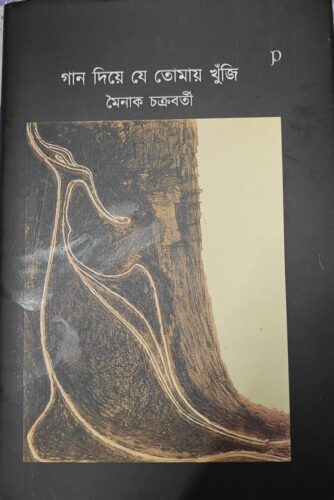

Fame and universality have its own perils. It is like Kipling’s ‘White man’s burden”. Rabindranath Tagore has either been pedestalized beyond refutation by the Bengali populace or has been experimented with obliviating his essence and contexts. The bard’s winged chariot is perennially fleeting with each passing day ever since the Copyrights have been revoked. The agency of criticism falls redundant in a scheme where the poet’s essence is rendered secondary. Amidst such an alarming scopus of critique and pseudo-theorizations, critical works like Mainak Chakrabarti’s Gaan Diye Je Tomay Khnuji stand apart as the harbinger of hope.

Works like Chakrabarti’s intelligently and passionately weave a garland tethered out of the verses of the bard himself to manifest his contemporaneity. Mainak doesn’t make any added effort to jargonize his critique with cross – references, observations or omniscient perspectives; he simply makes a bricolage out of the emanant and presents it to his readers as documented evidence of the eternity of Tagore’s relevance.

Mainak’s work is neither Rabendrik in the way of cultural mockery, not does it oversimplify or generalize perceptions to prove Tagore mainstream. He deftly uses his pen to carve out a niche territory where Tagore seamlessly acquires his deserved pedestal above the others in comparison, while also not being deracinated from his cross-cultural acceptance and universality. He collects the rubies and emeralds from created by Rabi Tagore in the colour of his consciousness, and paints with his paintbrush of perception.

Tagore’s place in a Bengali reader’s heart is resplendent with an all – encompassing glory. Mainak, with his post-structuralist anvil, hits at the base of a superstructure that tends to put an end to play of interpretations in the name of glorification of his verses. And he does so, keeping the essence, flavour and context of the songs intact.

The text, to a Tagore – lover, would soon become a gospel to explore new coigns and avenues of understanding Tagore in an unforeseen light. It enlightens the readers with known texts but unidentified subtexts. The writer seems to jostle with Tagore throughout his book urging for a shift in trajectory, to reach an end hitherto unattained. It is like a road of Ben Okri, famished after being savoured and yet unquenched. Tagore is a perennial locus of life and philosophy; and Mainak, with his deft scalpel, uses his surgical precision to decode and re-present them.

The writing style of this book is very contemporary, relatable, interspersed with intertextual references recontextualized to achieve its end. The author clearly maintains his critical distancing while offering his homage to his prodigy. His rendition is never lost in the quagmire of absolute surrender, inspiration is never overridden by plagiarized imbibition.

The musical rhapsody of Dr. Tanya Das reverberates through the narratives, the skeleton echoes with the remnants of the ending notes. The minimalist, yet befitting sketches of Ankita Sanyal not only complement the text but is also reminiscent of Tagore’s carelessly scribbled pen-pictures in his manuscripts. Mainak leaves no stone unturned to create a Tagorean vista with an edge of contemporaneity. Mainak is almost Keatsean in his endeavour, envisaging through the tapestries of romanticism like a Prophet, accompanying his readers in this sojourn to relocate and realize the zest of Tagore.

The Opening quote of this book that Mainak borrows from Tagore strikes the keynote of the text. The lines Mahabishye Mahakashe Mahakalo Majhe/Aami manobo Ekaki Bhromi Bishwoye rightly highlights his never – ending awe as he limitlessly hovers in the world of Tagore’s verses and this awe is dissipated through the book itself.

In chapters like Jaage Sorosh Sangeetomodhurima, Mainak bravely critiques the bard with utmost reverence. It is almost like a parley at a ‘poet’s meet’ where one dares to ask a poet if he loved writing what he did! However, he reasserts how every verse need not hold an esemplastic significance and yet can reach out to a reader with an aesthetic delight that one closets in the locker of the heart. Pain, pathos, migration, gratitude, love and virtues alike find space in myriad chapters of the book and are scrutinized through the lens of Tagore. Mainak seamlessly enmeshes the prelude of one song with the interlude of another to create an engaging interplay of contexts.

As he rightly points out in his chapter titled Sonyasi Je Jagilo, Tagore keeps morphing himself in many avatars: his love for nature and love for Man blends with his love for the Almighty through his verses. The pagan, the religious and the humane all blend in the prophetic enlightenment that Mainak unravels through his book. As the Chapter E Khela Khelabe highlights, the word ‘khela’ has implications in Bengali that range from being a child’s play to a game of beguilement, from Shree Krishna’s ‘leela’ to a refuting ‘chhelekhela’: Tagore, in his manifold verses highlight this play. Mainak interesting engages himself in a play with the poet himself, a hide – and – seek of signifiers that remain purloined till Mainak identifies, and the reader realizes its inevitability. Mainak’s play weaves a multi-dimensionality to this illusion and brings Tagore out of linearity as the QR codes leading us to the songs of Dr. Tanya Das complement the discussions.

The book is an enlightenment and Mainak remains the Lucifer holding the beacon that darts a shaft to the verses of Tagore from an angle very relatable yet untraversed. Publishers like Penprints Publication deserve a laudable appreciation for venturing out to endorse such experimentations that juxtapose tradition with individual talent, as Eliot would say. The text would surely remain an archival piece in research, criticism and discussion on Tagore in years to come.

*

Add comment