houses, but he absolutely refuses to suppress the lived sociopolitical realities of most human beings on Earth. Instead, in both of his novels, he looks directly at them.

Arudpragasam’s first novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage, published in 2016 by Flatiron Books, tracks the experiences of sixteen-year old protagonist Dinesh in a refugee camp over the course of a few days as he lives through the Sri Lankan civil war, and experiences his titular brief marriage to the also-teenage Ganga. Chapters of the novel are dedicated to the everyday acts of sex, sleeping, bathing, and defecating, and subsequently, the reader comes to understand the heightened importance of these acts in a violently precarious situation. Arudpragasam’s second novel, A Passage North, published by Granta in 2021, takes a step back from the visceral first-person experiences of terror and instability to enter the mind of Krishan, another young Sri Lankan Tamil man, but one who has lived his life mostly shielded from the war. Over the course of A Passage North, Krishan travels north to the site of the war to witness the funeral of his grandmother’s caretaker Rani, a woman who lost her young sons in the war and lived through it in a way that Krishan did not.

Arudpragasam’s first novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage, published in 2016 by Flatiron Books, tracks the experiences of sixteen-year old protagonist Dinesh in a refugee camp over the course of a few days as he lives through the Sri Lankan civil war, and experiences his titular brief marriage to the also-teenage Ganga. Chapters of the novel are dedicated to the everyday acts of sex, sleeping, bathing, and defecating, and subsequently, the reader comes to understand the heightened importance of these acts in a violently precarious situation. Arudpragasam’s second novel, A Passage North, published by Granta in 2021, takes a step back from the visceral first-person experiences of terror and instability to enter the mind of Krishan, another young Sri Lankan Tamil man, but one who has lived his life mostly shielded from the war. Over the course of A Passage North, Krishan travels north to the site of the war to witness the funeral of his grandmother’s caretaker Rani, a woman who lost her young sons in the war and lived through it in a way that Krishan did not.

While The Story of a Brief Marriage takes a detailed look at what it might be like to be in Ganga and Dinesh’s situation, A Passage North accomplishes the much more difficult feat of closely interrogating the issue of complicity and more generally, what it means to live in proximity to but shielded from intense violence. Most writers can research what it might be like to live as an oppressed person during a harrowing time—whether that be a gay man during the AIDS crisis in New York in the 1980s, or a black South African during apartheid—and attempt to depict these lives. However, it is much more difficult for a writer to critique both their own bourgeois position and that of the reading public. Empathy—one of the major purported benefits of novel-reading—is of course important, but the major triumph of A Passage North is in how it forces the reader to truly evaluate how they, like Krishan, might be haunted by, and even benefit from, the specter of violence that hangs over their lives.

The novel refuses to limit its scope to just Krishan’s position in comparison to Rani’s. Prior to the journey, Krishan leaves his PhD program in political science in Delhi to return to Colombo; exhausted by simply studying war and peace from a remove, he moves back home to a country that was actually affected by a conflict with tangible effects on his own life. Similarly, Krishan’s reflections on his past relationship with a woman named Anjum, an organizer and activist, weave throughout the novel, as he examines his own abilities and goals in relation to Anjum’s. Despite their ostensible political similarities, Krishan looks unsentimentally at Anjum’s true dedication to her politics in comparison to his lack of resolve. In this way, A Passage North continually moves against the grain of the curiously apolitical, defanged literature that currently permeates American markets and insists that literature, philosophy, academia, and the world of ideas more broadly must be relevant to sociopolitical realities.

This isn’t to say, however, that A Passage North criticizes the value of literature. The novel, is, in fact, shaped hugely by other texts. Arudpragasam adopts a particularly modernist style: the movement of the novel takes place more within Krishan’s mind than within a physical reality. His memories and thoughts, in turn, are not inflected by the literature of the Western canon, but rather the South Asian canon. In interviews, Arudpragasam has pointed out that even though A Passage North calls upon this South Asian canon, amplifying it to an English audience that is much more familiar with the great masterworks of the West, the South Asian canon, too, has its own violent history in which the caste system enclosed reading and writing within the domain of the elites. In the same Paris Review interview, he says, “If I was now interested in canonicity, it would have less to do with a South Asian canon than specifically a Tamil canon.” Given the oppression that Sri Lankan Tamils faced at the hands of the Sri Lankan government, and, on a larger world stage, the gradual fading of regional languages and literatures, Arudpragasam’s interest in narrowing from a South Asian lens to a Tamil one again grounds his stylistic choices in real-life power struggles. Not only must literature be relevant to sociopolitical concerns, but so must the language of this literature.

Reading both A Passage North and The Story of a Brief Marriage can feel, at times, like swallowing a bitter pill, almost unbearable, in how strongly it engenders genuine introspection. And yet, these are not novels intended for self-flagellation. A Passage North offered me, as a Telugu-speaking American, a way forward, if not a clear-clear solution. Bearing true witness—to one’s language, to one’s history, to the travails continually experienced in all echelons of society—is the first step towards change.

*

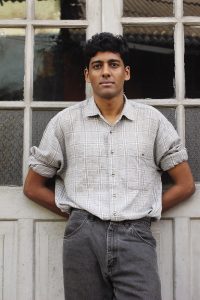

A good review of two novels and a good introduction of an young novelist Kena Chawa. The two books talks of the position of Tamils in Srilanka very welll.

Kena sums up the review “Reading both A Passage North and The Story of a Brief Marriage can feel, at times, like swallowing a bitter pill, almost unbearable, in how strongly it engenders genuine introspection. And yet, these are not novels intended for self-flagellation. A Passage North offered me, as a Telugu-speaking American, a way forward, if not a clear-clear solution. Bearing true witness—to one’s language, to one’s history, to the travails continually experienced in all echelons of society—is the first step towards change.”